Triarchy swapped plastic for rubber to make its new stretch jeans. That’s good news for the environment.

Since Levi Strauss patented the denim jean 150 years ago, the pant has become the world’s favorite garment. At any given moment, half of the world’s population is wearing a pair. But what most people don’t realize is that jeans are full of plastic.

Strauss originally designed jeans as workwear for miners and farmers, so he made them out of a virtually indestructible, stiff cotton canvas. But about 20 years ago, consumers wanted more comfortable and tighter-fitting pants, so brands began making them from softer, stretchier material—which means weaving synthetic fibers, like spandex and polyester, into the fabric.

Of course, the problem with all plastic-based fibers is that they shed microplastics, tiny particles of plastic that get washed into the ocean and end up in our food chain. And at the end of their life, they will not biodegrade, but sit in our landfills for hundreds of years. [Photo: Triarchy]

[Photo: Triarchy]

But what if we could create comfy denim without all the plastic? A denim label called Triarchy is on a mission to do just that. The company has worked with its mill in Italy to develop a fiber from rubber that can be used to create the same kind of stretchy texture we’ve become used to, but that will biodegrade at the end of its life. [Photo: Triarchy]

[Photo: Triarchy]

Adam Taubenfligel cofounded Triarchy with his brother and sister 13 years ago, and as they built their supply chain, it was obvious how terrible denim manufacturing is for the planet. “It’s an abhorrent product,” he says. “It’s everything from the water consumption to irresponsible fibers, chemical use, and plastics. We decided that if we were going to continue this brand, we would have to find a better way to make jeans.”

Over the past decade, many other brands have been on a similar quest to improve the way jeans are made. The Ellen MacArthur Foundation, which advocates for a circular economy, launched a project called The Jeans Redesign in 2019, where it enlisted brands ranging like American Eagle, Gap, H&M, Chloe, and Frame to rethink many parts of the denim-manufacturing process. This included eliminating chemicals from the manufacturing process and designing jeans that can be easily recycled by making hardware easily removable.

Taubenfligel has worked to reduce Triarchy’s environmental impact in his own way, including exclusively using organic cotton, distressing jeans with lasers rather than chemicals, and reducing water consumption. But from the start, he was eager to cut down on plastic use. At first, the brand just didn’t use any stretch fibers at all, which made for stiff, rigid jeans. “That was okay for fashion denim and looser fits,” he says. “But you have to be committed to that look, which isn’t something that you can scale across all consumers.” [Photo: Triarchy]

[Photo: Triarchy]

Some mills began offering denim with recycled plastic fibers, from water bottles. But Taubenfligel wasn’t sure that was such a good idea, partly because mills often have to include chemical additives into the recycled fiber to make it more durable. And recycled plastic has many of the same problems as virgin plastic, including shedding microplastics and the fact that it is not biodegradable.

Eventually, however, Taubenfligel began having conversations with Alberto Candiani, the fourth generation owner of the Candiani Mill in Italy, which is known for its luxury denim materials. Together, they discussed how they could create stretch denim with a biodegradable fiber. An obvious answer was rubber, a material that comes from the rubber tree that has some similar properties to plastic. But they couldn’t find any denim fabric on the market that used rubber. So they decided to work together to create it.

It’s curious that rubber hasn’t been used more as a natural replacement for plastic fibers, especially as consumers have become more aware of how damaging plastic is to the environment. Part of the problem is that while scientists can engineer plastic in a lab to give it whatever properties they are looking for, rubber is a natural material, which makes it harder to manipulate. This is something that Candiani and Taubenfligel discovered as they embarked on the process of creating this rubber-infused fabric.

[Photo: Triarchy]

[Photo: Triarchy]

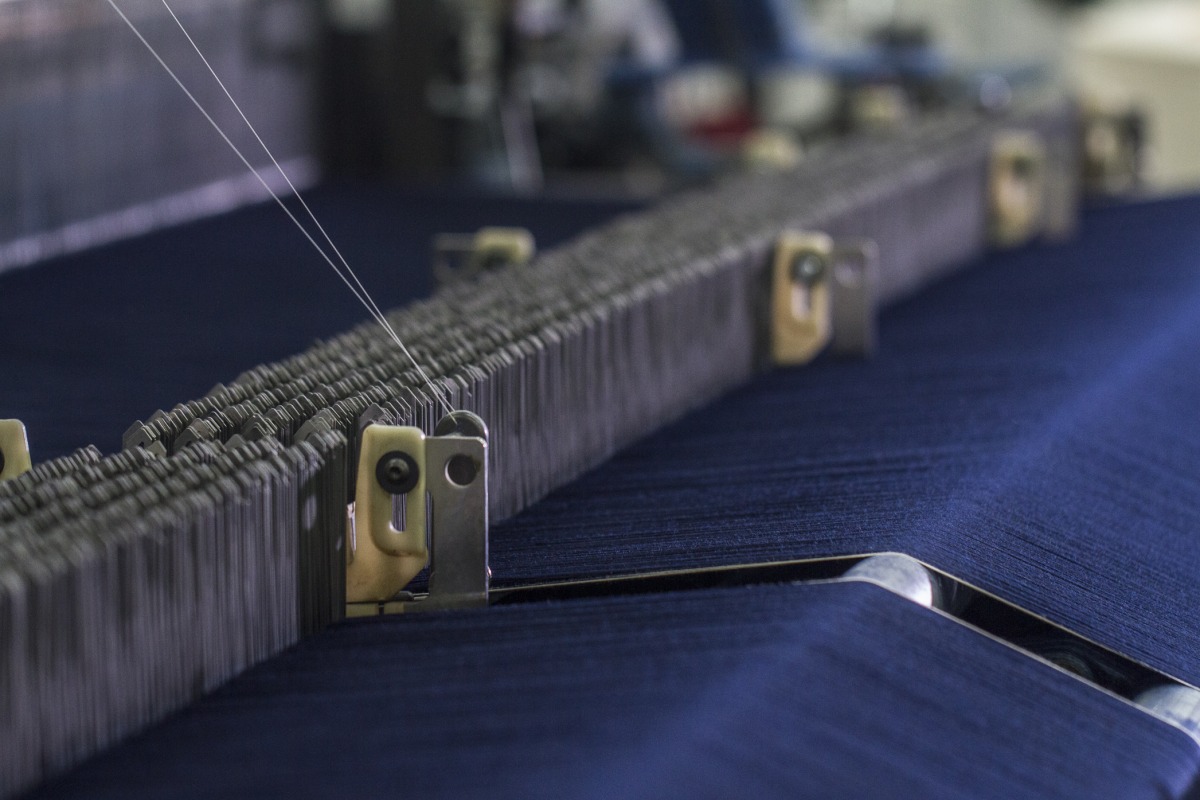

In stretch denim, each strand of cotton—which is as thin as a strand of hair—is wrapped with plastic fibers. So Candiani’s goal was to create a rubber fiber that had similar properties to plastic, and could be wrapped around cotton in a similar way. The mill explored lots of different rubber fibers, testing them out one by one, to see if they could weave a fabric that seemed akin to the kind of stretch denim that consumers are used to. Some came out too stiff, others didn’t bounce back to its original shape after it was stretched. “The scientists in the mill’s lab kept manipulating the rubber, testing out its different properties,” Taubenfligel says.

The first prototype of the material was very high in stretch, but Taubenfligel wasn’t keen on it. “It was the kind of fabric you would find in jeggings,” he says. “That wasn’t ideal because it doesn’t tend to work on other styles. I wanted to be able to drape the fabric, so we could use it on wide legs and jackets, as well as slimmer styles.”

Eventually, they landed on a material that worked. The jeans look and feel like the kind of stretch denim consumers are used to wearing; they’re soft and stretchy, conforming to the body much like athleisure. But there are significant differences. According to third-party testing, they biodegrade in two years, and will fertilize the soil while doing so. And they also discovered that while plastic fibers tend to trap body heat, which can make you feel clammy, rubber has cooling properties.

Triarchy has exclusive rights to this material till the end of next year, but then, Taubenfligel hopes other brands will start using it. For one thing, it is now very expensive to produce this material, since it is so new. If Candiani can scale up its operations, it can reduce the manufacturing costs. But more importantly, this material could be a relatively easy way to get a lot of plastic out of landfills. “It’s no use if only one brand is using it,” says Taubenfligel. “But if it becomes widespread, it has the potential to change the industry.”

—

This article first appeared on www.cmocouncil.org

Seeking to build and grow your brand using the force of consumer insight, strategic foresight, creative disruption and technology prowess? Talk to us at +971 50 6254340 or engage@groupisd.com or visit www.groupisd.com/story