Apple Has One Or Two Products, So Why Are They Selling So Many?

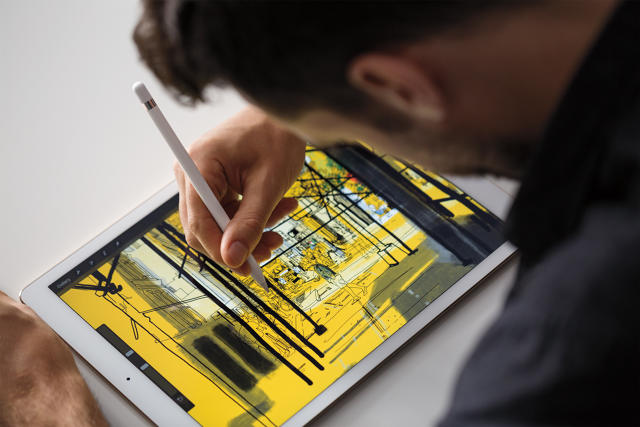

The iPad Pro could have been a big moment for Apple. By adding a keyboard and stylus to a 13-inch iPad, they didn’t just knock off the Microsoft Surface. They physically merged two distinct product lines. At last, their iOS-running touch screens, and their OSX-running computers, were in a single, unified form. Apple’s own industrial designers seemed to be saying, “There need not be a division between poking at an iPad and mousing on a laptop. These things could all be one!”

Except, Apple didn’t take this moment to unify anything. The iPad Pro is still just a big iPad that you can use with some really nice peripherals. It’s, very notably, not a MacBook.

This is what happens when Apple, which has branched into so many seemingly distinct categories, chooses to refine their products rather than integrate them. With the iPhone, Apple turned a laptop into a phone. With iPad, they turned a phone into a tablet. With iPad Pro, they turned the tablet back into a laptop. It’s a technological ouroboros.

These days, there’s an iPad in every color for every occasion; iOS and OSX still live as separate platforms, running their own apps; and the Macbook and iMac lines evolve with half-baked touch controls, but neither touch screen nor stylus support. If I were forced to reverse engineer the logic at play here, it would be that the touching a screen works when you precariously balance a tablet on your desk, but it doesn’t when you sit at a 27-inch iMac with an adjustable neck. Why can I touch some Apple screens and not others? There seems to be no logic grounding these decisions at all.

Atop this confusion, pile on an Apple Watch with a new OS, a new Apple TV that supports apps, and, oh yeah, desktop computers. The Mac Mini and Mac Pro are still around, too.

Most of these products aren’t distinct by any true necessity. They’re all just microprocessors with screens and radio antennas, squeezed into a growingly complex line of physical and cost-analyzed niches where Apple can attempt to shill another product into our lives. But your iPhone has Siri, Wi-Fi, MPEG decoding, and touchpad with infinite button configurations. So why is Apple selling us on an AppleTV rather than broadcasting my iPhone’s content to my TV? (Yes, you’d still need an HDMI dongle, or some sort of integrated AirPlay, or who knows, maybe something else Apple might have invented if their energies were directed at building something other than yet another box.) Your Macbook Air has a 13-inch screen and a keyboard, so why is Apple presuming that screen couldn’t snap off to be an iPad? (And to all the design purists in the world who’d question the taste quotient of these tech-hacks, do you really think that a convertible laptop is any bit less elegant than a tri-folding case that you shape into a triangle to wedge a touch screen at your face?)

Why is Apple making all of this stuff? Why are some products limited from doing obvious, doable things?

Obviously, one answer is simple profit. We all know that Apple makes their money off hard products like the iPad, not services, like Google or Amazon. As Apple grows, selling 100 million of anything isn’t enough to quell the rising expectations of Wall Street. Apple’s strategy in response has been three-fold:

- Quietly buy back their own stock so that, maybe one day, they only need to answer to themselves. (This decision is great!)

- Sell luxury products to China. (Hahaha, you thought that gold Apple Watch was for you?)

- Move more product. You already have an iPhone? Okay, how about a bigger iPhone? What about one with a keyboard? What about one that runs OS X?

Whatever the reason, Apple is expanding their product line to be more complex, rather than integrating their capabilities to become more streamlined. They’re selling us the same core technologies over and over, extruded into various forms that, by the nature of making no earnest attempts at unification, each feel—if only for a moment at the checkout counter—uniquely necessary. “Well, I would appreciate voice control on my television. It would be helpful to track the steps I take every day. How do I do that? Oh, I guess I have to buy this, too.”

It’s also fair to acknowledge that the OS-bifurcated product lines are similar, but not yet feature-for-feature identical. The “mobile” devices are getting faster every year—already good enough for the sort of basic computing needs of 95% of the population—but they’ve yet to reach “good enough,” in both interface and raw power, to fully supplant the desktop hardware and operating system. Yet it’s clear that the delta between what is best in the touch world and what is best in the keyboard-and-mouse world is getting smaller; in many cases, it’s only a matter of preference.

And that preference is really just down to hair-splitting interface at this point: Would you like a bigger screen? A smaller one? How do you want to prompt Siri? Would you like to do it on your wrist, or by talking into a remote control? It’s all feeling frustratingly same-y.

As Dieter Rams put it, “good design is as little design as possible,” and these days, Apple sure is designing a lot of versions of a lot of products. The only real difference between McDonald’s using the same beef patties disguised across multiple burgers and Apple using the same guts disguised across devices is that McDonald’s doesn’t try to sell you a burger for your wrist. Any time Apple boasts about their A9 processor in another product with Siri, we should do a double take. Is this chunk of industrial design born from necessary innovation? Or is this to the same silicon patty sold to us all over again in a new bun?