Oki Sato, founder of the exponentially prolific Japanese studio Nendo, just can’t stop making things.

“I’m a workaholic,” says Oki Sato, principal of the Tokyo-based studio Nendo. “I just keep designing things.”

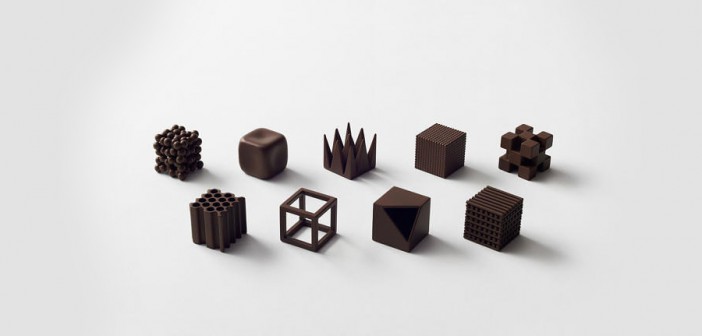

Workaholic might be an understatement considering the tremendous output of Sato and his team of 25 designers and 6 project managers. It’s only May and so far this year Nendo has released 50 metal chairs inspired by comic books; 12 shape-shifting cabinets; a series of wire-frame lights for the New York gallery Friedman Benda; a trio of side tables for the Italian brand Cappellini; about a dozen marble furniture pieces and accessories for Marsotto Edizioni; lucite rocking horses for Kartell; interiors for the Tokyo department store Seibu; branding, a showroom, and products for the door company Abe Kogyo; chocolate bars; packaging for a craft beer company; tote bags; pillows; notebooks; pet products; and candles.

For Sato, creating things and coming up with clever solutions just makes him happy.

“It has to be done in a very fun way,” he says. “That’s something that a lot of designers forget about, enjoying the process. When we don’t enjoy designing things, people won’t enjoy them when they’re done. I just work a lot and enjoy the process. If there is any secret, that’s the only thing!”

But that’s not the full story. His scale and reach go well beyond the 30 or so people employed at his studio, thanks in part to a network of corporate partnerships and ventures that allow him to work on hundreds of projects at once.

A FORTUITOUS MENTORSHIP

Sato’s typical process starts by talking with clients about their problem. As much as possible he tries to design the brief alongside the clients and discuss whether or not they really need the project. If it progresses, Sato goes to his studio and begins sketching potential solutions. When he hits on the strongest concept, he then finds a designer in his studio and hands off the idea for it to be developed further. They make 3-D printed physical mock-ups, talk about and refine the design, then decide on the final direction.

A Torontonian who moved to Japan when he was 11, 38-year-old Sato started Nendo in 2002 with a few friends right after graduating from architecture school. (The name translates to modeling clay in Japanese.) After visiting Milan Design Week—an annual furniture fair and citywide design celebration—Sato became enamored with design and decided that he wanted to pursue that as a profession. During its early years, Nendo worked steadily, creating a portfolio that was just as diverse as it is today.

In 2007, Nendo had a turning point of sorts after collaborating with revered Japanese fashion designer Issey Miyake. Eager to find a way to reuse reams of paper that were a byproduct of his fabric-pleating technique, Miyake invited Sato to think about how to make a product with the material. “I would meet him every week and show him prototypes, and he taught me a lot of things about design,” Sato says. The result, the Cabbage chair, was an instant hit. Composed of layer after layer of paper coated in a resin, the design starts off as a cylinder but turns into a seat after peeling back the individual sheets.

Miyake’s mentorship was an inspiring crash course in product design for Sato. His work embodies logic and levity in equal measure, a byproduct of his formal architectural training and personal obsession with design. Despite working with one of the most revered fashion designers in the world (the chair went on to become part of the design canon, thanks to a MoMA acquisition), Sato doesn’t attribute his present-day success—and downright design celebrity—to one specific moment. Rather, it’s been a slow burn.

“I don’t think we had a big break,” Sato says. “In Japan it’s interesting. People compare me to Major League Baseball because a lot of players do very well and are superstars in Japan and then they go [directly]to the major leagues. In my case, I wasn’t well known in Japan. I was like a high school student going to the States, starting from the minor leagues, stepping up day by day and finally coming to the major leagues. That’s something very new in Japan.”

THE BUSINESS OF NENDO

Sato has certainly achieved Ichiro status at home and abroad as companies have been courting him and his firm for collaborations. While some American industrial design consultancies have been stagnating, business is healthy at Nendo. In the United States, companies have been scooping up design consultancies to bolster in-house design teams. In Japan, the opposite is true.

“The companies are noticing that by locking [designers] in, the designers lose their creativity, in a way, and the company loses its creativity as well, so a lot of huge companies are asking Nendo to make a joint venture,” Sato says noting that within the next year he’ll probably launch seven or eight companies in the Nendo orbit. “It’s a way of training, a way of consulting, a new way of collaborating—a way of opening the door. It’s not about just about having the know-how of a single small company, but it’s about opening up and sharing these ideas and the techniques we’ve learned in the last 14 years. That’s very important for Japanese design.”

The ventures are stand-alone companies that usually have between 20 or 30 people from the larger brand. They collaborate with Nendo‘s designers on projects and learn how to work like the firm does. Then they go back and forth between the venture and the bigger company. Philosophically, Sato believes in sharing knowledge, and it works both ways for his firm. One of the most recent ventures was with an interior construction company that has more than 300 employees. When Nendo needs to work on a larger project—right now it’s doing more interiors projects and has a mall opening in Bangkok in the next few weeks—it can call upon its team. Sato is in the process of starting ventures with a television network, a newspaper company, and a product design and branding firm. “It’s like mushrooms growing,” he says.

A SINGULAR VISION

Despite having so many burners going, Sato is able to maintain a consistent vision, thanks in part to the way he thinks. No matter if it’s collaborating with designers within Nendo or outside of the company, it’s all the same to Sato. “I try to have my ideas as simple as possible so that everyone understands them,” he says. “Whether we have an understanding or if we haven’t know each other for a long time, when we come with a striking and single idea, we can share that in a second. That’s the most important part of my job.”

Sato describes the irreverent, delightful moments in his pieces as exclamation points—details that make a person feel “!” He arrives at the idea by looking not at the object he’s trying to create, but beyond it. The Design Museum Holon is staging a retrospective of Nendo‘s work—the studio’s first ever—titled “The Space In Between,” which focuses on this approach.

Sato seems a bit reluctant to reminisce about the studio’s body of work when I ask about personal insights he’s gleaned from working on the exhibition and assessing the hundreds of things he’s made. “I try not to look at the past because I’m working on close to 400 projects at the moment,” he says. “That doesn’t leave me time to think about the future or the past since I’m working on the now.”

All Images: courtesy Nendo