Last year, Molson Coors, the esteemed purveyor of watered-down frat-party beer, ran a jarring ‘experiment.’ In a discreet building in downtown Los Angeles, 18 subjects were instructed to watch a strange video featuring a synth-laden soundtrack and natural imagery interspersed with glimpses of Coors Light cans. The participants were then asked to drift off to sleep while listening to an 8-hour soundtrack featuring audio from the video.

Coors’ stated goal was science-fiction worthy: The company wanted to “shape and compel [the]subconscious” into dreaming about beer. Shockingly, it seemed to work. Around 30% of the participants reported that Coors products made an appearance in their dreams.

The average person is exposed to up to 10k ads per day.

They’re peppered along roadway billboards and bus stops. They’re squeezed into podcasts, newspaper folds, and mailboxes. They pop up by the dozen on websites, and plague social media feeds like some kind of fungal disease.

Ads have infiltrated every facet of our lives. And now, researchers say our last remaining respite — the dreamscape — is under siege. The Hustle spoke to half a dozen leading sleep scientists and researchers to better understand advertisers’ efforts to infiltrate our dreams.

The manipulation of dreams

Humans have long attempted to orchestrate their dream content. As far back as 1350 BCE, Ancient Egyptians would draw on their hands prior to nodding off, in a bid to summon nocturnal wisdom from deities. Over the centuries, cultures enlisted a plethora of similar techniques, from fasting to consuming spicy foods.

Today, dreams — and sleep, for that matter — are still a largely unexplored and mysterious terrain. But Robert Stickgold, a professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School who has studied dreams for decades, says that in the last 20 years, brain activity technologies have enabled us to gain a better understanding of dreams.

“All night long, your brain is reprocessing memories from the previous day, connecting them with other memories, sifting through the residue to decide which ones to keep, and stabilizing them.”

“Our dreams,” he says, “are literally creating who we are.”

Now, here’s where things get a bit Inception-worthy.

Academic work has suggested that external stimuli like smells, lights, and sounds can be enlisted to alter the content of our dreams. In a 2000 study, for instance, Stickgold and his Harvard colleagues had subjects play 7 hours of Tetris over 3 days, and found that 60% reported dreaming about the game. In subsequent work, he found that even people with amnesia who had no recollection of playing Tetris had the dreams.

Researchers broadly call this practice “Targeted Dream Incubation” (TDI), and in simplified terms it typically works like so:

- An association is formed during waking — say a pairing of sounds and visuals, or scents.

- When someone is drifting off into hypnagogia (the state between wakefulness and sleep), and the sound or scent is introduced, it triggering related dreams.

Adam Haar, a Ph.D. student at MIT, recently worked with a team to develop a wearable device that mechanizes this process. The sensor-equipped glove detects when someone has drifted off into a hypnagogic state, then repeatedly plays a prerecorded audio cue — usually a single word. In one experiment, participants who were prompted with the word “tree” reported dreaming about trees 67% of the time.

Haar says dream intervention has a variety of potentially positive applications. It could be used to:

- Alleviate psychiatric conditions like depression and PTSD

- Augment our creativity

- Help us learn

- Combat addiction

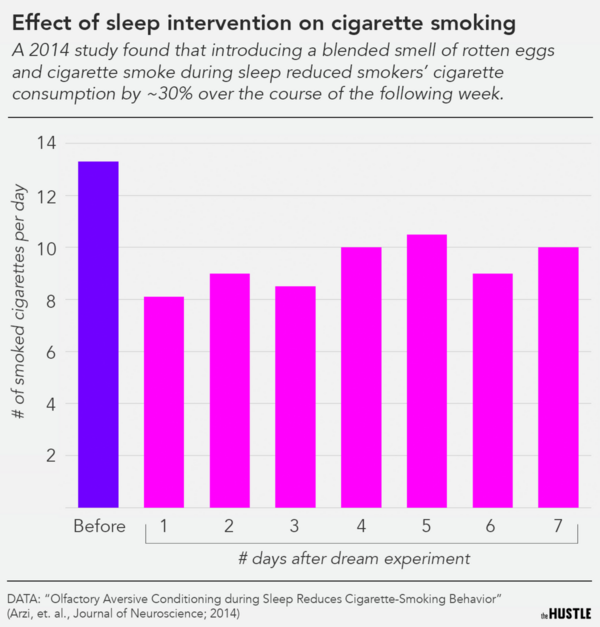

There is some evidence to back this up. A 2014 study found that introducing a blended smell of rotten eggs and cigarette smoke during sleep reduced smokers’ cigarette consumption by ~30% over the course of the following week.

But lately, something has been plaguing Haar. “On one hand, dream manipulation is gaining acceptance and has all these great applications,” he said in a recent interview. “And on the other hand, it’s, ‘Oh shit, the advertisers are coming.’”

The best case, adds Haar, is that dream intervention will deepen people’s relationship with their dreams. The worst case is that it will cheapen it. “I think it’s going to be a bit of a battle,” he says. “And I think that battle has already started.”

Nefarious actors

In early 2021, Bobbi Gould, a Los Angeles-based travel writer, says she came across a vague ad on Craigslist from a “big brand looking for willing sleepers.” She’d always been interested in dreams, and the gig paid $1k. So she and her boyfriend decided to sign up.

A few days later, she says she found herself in an old warehouse with 17 other people, hooked up to an EEG machine, surrounded by Molson Coors marketers. Gould was told to watch the Coors video — complete with hypnotic waterfalls, lush green landscapes, and flashes of Coors products — then doze off to an audio recording of sounds from the video. Over the next 8 hours, she had a variety of “weird Coors dreams.”

“I had one where I was on a pogo stick jumping around with Coors products,” she tells The Hustle. “In another one, I was on a plane dropping Coors cans on people and they were cheering for me.” At the end of the ordeal Gould was roped into a focus group to discuss the experience. “We all felt like lab rats,” she says. “They were trying to implant Coors into our brains. It just didn’t really sit right.”

Coors isn’t the only big brand looking into dreams as potential ad space:

- Microsoft has explored ways to make pro gamers dream of their favorite Xbox video games.

- Sony’s PlayStation has advertised a new game on the premise that it induces dreams about Tetris.

- Burger King rolled out a Halloween-themed burger in 2018 that it claimed was “clinically proven” to induce nightmares.

- Several large airlines have reached out to Haar for help with commercially driven dream-incubation projects.

Marketers have quietly been studying the viability of using dreams to alter our purchasing behaviors. And in a recent survey run by The American Marketing Association-New York, 77% of marketers said they had plans to use technology to influence dreams within the next 3 years.

Sleep researchers don’t want to wait for that to happen. Last summer, Stickgold, Haar, and nearly 40 other scientists signed an open letter warning that, without action, dreams could soon become “a playground for corporate advertisers.”

What might that nightmare look like? Stickgold says that advertisers could, in theory, use smart speakers — 126m of which are now installed in US homes — to market products to us in our sleep.

Many say that the technology to do this is nearly there. Google’s Nest Hub, for instance, can measure your breathing during sleep and detect your coughs and snores. “When you’re awake, you have a whole collection of filters and mechanisms to evaluate information and filter out ads,” says Stickgold. “Your sleeping brain can’t do that. It assumes that whatever is activated during sleep is being activated internally, not by outside forces.”

Kathleen Esfahany,anundergraduate researcher who works with Haar at MIT, fears that “addictions and other problems that exist in the real world could just be worsened” by advertisers.

More nefariously, this could be done without us even realizing it. Sara Mednick, a sleep researcher and professor of cognitive science at UC Irvine who co-signed the letter, is particularly concerned about the privacy implications of dream ad incubation. “Our dreams are our last sacred space,” she says. “We’re super vulnerable during our sleep and we may not even know we’re being exposed to these techniques.”

Deirdre Barrett, a Harvard professor and renowned dream expert whom Coors consulted with for its video, sympathizes with the fears raised by her colleagues but feels that some of the fears are overblown.

“My read of the scientific literature is that there is scant evidence to suggest that sleep- or dream-related advertisements would be nearly as effective as ones presented to a wide-awake consumer,” she says. Tore Nielsen, the director of the Dream and Nightmare Lab at the Université de Montréal, shares this opinion.

“I don’t think it is very realistic at all for advertisers to manipulate our dream content — especially not against someone’s will,” he says. “New tech is showing some signs of progress, but we are nowhere near having a ‘problem’ with ‘unconscious mind control,’ in my opinion.”

Ad experts have also pointed out that tracking viewability metrics — a key component of any successful ad campaign — would be virtually impossible in the dreamscape.

“You can’t track whether someone clicked on a dream ad or signed up for a dream email service,” writes tech journalist Shoshana Wodinsky, “or even if they actually comprehended what the hell they were looking at in the first place.” And even if the dystopian future of dream ads does come to fruition, critics say current regulations already shield consumers from manipulation.

Section 5 of the Federal Trade Commission Act prohibits“unfair or deceptive acts or practices” in commerce, including advertising that a reasonable consumer wouldn’t recognize to be an ad. Barrett thinks that language is broad enough to cover emerging “markets” like dreams.

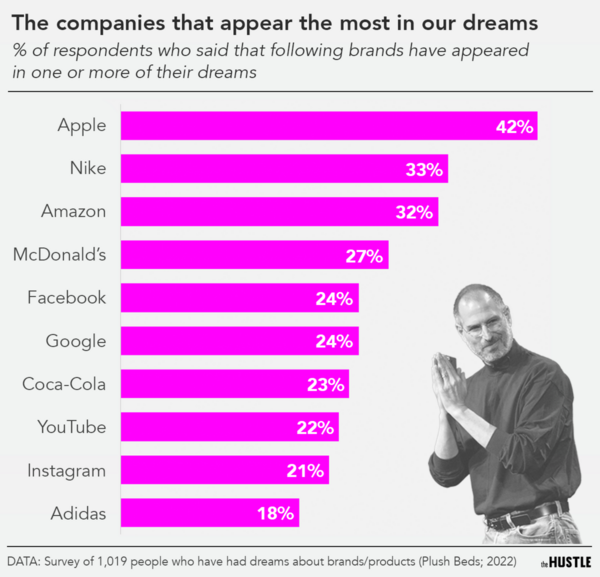

Regardless, advertisers seem to be doing just fine without directly intruding on our dreams. A recent survey by a luxury mattress company found that 7 in 10 people have had a dream about a brand as a result of interacting with regular ads, or using a product in daily life. And more than half of them said those dreams made them want to interact with those brands even more. If you’re worried about a potential ad dystopia, take a look around. We’re already living in one.

—

This article first appeared in www.thehustle.co

Seeking to build and grow your brand using the force of consumer insight, strategic foresight, creative disruption and technology prowess? Talk to us at +971 50 6254340 or engage@groupisd.com or visit www.groupisd.com/story