They don’t just generate results. They produce breakthroughs.

Lynda Rae Harris was in her 20s and the owner of a Los Angeles–based ad agency when she met her second husband, Stewart Resnick. He was an entrepreneur who had built a successful janitorial business from scratch after his father won an industrial floor scrubber in a contest. Together, the Resnicks made their first joint acquisition—the floral wire service company Teleflora—in 1979. They followed it with acquisitions of agricultural land in California and of the Franklin Mint, all chosen because of Stewart’s penchant for service businesses with repeat customers.

But even the most loyal customers need a reason to keep coming back, and Lynda was always looking for new ways to draw them in—seeing and creating what they needed long before they knew they needed it. For example, she came up with the “gift within a gift” concept of packaging Teleflora flower deliveries in a reusable planter or vase. Lynda also redesigned the Franklin Mint’s traditional product set of commemorative coins and stamps to include collectible dolls, including porcelain Scarlett O’Hara and Princess Diana dolls that earned millions.

To make the most of their agricultural assets, Lynda sold the masses on a then relatively unknown fruit, the pomegranate, by packaging it as an antioxidant-rich juice drink now known as POM Wonderful. She also rebranded clementines—a sweet orange–mandarin orange hybrid—as “Cuties” and marketed them to time-strapped parents with the slogan “Peel It Yourself.”

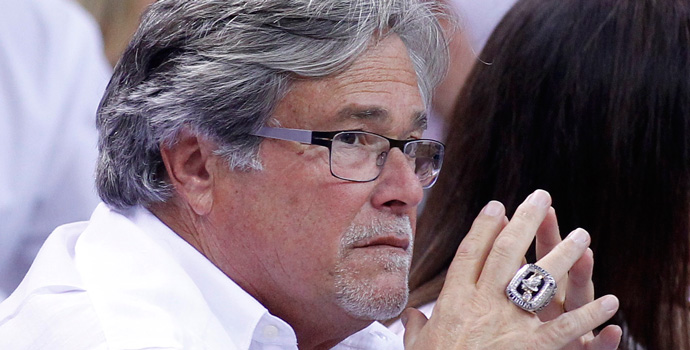

Stewart and Lynda Rae Resnick, owners of Teleflora, Franklin Mint, POM Wonderful, and more Photograph by Stefanie Keenan/Getty Images for LACMA

Stewart has an eye for purchasing viable businesses with high financial potential. He knows how to make them perform. Lynda can transcend their perceived limits with innovative product ideas and focused marketing. She knows how to produce entirely new business lines, time and again. Together, their ability to perform and produce has made the Resnicks billionaires.

Billions without Silicon

Growing a business from nothing to a billion dollars in value within 25 years is an incredible feat. Lynda and Stewart Resnick achieved that mark not through some technological breakthrough, but by exploiting decidedly untrendy businesses, including the commodity business of agricultural fruit packing. They did it all without worrying about any of the common refrains associated with dramatic success: mastering the speed of change, managing the relentless push of digital, or seeking out rapidly growing markets.

Yet the Resnicks are not unique. There are about 800 self-made billionaires in the world today. (They represent about two-thirds of the total; the rest inherited their billions from either parents or spouses.) The total wealth held by self-made billionaires currently constitutes about US$5 trillion, or roughly 7 percent of the total global gross domestic product. This represents more than a threefold increase since 1987.

The rapid pace of change today seems to favor people who become self-made billionaires. Indeed, it was our research into business disruption that drew our attention to self-made billionaires in the first place. Here was a group of people who had not just managed dramatic change, but apparently thrived on it. What do they do that is different? What do they know that others do not? How do they overcome the challenges that seem to overwhelm other business leaders?

To answer those questions, we set up a research team to look at the 2012 Forbes list of the world’s billionaires and identify those who were self-made. From that group, we randomly selected 120 people, adjusted the list to mirror the geographic and industry distribution of the larger sample, and set out to learn as much as we could about them. We also interviewed 16 individuals from this list in depth. These 16 are representative of the overall population of self-made billionaires, at least where it counts most: in their approach to business success.

We expected our results to confirm some basic assumptions about highly successful entrepreneurs. We believed self-made billionaires as a group would look a lot like Mark Zuckerberg or Jeff Bezos: people who create value through their deep understanding of highly innovative, fast-moving technology sectors such as social media and Internet commerce. But we found that the majority of self-made billionaires look on the surface a lot more like Lynda and Stewart Resnick. They tend to be serial entrepreneurs; many of them don’t really become wealthy until they start their second, third, or fourth business in an established market, often when they are in their 30s or 40s. They then grow it progressively over years—even decades—to create more than a billion dollars in value.

Self-made billionaires are different from the average business leader in one respect: the way they look at the world. Their unusual perspective allows them to turn good ideas into great businesses. We found that most self-made billionaires practice five habits of mind —ways of thinking and acting that generate uncommonly effective ideas and approaches to leadership. These five habits can be summed up with the word produce. To produce, in our lexicon, is to look beyond an existing business or market to envision something new, develop the often divergent resources necessary to make it real, and sell it to customers who didn’t even know they wanted it. Producers see unmet demand or potential for disruption and meet it head-on. They do this not once or twice, but throughout their careers. If they suffer professionally, it’s because producing is difficult to measure, and sometimes difficult to spot.

Producers are one prevalent type of professional talent. The other prevalent type could be called performers, because of the way their success is tracked: through performance. Performers are the hugely talented people who manage, optimize, and improve human endeavor within established guidelines. This bias toward performance exists in almost all institutions, and it affects people’s lives practically from birth. Academic performers get the awards and scholarships, sports performers get the wins, political performers get the votes, and corporate performers get the returns and results. They all get the promotions and accolades.

At least 25% of self-made billionaires were fired from established companies early in their careers.

Anyone who succeeds in business must have some ability as a performer. But many successful professionals also have some producer talent. You might have some active producers already working for you. You might even be one yourself. But are you—or is your organization—making the most of them? Given the right context and encouragement, the producers in your organization might apply their habits of mind to conceive and create billion-dollar businesses. But if history is any guide, the context of a typical business organization rarely enables this kind of producing to occur—at least not to the extent you need.

Consider this: At least 25 percent of self-made billionaires were fired from established companies early in their careers. Many others resigned from companies in their field of choice, typically out of frustration because the company moved too slowly, or was too antagonistic to their ideas, or simply bored them. The experience of these entrepreneurs reflects an unfortunate reality: Companies are set up to perform. They are not set up to produce. If firms were more capable at producing, they would not have to worry about combating disruption from outside. They would already be skilled at redesigning, disrupting, and innovating from within.

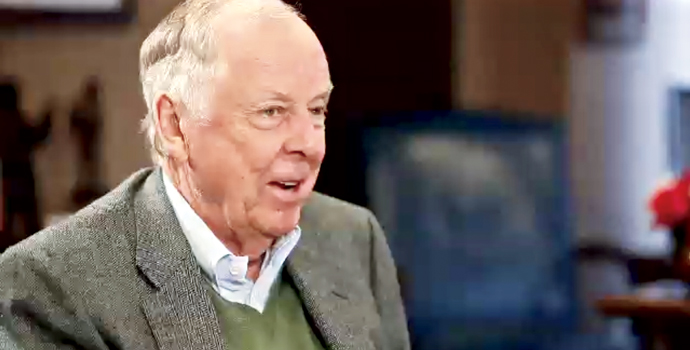

Boone Pickens, oil and gas magnate. Photograph by PwC

The self-made billionaires who started their rise to fortune after leaving established companies represent only a small share of the value that is lost when businesses favor performing too much over producing. There are only a few hundred self-made billionaires who left companies like Phillips Petroleum (oil and gas magnate T. Boone Pickens), British Telecom (Celtel founder Mo Ibrahim), Redken (Paul Mitchell co-founder John Paul DeJoria), PepsiCo (AOL founder Steve Case), Blendax (Red Bull founder Dietrich Mateschitz), and Salomon Brothers (Michael Bloomberg, founder of the company that bears his name). How many hundreds of thousands of people with producing talent exist in the business world, their talent largely untapped, simply because they have to focus on performing in order to succeed?

Having performers in the organization is not a bad thing. Performance is critical to success. But an exclusive focus on performing makes it hard to see and create new value. If you care about building new businesses, and not just about maintaining and expanding your old ones, then you need to make the most of the producers you have. You also need to know how to find more of them if you don’t have enough.

Habits of the Producing Mind

As a rule, large organizations do a poor job of distinguishing between high-profile roles that require a top professional skilled at optimizing a known space (a performer) and roles that require one skilled at redefining or disrupting that space (a producer). If your company is performer-centric, all successful activity looks like performance, and all roles look like performers’ roles. You may be wasting your best producers in jobs better suited to performers.

Even if you recognize that you have a role that needs a new, innovative approach, how can you identify employees who have the producer abilities to handle it? Step one is to understand and recognize the five habits of mind that producers share.

-

Ideas: Empathetic Imagination

Lynda and Stewart Resnick had owned 130 acres of pomegranate trees in California’s Central Valley for 10 years before Lynda learned of the fruit’s antioxidant power. It was 2002, and she quickly saw how to position pomegranates prominently to meet the health and wellness trend taking hold in the United States. Unfortunately, a person would need to eat more than two pomegranates every day to get a significant benefit. Juice was a more efficient delivery mechanism. Armed with this idea, Lynda set up a team to figure out how to juice pomegranates en masse. She then designed a bottle distinctively shaped like two stacked pomegranates. Five years after the launch, POM Wonderful reached $165 million in annual sales.

In almost all stories of self-made billionaire success, there is a similar blockbuster idea, conceived with a similar formula: awareness, empathy, imagination, and knowledge. The producer has typically worked in the field long enough to have an awareness of critical trends, especially those just emerging (like the antioxidant fashion in the early 2000s). He or she sees an underexploited customer need, and experiences deep empathy for those customers. The producer then uses imagination and knowledge to convert that empathy into a business idea with broad potential. Paradoxically, the producer may have had to spend years as a performer, working in the market, to get that knowledge. Then he or she will need to use imagination to forget everything that was learned as a performer, to see the opportunity in a fresh way.

Lynda Resnick alluded to this mix of experience and insight when she discussed her facility with the great idea. “You might think that it’s divine intervention, because that’s the way I feel sometimes,” she said, “but it’s also the sum total of all these years of experience….Being a great marketer is synonymous with being a great friend. In other words, you have to listen.” She watches television, reads People magazine, and tries to stay plugged into popular culture, if only to see what moves people. “You don’t have to be a genius,” she added. “You have to see what people are watching. You have to listen to conversations. You have to pay attention. For God’s sake, you have to pay attention.”

Another producer with a facility for ideas is Judith Faulkner, the founder of Epic Systems—one of the leading vendors of electronic health records systems. She was a graduate student in computer science at the University of Wisconsin–Madison in 1979 when she was recommended by a professor to build a basic health record-keeping system for the university’s psychiatry department. Her performer’s knowledge got her the job in the first place. But it was her talent as a producer—her empathy for patients needing continuity and medical professionals seeking to waste less of their time, along with the imagination required to reconceive standard IT practices—that led her to a groundbreaking idea about improving the quality of medical records.

In retrospect, the idea was remarkably simple, but no one else had applied the experience and imagination needed to see it. “[I] put the patient at the center,” she told an interviewer. “I developed a clinical system at a time when the healthcare world had pretty much only billing and lab systems available.” She has kept careful control over the parameters of the system ever since, even when that made it difficult for other medical records systems to connect to it. She says her customers (physicians and hospitals) need that high level of integration and safety to feel secure enough to entrust their records to her company. In one study conducted by the healthcare research group KLAS, Epic generated an 86.4 percent approval rate among physicians, compared to 75 percent for the next closest system.

Look for a similar level of empathetic imagination among your employees. Who shows insatiable curiosity about the customer? Who has insights about what that customer needs? Who has new, unexpected ideas about products, services, deals, offers? These are your potential producers in action.

-

Time: Patient Urgency

The second habit of mind involves time. The creation of massive value in an industry does not happen overnight. The billion-dollar idea often comes after years, even decades, of commitment to a market space. Skilled producers learn to be patient. They know how to wait for the right idea at the right time. But once they hit on a compelling idea, they have a bias toward action that compels them to take urgent steps. In the producer’s mind, timing is untethered from the quarter-driven mind-set of the typical American corporation.

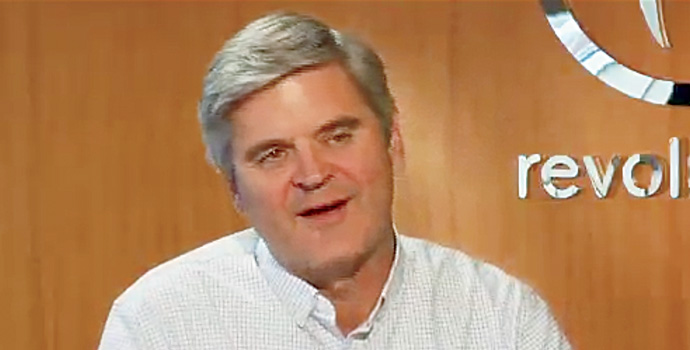

Steve Case, founder of AOL. Photograph by PwC

AOL leader Steve Case understood the balance between patience and urgency. He was part of the team that started AOL in 1985, as a service for inexpensive home computers, and became CEO in 1991. In those early years of the Internet, AOL (originally called Quantum Link, then America Online) was the first access provider designed to be a national service, with a customer-friendly interface that made it easy to get and stay connected. It took until 1996 for the service to become a recognized name. Case and the rest of the AOL leadership spent that time patiently building the infrastructure and relationships needed by a mainstream communications network to handle traffic from a mass market. Since broadband Internet access was not widely available, much of this had to happen through dial-up connections.

“I used to say AOL was an overnight success 10 years in the making,” Case said when we met with him. “By the mid- to late ’90s, when the Internet came into focus, and new people were joining AOL in large numbers, and the brand was on the cover of a magazine, it looked like AOL just kind of popped out of nowhere and was an instant success. But we’d been at it for nearly a decade, trying to fine-tune and get the [computer manufacturers]to include a communications modem instead of viewing it as a peripheral, and get the network costs down so we could charge less for our service, and get the software better so it was friendly or more engaging for a mainstream market, and get the content more interesting. There were a lot of building blocks.”

All of that preparation time did not make Case or AOL immune to the need for urgency. From 1996 through 2000, when it merged with Time Warner, AOL grew rapidly to a user population of 10 million. Case made many opportunistic moves rapidly, including the introduction of new forms of multiplayer role-playing games and the bundling of AOL software with Microsoft Windows. At one point, when AOL changed its payment terms to a flat monthly rate, the phone lines were bombarded with callers, and Case rapidly taped a commercial, featuring himself explaining that they were working day and night to cover the sudden call volume.

In your organization, look for people who match the long-term commitments to certain ideas or markets with a sense of urgency about what they can do today to learn more, test more, or do more to be ready. Those people are likely to be producers.

-

Action: Inventive Execution

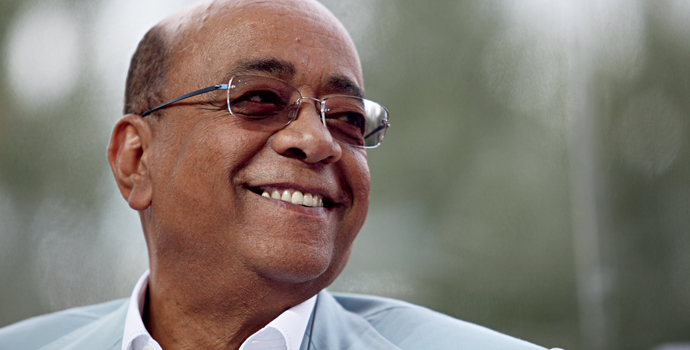

When Sudanese native Mo Ibrahim began buying mobile licenses in Africa to create the telecommunications provider Celtel, he knew he would have to ditch the subscription pricing model that is commonplace in telecom. Subscriptions are designed for people with consistent incomes—a poor fit for most people in sub-Saharan Africa, where poverty is common and incomes are “spiky.” In fact, African governments were having difficulty wooing investors because they couldn’t see how the impoverished population would be able to pay their mobile phone bills.

Mo Ibrahim, founder of Celtel Photograph by Balint Porneczi/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Where others saw Africa’s precarious economics as a barrier, Ibrahim saw an opportunity to change the standard execution model of the industry. He bought licenses for a number of countries and then designed a new revenue structure. His solution? Sell prepaid mobile service scratch cards for a few dollars each. Even people living on a few dollars a day would be able to make the investment. Within five years, Celtel was serving 6 million people in 13 African countries.

We use the word design to refer to the solutions that producers develop as they address the problems in executing on an imaginative idea. Design takes into account multiple factors: the customer experience, the strategy and tactics, the terms of the sale and the deal, the ownership and distribution. In redesigning an existing product, producers will tackle physical look and feel, underlying technology, manufacturing and distribution, pricing, business model, and sales pitch. They will also redesign the ownership and deal structure to fit the opportunity—as Adobe and Microsoft have recently done in converting their application software from a purchase to a subscription model.

This emphasis on design stands out largely because for so many executives, design is taken for granted. The business model, pricing, functions, sales pitch, and deal structure are treated as inherited, predefined by the models, costs, and pricing that already exist in the company and industry. If a company has a design sensibility at all, it applies almost exclusively to the sensory elements we typically associate with the word—the look, feel, or emotions associated with a product. But that’s not true for the billionaires we talked to. They see redesign opportunities everywhere. It’s in the prepaid Celtel card, the parameters for linking to the Epic records system, the shape of the POM Wonderful bottle, and the store layout at Starbucks—a barista places finished drinks on a mini-stage for customers to pick up.

Inside your organization, employees with inventive execution skills will apply their design mind-set to almost everything they do. These producers might ask how they can change the delivery model to increase the potential for scale, or change the pricing to unlock new value, or negotiate a new deal to better exploit the firm’s intellectual property. Those forms of inquiry all involve design, and your company will be better off as a result.

-

Risk: Relative, Not Absolute

When she was 27 years old, Cheung Yan used all her savings—HK$5,000 (US$645)—to start a paper-trading company that supplied pulp to papermakers in mainland China. Five years later, in 1990, she abruptly shut that growing business down and moved to California to start over.

Moving overseas seemed like a huge and foolhardy risk. Cheung spoke only tentative English, she knew no one, her list of local contacts was short, the U.S. waste business was very insular, and she was betting her entire savings—again. But within 10 years, the paper company she founded in California, America Chung Nam, had become the leading paper exporter in the United States. And she was just getting started.

Cheung Yan, founder of American Chung Nam and Nine Dragons Photograph by Philippe Lopez/AFP/Getty Images

You might conclude that Cheung has a large appetite for risk. But actually, the risk would have been greater had she stayed in Hong Kong. Given the limited forests and other wood resources available, she would probably not have been able to keep up with Chinese demand. In North America, she could draw on living forests, emerging tree farms, and reams of recycled office paper. In addition, she would no longer have to deal with the Hong Kong organized crime syndicates, which were reportedly threatening her because she refused to water down her pulp, as they did. These risks were not obvious; if they were, everyone would have moved to California with her. But they were compelling enough to force Cheung’s decision, and she prospered as a result. Later, she added to the prosperity by cofounding a Chinese paper and cardboard manufacturing business called Nine Dragons, which uses the material from America Chung Nam to create cardboard boxes that carry Chinese goods to the United States, where they can be recycled again.

Most self-made billionaires might seem like inveterate risk takers. Kirk Kerkorian, the founder of MGM Resorts International, spent two and a half years during World War II delivering planes to Scotland on behalf of the Royal Canadian Air Force. To fulfill his mission he had to fly across a stretch of the North Atlantic known for such cold and high winds that one in four pilots crashed. But in business, Kerkorian was not a daredevil. Every step he took evolved organically from the one before—from his first business, a charter airline that shuttled vacationers between California and Las Vegas, to his first land acquisitions in Las Vegas, to his development of larger, more ambitious entertainment properties, and then to his role as a shareholder.

Producers, in general, are distinguished not by the level of risk they take, but by their attitude about risk. Most people measure risk in absolute terms: Will this business succeed or fail? Producers view risk in relative terms: Which option presents the greatest opportunity? If the opportunity is right in a risky venture, they’ll look for ways to mitigate risk—as Cheung did by lining up commitments from her Chinese purchasers before she left—but they won’t turn down the venture. It’s a greater risk to lose the opportunity.

For example, Micky Arison, the billionaire owner of Carnival Cruise Lines (currently the world’s largest cruise line), took over the business from his father in 1979. At that time, cruising was a niche vacation option reserved for elderly, wealthy patrons, and Carnival Cruise Lines was a three-ship company growing slowly, one ship at a time. Arison saw, however, that cruise vacations could become a mainstream option affordable for middle-class families. Making his vision a reality required rapid expansion, and a great deal of absolute risk. Not only could the venture fail, but Arison might lose the few ships he started with. Nonetheless, in Arison’s view, the relative risk was much greater if he did nothing. If Carnival didn’t redesign the cruising experience for the mass-market customer, someone else would, cornering the best boats and routes, and ultimately outcompeting Carnival’s established business as well.

When looking for producers, look for people who can credibly judge relative risk. These individuals appreciate the dangers of a new venture, but can also articulate a counterintuitive view: the dangers of not addressing a truly great opportunity.

-

Leadership: Teaming with Performers

More than half of the billionaires in our sample started their businesses as part of a producer–performer team. Lynda and Stewart Resnick represent one obvious example, but there are many others: Steve Jobs (producer) and Steve Wozniak (performer) of Apple; Nike’s Bill Bowerman (producer) and Phil Knight (performer); John Paul Mitchell Systems’ John Paul DeJoria (producer) and Paul Mitchell (performer).

The idea of the solo genius is so pervasive in the way people talk about and think about extraordinary success that it obscures the real story of how good ideas become great businesses. Self-made billionaires are not alone. Producers have the ability to see beyond the parameters of what exists today to imagine new opportunities. Performers, in turn, have the ability to optimize and achieve within known parameters. Value creation requires both.

Inside your organization, look for two employees whose skills seem complementary, and find ways to bring them together on projects. When these pairs occur organically, be aware of the chemistry and promote the two of them together to their next production.

The Producer as Recruit

Some organizations may find, once they start looking for producers, that they have all they need in-house. Others will have to develop, recruit, or acquire producer talent. Start by looking within your company for people whose resumes, backgrounds, or history may suggest a propensity to try something new. Did this person persuade leaders to take a bet on a new product or service, or invest in a partnership that exploits different tools? Did he or she come up with a clever way to get something done—and actually bring it to fruition? (Note, however, that if your candidates have only unrealized ideas and enthusiasm, but no finished product, service, or result, they’re not producers.)

When looking outside your organization, cultivate “catalyst hires”—people recruited specifically for the skills needed to pursue new growth or new capabilities. When recruiting these individuals, frame your interviews to detect people who exhibit the five habits of mind. Have these people shown a long-term commitment to a market or area of expertise? Do they have viable new business ideas for exploiting that market? Do they want to be involved in bringing their ideas to market? How do they describe the risk of pursuing this unproven path? Our experience suggests that the signals are obvious: You generally know when you have a producer in the room.

Your organization may never have enough in-house will or resources to build a broad producer employee base. But you can partner with organizations such as universities, startup firms, and your most creative suppliers. They have producers among their star employees, but growth and rewards may be more constrained without your collaboration. You can also create in-house skunkworks projects and spin them off as new producer-based enterprises. Finally, if you are buying a company, try some producer-oriented due diligence: Look for the potential self-made billionaires, who are probably thinking of leaving—and make sure you give them incentives to stay.

Since embarking on our billionaire research more than three years ago, we have had scores of conversations with executives about the producer habits of mind, and what those habits suggest for established companies seeking new value opportunities. The producer concept has had universal powerful resonance.

But it is one thing to recognize producers and their potential. It is another to take the leap of faith required to give them opportunities, freedom, resources, and attention so that they can produce on your behalf. Producer ideas do not typically have consensus. They are not universally understood, let alone embraced. They might move the company away from its core business. Supporting them is an act of courage. Giving them room to thrive requires deep cultural and infrastructural change.

But if your organization wants to move to a new business successfully, you need the producers who can make that leap. They’re out there, in your organization or nearby, ready with the skills and the will to find and pursue your next breakthrough. Or else to jump to their own enterprise and keep the billions for themselves.

Author Profiles:

- John Sviokla is the head of Global Thought Leadership at PwC (PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP), where he also works with clients on strategy and innovation. In addition, he leads the Exchange, the firm’s think tank.

- Mitch Cohen is a vice chairman at PwC. During his 33 years at the firm, he has served a number of Fortune 500 clients and has held various leadership roles.

- This article is adapted from The Self-Made Billionaire Effect: How Extreme Producers Create Massive Value, by John Sviokla and Mitch Cohen (Portfolio, 2014).

- Also contributing to this article was Laura Starita, managing partner of the communications firm Sona Partners.