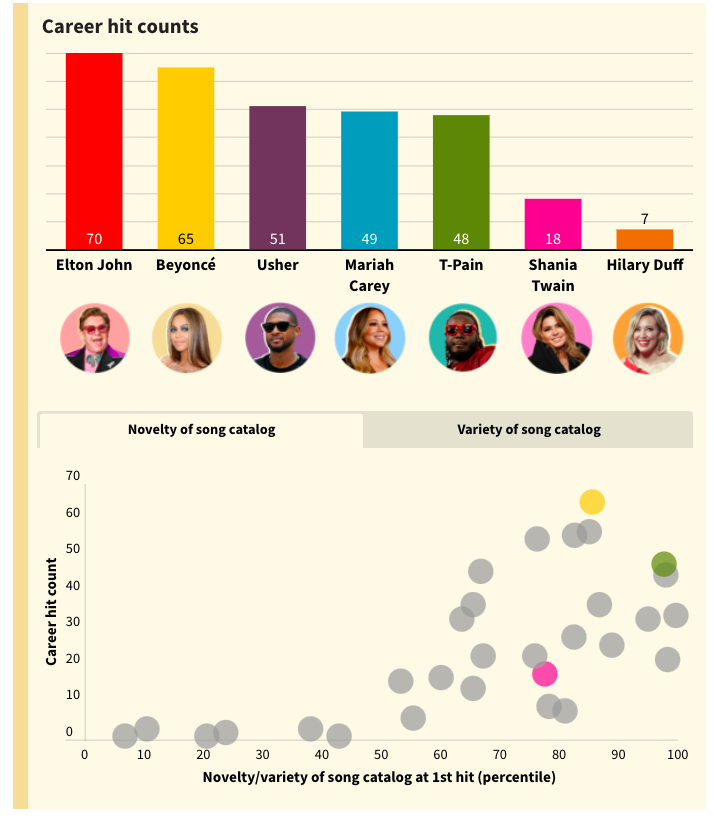

Why has Beyoncé had over 60 hit singles since 2003, while Hilary Duff, who debuted on the charts in the same year, has only had seven? How do we account for the enduring catalogs of Billy Joel and U2 while Lou Bega’s and Blind Melon’s stars quickly fizzled? And, why, for every Stevie Wonder or Dolly Parton, are there dozens of Tommy Tutones and Chumbawambas — acts that score a hit or two and then all but disappear?

“Music has a very high churn rate, making it a quintessential creative industry,” says Justin Berg, an assistant professor of organizational behavior at Stanford Graduate School of Business. “It is full of one-hit wonders, but we see very few sustained hitmakers.”

A search for what causes this divergence lies at the heart of new researchopen in new window by Berg, who has long studied the workings of creativity. He finds that a musician’s portfolio of songs leading up to their initial success helps predict how well their career will endure. Artists who have crafted a creative catalog of music by the time they achieve their first hit tend to keep generating additional hits. Those with less creative catalogs early in their careers often peak quickly, then fade away.

This insight is a departure from existing theories about creativity, which assume that the process of creation is “path independent” — the success of one creative work is unrelated to the success (or failure) of the next one.

“I instead explored the possibility that creative endeavors are path dependent: Early work is connected to later work, and success can mess with you — it can lock you in, it can make you learn things you shouldn’t have or prevent you from learning as you go forward,” Berg says. “It can create expectations that are unrealistic or limiting.”

The Double-Edged Sword of Creativity

To test this idea, Berg assembled an archival dataset of more than 3 million songs by nearly 70,000 artists — virtually every song released by any artist on a hit-producing label between 1959 and 2010. “It was a giant effort, but well worth it,” he says of the data collection process.

From this list, Berg tagged artists with at least one Billboard Hot 100 song during the period, amounting to 7% of the total population of artists (who altogether produced 19,000 hit songs). He then measured the level of creativity in each artist’s portfolio of songs at the time of their first hit. Using a series of algorithms, Berg quantified creativity in terms of both novelty and variety: How sonically distinct was the artist’s portfolio compared to others’ hits at the time? How internally diverse was the artist’s catalog of songs? These two measures of creativity were then overlaid on each artist’s career to determine whether a relationship exists between a portfolio’s creativity and long-term success.Quote“Artists cannot maximize their odds of being a hitmaker without simultaneously increasing their odds of having zero hits in their careers.”

Berg found, most fundamentally, that artists with novel or varied catalogs at the time of their first hit were more likely to keep creating hit songs. Two mechanisms likely drive this result. First, expectations: Because success often occurs quickly in creative industries, musicians can be thrust from obscurity to icon status in weeks. Industry gatekeepers and fans then exert tremendous pressure, through their expectations, on the kinds of music with which the artist can find success going forward. Having a more creative portfolio when initial success strikes broadens the range of these expectations, and thus the possibility of longevity in an ever-shifting market.

The second mechanism is learning: A novel or diverse portfolio also implies that the artist has been experimenting and learning a range of creative tools. Once they achieve success, this past learning can serve them well as they try to keep up with the constant changes in pop trends. Artists who reach their initial hits with little creativity in their portfolios usually struggle to adapt as the market leaves them behind.

“When you go from a low level of success to being pumped through the airwaves all over the world, then everything you’ve learned up until that point becomes very important, as do the expectations of the gatekeepers and the audience,” Berg says. “At that point, artists are much more likely to succeed with new songs that are closely related to their existing portfolios. The problem is they also need to keep up with new trends that emerge in the market. Artists with more creative portfolios have more options for pulling off this balancing act over time, increasing their odds of sustained success.”

However, Berg also found that building a novel portfolio makes it less likely that an artist will have a hit in the first place. Unorthodox music is, by definition, usually not popular. There is an irresolvable tension between cultivating a typical catalog that is likely to have initial success and building a novel repertoire that supports long-term success. “Artists cannot maximize their odds of being a hitmaker without simultaneously increasing their odds of having zero hits in their careers,” Berg says.

Can You “Moneyball” Pop Hits?

Broadly, Berg hopes this research will spark people across all creative industries — from writers and chefs to architects and choreographers — to consider their body of work as a unified whole, akin to an investment portfolio. The novelty or variety of earlier work may enable or constrain one’s creative capacity and success down the road. Taking time to establish a strong foundation may delay initial success but boost the odds of a viable career in the long run.

This study also has important implications for the use of data to predict commercial success in creative work, especially the music industry. Berg suspects that data analytics could help upend the way the music industry chews up and spits out artists.

“Some clever executives or producers could probably take the insights and methods from this study and come up with a data-driven approach to signing and managing artists, where they are preparing artists for sustained success instead of cashing in on short-term opportunism,” Berg says. “If you want to be Bruce Springsteen and eventually sell your catalog for $500 million, then you need more than a couple of hits.”

However, Berg warns that relying solely on quantitative data to predict creators’ success may be misguided. “I think measures like those in this study ought to be used in conjunction with more intuitive assessments of creative work,” he says. “A 100%-data approach may someday beat a mix, but we’re not there yet. At this point, if someone were using a hybrid data and intuition approach, I’d bet on them over either one alone.”

. . .

This article first appeared in www.gsb.stanford.edu

Seeking to build and grow your brand using the force of consumer insight, strategic foresight, creative disruption and technology prowess? Talk to us at +971 50 6254340 or engage@groupisd.com or visit www.groupisd.com/story