The sports brand has prioritized style icons at least as much as athletes—and is getting shoes to market quickly.

Stepping out: Last fall, designer Alexander Wang surprised viewers at his New York Fashion Week show with an Adidas Originals collection that included shoes and clothes.

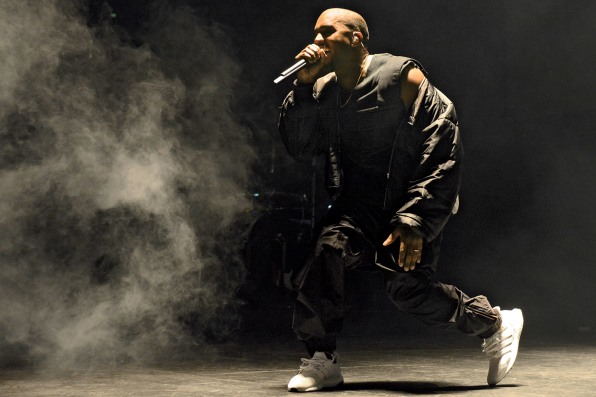

An onyx stage catches fire and three performers, silhouetted in the blaze, begin to sing from behind the flames. You can hear Kanye West’s voice, but you can’t make out his face. The first glimpse of him, poking out of the fire, is a shoe.

But not just any shoe: specifically, a white Adidas Ultra Boost, which until this moment—the Billboard Music Awards in May 2015—has never been worn in public.

West begins his next song and leaps through the flames. He’s dressed all in black except for the two white Ultra Boosts, which hang in the air like exclamation points. “What happens next? Every single store that had [Ultra Boosts] cleared out within the hour,” says Yu-Ming Wu, founder of shoe-culture network Sneaker News, with only a touch of hyperbole.

Never mind that the flames weren’t real, or that, after more than a decade as the second-largest sports brand in the U.S., Adidas had recently fallen behind Under Armour, whose CEO, Kevin Plank, had called the German brand his “dumbest competitor.”

Adidas—with West—had created a moment. Wu compares it to Michael Jordan’s 1988 dunk from the free throw line, which made a legend out of Nike’s Air Jordan III: West’s fiery Ultra Boost debut turned Adidas’s Boost technology into a cultural touchstone.

By fall 2016, Adidas had overtaken Under Armour. The company’s North American revenue soared by 30% from 2015 to 2016, with sales of Ultra Boosts leaping 98%. And while Adidas doesn’t break out many specific numbers, the company credits Ultra Boosts for much of its recent growth. Indeed, the emergence of the line—and Adidas’s ongoing relationship with West (which includes the singer’s Yeezy-branded Boost shoes and apparel)—reflects a strategy that the German sportswear company has been developing for several years, one that relies on celebrities as much as athletes.

With only one-quarter of the American public buying sneakers for their intended athletic use, according to market-research firm NPD Group, Adidas has been turning to cultural influencers as partners, dropping new shoe styles with increasing speed. This spring, fashion designer Alexander Wang released two capsule collections of his AW Run shoes in as many months. Music impresario Pharrell Williams churns out regular iterations on his blocky, Lego-esque NMD line, which sold almost a half-million units online and in stores in a single day in March 2016, with people lining up outside of retail locations from Bangkok to New York. And West has now created six models for the Boost brand. (The NMD and Boost lines have become so popular with sneakerheads that Daishin Sugano, cofounder of the shoe resale app Goat, reports that Adidas climbed from just 10% of his sales to almost 40% in two years.) These kinds of collaborations—along with Adidas’s own in-house efforts—represent a bold departure for the company, which is now treating shoes as fast fashion: stylish, responsive to trends, and engineered to hit the market quickly.

Adidas laid the foundation for its turnaround during a particular low point. Throughout 2013, stores had been ordering less and less merchandise from Adidas’s upcoming seasons, and the company began warning investors quarterly. Shares plunged in August of 2014, and within five months Under Armour had taken the No. 2 spot in the U.S.

Chief marketing officer Eric Liedtke, a 20-plus-year veteran of the company, teamed up with the then-newly promoted global creative director Paul Gaudio in mid-2014 to lead a migration of the creative team from Adidas’s headquarters in the Bavarian town of Herzogenaurach, Germany, to Portland, Oregon—right in Nike’s backyard. While Adidas doesn’t frame it this way explicitly, the company seems to have taken its cue from the market leader. “[The sneaker] industry is born of U.S. culture,” says Gaudio. The U.S., after all, represents 45% of the $55 billion global sneaker market.

Adidas quickly became a transatlantic, co-headquartered brand. Design, advertising, and communications leads were relocated to America, while Germany was tapped to handle materials and manufacturing. “The Americans are better storytellers and, for our industry, have a better aesthetic sense,” Liedtke explains. “The Germans, in broad terms, are very good in engineering, innovations, getting stuff done.”

And that wasn’t the only change. Adidas’s decision-making hierarchy shifted too. In Portland, separate creative silos were established for sports such as football, basketball, and running (again, similar to Nike), allowing teams to develop products tailored to their specific and evolving customers. Both a general manager and a designer sit atop each silo. “If the GMs are driving the car, the creative directors are navigating where to go,” says Liedtke. The groups share core technology, materials, and retail strategy with each other, but with their new autonomy, they’re now able to develop shoes in weeks rather than months.

This speed facilitates the company’s collaborations with outside designers. For more than a decade, Adidas had been exploring creative partnerships with designers such as Yohji Yamamoto and Stella McCartney on high-fashion and fitness lines. But it wasn’t until the company refocused its creative process in the U.S. that it could move with enough speed and authority to make a wider range of collaborations meaningful at scale. Now, Adidas tests the market of a technology—like Ultra Boost—without a celebrity name attached, which takes six months to a year. Then the company brings in a creative partner, such as West, to add a signature touch and make the product line relevant to culture. “Some [sports brands]talk about how hard work equals winning. Some talk about mind over matter,” says Liedtke, in a not-so-veiled nod to Nike and Under Armour campaigns. “We like to talk about imagination—imagining what the future could be.”

Athletes such as the basketball player James Harden and NFL cornerback Marcus Peters remain prominent in Adidas’s marketing. “Everything starts from sport,” says Gaudio. “Without it, we don’t have any lifestyle offerings.” Even so, Adidas’s roster of creative partners is significant, from West and Williams to rapper Pusha T and Belgian fashion designer Kris Van Assche. Williams almost single-handedly brought the company’s 1973 Stan Smith tennis shoe back from retirement when he wore them to the 2015 Grammys and then championed Adidas’s throwback Superstar franchise. His boxy, colorful NMD line is currently Adidas’s most aggressive new look since the Ultra Boosts.

Adidas is also developing a broader creative strategy that goes beyond Portland. This spring, it opened the Brooklyn Farm, a store and creative studio that engages local designers for 10-month-long stints. Gaudio sees the outpost as an opportunity to accelerate product and retail innovation. “It is also about connecting with young creators, startups, students, and influencers,” he says. “It is about getting out of our ivory towers and being on the ground, living and breathing culture and creativity.”

Meanwhile, the company is restructuring again—this time on the manufacturing side. Adidas has already opened an experimental “Speedfactory” in Germany and has a second one planned for Atlanta. The factories treat the shoe as a digital product, deploying new production methods such as motion-capture (to test how new materials respond to movement) and 3D printing. The company plans to produce as many as a million pairs of shoes at Speedfactories by the end of 2018—opening up more potential for creativity, and getting shoes into sneakerheads’ hands even faster.

HAUTE KICKS

Adidas’s creative partners and in-house design team have developed performance sneakers with Instagram-worthy style.

–

This article first appeared in www.fastcodesign.com

Seeking to build and grow your brand using the force of consumer insight, strategic foresight, creative disruption and technology prowess? Talk to us at +9714 3867728 or mail: info@groupisd.com or visit www.groupisd.com