AMONG THE SPENDING choices for governments of poorer nations, kick-starting the technological revolution may at first seem like a low priority. Compared with critical infrastructure, healthcare, or schools, improved digital access and less waiting times for birth certificates feel like luxuries that should come further down the road, or perhaps be left to private enterprise. But there is reason to rethink this.

Fast economic growth is the best way to reduce poverty. A recent Tufts University study found that digitization is one of the biggest drivers of a nation’s economic success. The report argues that that economic growth is mostly achieved by careful policy-setting—in other words, it’s best driven by government.

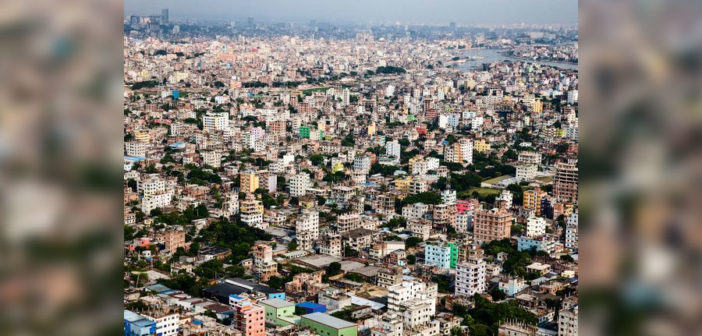

Of 60 countries the report measured, Bangladesh received the lowest score for its digital technologies. But the south Asian nation has no intention of staying in last place: It is in eighth place in the world for the pace of its technological advancement. That’s because of an ambitious approach to the digital economy.

This month, I presented findings from a major analysis of Bangladesh policy options to Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina at a United Nations leaders’ conference in New York. The project was a collaboration between my think tank, the Copenhagen Consensus Center, and the world’s largest NGO, the international development organization BRAC. We engaged dozens of teams of economists to research the costs and benefits of 76 responses to the nation’s key challenges, covering everything from stepping up immunization to building a better transportation network. We asked a panel of eminent Bangladeshi thought leaders and a Nobel Laureate economist to rank all of these proposals.

Alongside many more traditional investments, the panel found some digital economy policies that would be transformative.

The Bangladeshi government spends more than $9 billion on public procurement every year. Its outdated process is slow, opaque, and open to corruption. This causes high prices, long delays, and inefficiencies. Among the top priorities recommended for Bangladesh, our panel urged a government-wide roll-out of e-procurement (using online systems for the government purchase of services and supplies), which the government has tried with one agency.

In the pilot, competition skyrocketed and prices dropped by more than 10 percent. Our research estimates that government-wide digital procurement would reduce corruption by 12 percent, and save around $670 million annually—about enough to pay for Bangladesh’s road-system spending each and every year. Each dollar would generate returns worth $600.

Another top proposed solution was reform of the antiquated and complex land records system, which is a time-consuming, slow, and potentially litigious paper-based process. Instead of using the Bangladeshi government system, many citizens just rely on informal titles and deeds. For one land registry service, the economists found that digitization would reduce costs by more than 90 percent and require just two visits to government offices rather than five. This would provide more secure property rights, which are closely linked to higher economic growth.

Meanwhile, the Copenhagen Consensus recently conducted a similar research project in Haiti, funded by the Canadian government. As in Bangladesh, we worked with local and international researchers to examine policies that would reduce poverty, improve health and education standards, and speed growth in the poorest nation in the western hemisphere.

And again, two digital economy policies were among the top-ten recommendations (which included reforming the electricity sector, fighting child malnutrition and boosting early childhood education access) identified by a panel of eminent Haitian economists and a Nobel laureate.

Internet coverage in Haiti remains limited and expensive. Just 4 percent of households have access, and fewer than 1 percent of Haitians have mobile internet. Our researchers found that increasing mobile broadband penetration to 50 percent over 5 years and installing an undersea cable to support the increased traffic would stimulate economic growth and reap benefits worth more than 12 times the costs.

Another smart investment would be digitizing processes at Haiti’s largest port. The nation has enormous maritime potential, with more than 1,500 kilometers of coastline, but is among the Caribbean countries that exploit their marine resources the least. A computer system dedicated to the port, allowing customs administration to exchange data and messages confidentially and securely, would increase productivity and revenue and decrease smuggling. The benefits are worth nearly 7 times the investment.

What can be learned from these findings for Bangladesh and Haiti? First, that even for countries at the bottom of the ladder, digital economy solutions are worth investigating, even along with projects addressing more life-and-death concerns. And second, that investment in digital services can prove comparatively inexpensive because once the systems are in place, the costs of adding users are close to zero. For example, when you have a computer in each village (a “digital center”) with the birth certificate program installed, extra birth certificates cost almost zero. And adding more apps to the computer, allowing for help with migration or land digitization adds little cost, too.

Digital policies can help citizens by making interactions with the state easier, cheaper, and less corrupt. They help the whole country by making everyone more productive. It is likely that most nations, just like Haiti and Bangladesh, have smart digitization opportunities waiting to get implemented, where a little money can generate a big push forward.

–

This article first appeared in www.wired.com

Seeking to build and grow your brand using the force of consumer insight, strategic foresight, creative disruption and technology prowess? Talk to us at +9714 3867728 or mail: info@groupisd.com or visit www.groupisd.com