A social movement is not a corporation. Do the same branding rules apply?

Black Lives Matter is one of the most widespread social justice movements of this decade—and it has galvanized its followers with a powerful visual identity and branding.

Yet, since Black Lives Matter is a movement and not a brand, there’s no obvious way to control how its symbols are used, or by whom. The Black Lives Matter logo and hashtag have been appropriated by outside interests, ranging from corporations to ideologically opposed protest groups like All Lives Matter and Blue Lives Matter. Even other factions within the broader Black Lives Matter movement that share the founding organization’s core philosophy may use its graphics and language, even if their missions run contrary.

Alicia Garza—a cofounder of the Black Lives Matter organization and cocreator of the hashtag with Patrisse Cullors and Opal Tometi—has been grappling with these problems, along with the role of branding in her mission and the broader social justice movement around race in America.

“What’s rattling around in my head is that I think it’s an open question for our movement,” Garza says of branding at activist organizations. “Because we’re not building businesses who depend on brands for recognition so they can make money, I think a lot of [organizers]don’t pay attention to the salience of what it means to have a symbol people can recognize you by, and maybe some of us misunderstand [branding].”

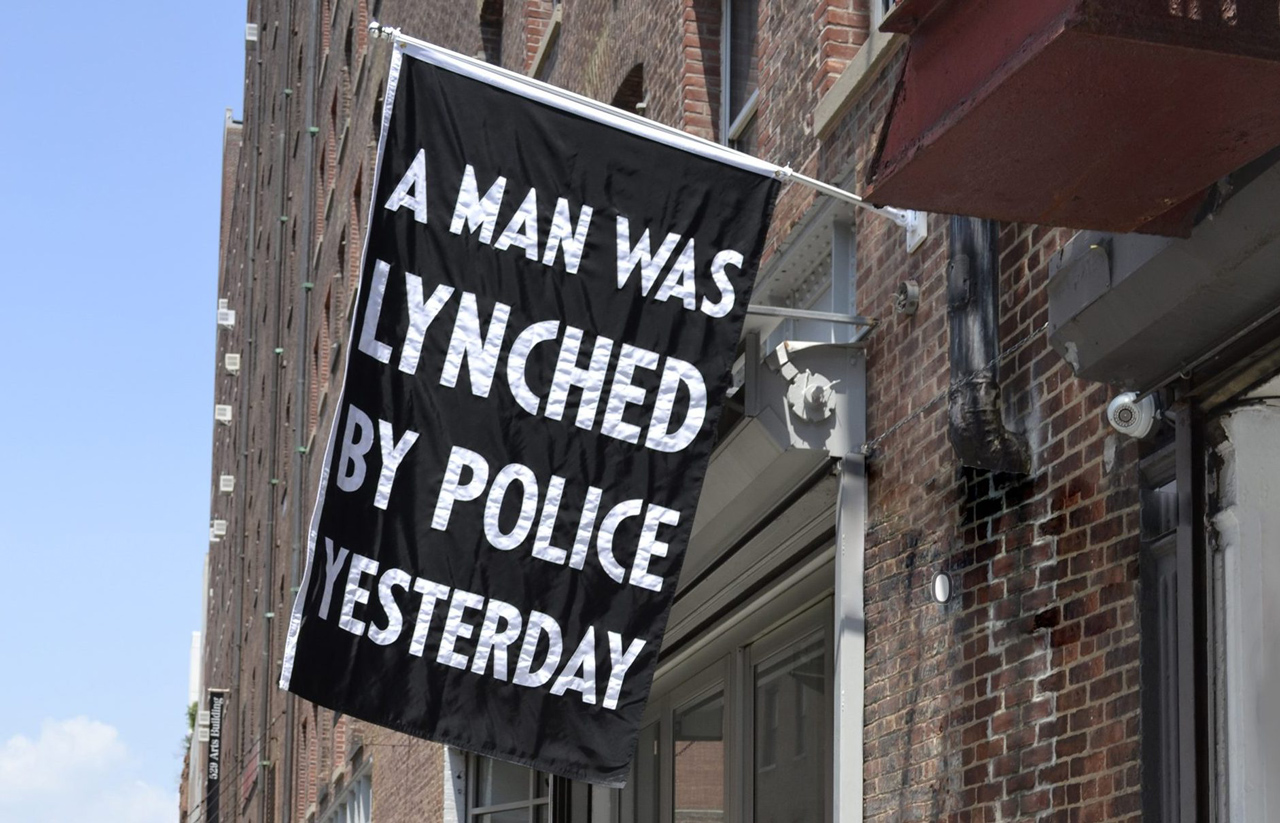

Dread Scott/Jack Shainman Gallery via PBS/News Hour

DESIGN THAT FUELED A MOVEMENT

Visual emblems are the fuel of social justice movements. In the 1960s, the Berkeley Political Poster Workshop’s silk-screen signs spread the antiwar movement. In the ’70s, artist and AIGA medalist Emory Douglas used graphic design to mobilize activists around the Black Panthers. This spring, the artistDread Scott revived an NAACP banner from the ’20s as a symbol for the Black Lives Matter movement.

This is a long way of saying that a picture is worth 1,000 words. Garza and her collaborators have understood the importance of branding from the beginning, when they sought out designers who could give their nascent movement a visual voice.

Black Lives Matter originated in 2013 when a jury acquitted George Zimmerman of manslaughter after he shot and killed Trayvon Martin, an unarmed black teenager. Garza, an activist, wrote a Facebook post about the verdict with the phrase “Black people. I love you. I love us. Our lives matter.” Cullors riffed on the message to create the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter, and a slogan was born.

The creators of the nascent movement enlisted the Design Action Collective, an employee-owned Oakland-based creative studio that typically works with progressive nonprofits and social change organizations, to create its logo. At the time, the logo was simply for its Tumblr page.

While “branding” is typically more of a business strategy than a tool for grassroots activism, establishing a visual identity was crucial for Black Lives Matter. “In terms of social movements, I don’t think that we think about things like branding or image identification, but we look for recognizable symbols that tell us a few things,” Garza says. “One [reason]is that it tells us that it’s legitimate—this is something coming from somebody I trust. Two, I think what’s important about this kind of design is that a lot of our work is not just marching and protesting. It’s about different ways we’re able to seep into the public consciousness so that our ideas become common sense as opposed to outlying ideas.”

Like many of Design Action Collective’sclients—which include a local chapter of the ACLU, the Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation (GLAAD), and Greenpeace—they had no time and a limited budget, so “we were winging it based on what we knew about social movements and the organization,” says Josh Warren-White, a self-taught graphic designer who joined the studio by way of AK Press, a Berkeley publisher of radical social publications.

With a three-day turnaround time, Design Action Collective created a simple wordmark using the font Anton—which is similar to Impact but available for free online—rendered as all-caps black letters on a yellow background. “It’s bold, strong, militant, and carries strength and tone,” Warren-White says. “Being easily replicable was the main goal since we know within movements people don’t have budgets to do professional printers—they’re hand painting logos, and the level of skill to replicate a logo by hand varies. We wanted to make something that people could pick up and use in myriad ways.” Indeed, JPEGs of the logo are easy to find online.

The lesser-used half of the Black Lives Matter logo is an illustration of a man in a hoodie holding a dandelion with its seeds blowing in the wind—a metaphor for seeding a movement. A group of protestors with their fists in the air marches behind him. Yet, since Black Lives Matter was born through a very potent slogan and hashtag, it makes sense that a wordmark, not a symbol, was the logo that ultimately took hold. “Having something that was a lot simpler—just a wordmark—ended up being just as powerful and a better shorthand than a complex illustration,” Warren-White says.

APPROPRIATION BY CORPORATIONS—AND OPPONENTS

Since 2013, “Black Lives Matter” has eclipsed the organization that coined the phrase and hashtag. It’s more than a slogan or an entity: It’s a full-blown social movement.

“I don’t know if we imagined that it was going to blow up as much as it did,” Garza says. “When Black Lives Matter became a network of chapters that are organizing on the ground across the country, it became a slogan and a demand that was picked up by protesters in Ferguson and Baltimore. It was an incredible honor in some ways, and at the same time it reminds us how much bigger than us this is and why it cannot be proprietary in the way a corporation like Nike would have it.”

But with its success has come growing pains, as the conversation about race and police brutality evolves and reflects even more voices. Black Lives Matter, the organization and network, has had to issue lengthy clarifications responding to common misconceptions about its mission.

“Some level of ‘brand appropriation’ for a social movement is a good thing to have,” Warren-White says. “You want people to identify with it, to make it their own, and to use it. Those are good issues. With Black Lives Matter, it’s complicated because it’s a logo created for the Black Lives Matter network, but it helped to ‘cohere’ a broader movement.”

Corporate co-opting of the slogan is one problematic aspect of the brand’s success. Mazda has its “Driving Matters” campaign and Verizon has“Connections that Matter,” for example. “It starts to create some fatigue with people and it starts to take the salience out of the message that’s intended,” Garza says.

Yet to Garza, challenging mainstream appropriation by commercial entities is only part of the problem. What concerns her is when the branding is used by people whose practices or beliefs run counter to the organization.

In some cases, groups who have appropriated the Black Lives Matter branding have even posed safety risks for people within the organization, where activists and organizers have received threats, along with visits from law enforcement and the FBI. Last year, protesters in Minneapolis holding black-and-yellow “Black Lives Matter” signs were heard chanting, “Pigs in a blanket. Fry ’em like bacon.”

“That gets captured on video and then it goes viral so then people start this narrative of ‘Black Lives Matter wants to kill cops,'” Garza says. “That’s nothing we’ve ever said or advocated for anywhere. But yet, the simple act of somebody holding a banner with our recognizable elements have really attached that narrative to our organization and our work. We spend a lot of time—too much time, in my opinion—really trying to counter this narrative that isn’t ours because somebody irresponsibly used a piece of our design to further their own political goals.”

Then there is the emergence of the hashtags #AllLivesMatter and #BlueLivesMatter, which borrow the exact syntax of Black Lives Matter and, in the process, reduce its impact.

“When people use All Lives Matter or Blue Lives Matter, it shows that they are willfully ignoring conditions that impact black people in a negative way,” Garza says. “In many ways, it shows the ways in which the lives of police officers are valued more than black lives, and it highlights the ways in which we fail to hold police accountable when they act outside of the law at the same time that they are supposed to be upholding the law. If people can say ‘All Lives Matter’ while stepping over people living on the streets, they’re being hypocrites. So in both cases, both aberrations are ways to distract us from what’s really happening in our communities and, more importantly, distract us from what’s necessary to fix it.”

HOW DO YOU CONTROL A BRAND WITH NO OWNER?

While companies like Louis Vuitton and Gucci often do sue over the misuse of their trademarked logos and slogans, it’s not quite the same with the use of a social movement’s logo. Businesses create brands for commerce, whereas social movements create them for the people.

“In corporate branding, there’s more control over how the brands are used—within social, there’s little control. It takes on a more organic quality,” Warren-White says. “It’s really important in creating that visual cohesion that a movement can have because it helps people see themselves within it and say, ‘This is bigger than me.’ For corporations, that’s what their brand would end up doing, too.”

Though Garza doesn’t want to legal action to “use a broken system to hold people accountable” for affronts to the brand and what it stands for, if more severe cases arise, that might be the last resort. “For Black Lives Matter, we see accessible, sharable design that is accountable to the communities that are impacted [by injustice]as a core component of movements,” Garza says. “It’s a piece that’s often ignored, which is why we get driven crazy by people who use it in a way that’s incompatible. Because it really prohibits the people who need it from having access to it in the way that they should.”

So far, no lawyers have been involved. Instead, when Garza sees the network’s logo deployed inappropriately, she and her team try to get in contact with the person who’s behind it and ask them to stop. Or they rely on their robust social following to find “creative ways” to keep misuse in check.

She recently saw a Facebook page circulate a sharable logo even though they weren’t affiliated with the organization. “With the sharable graphic [situation], there were lots of people who responded and said, ‘I had no idea [this wasn’t official], I thought this was y’all. Should we call Facebook? Should we report the page? Should we do a write-in campaign?’ People had commented so much on this person’s fake page that they were blocked from the site. That’s an example of how committed our internet community is and how the internet community mobilizes itself to be able to do what a lawyer would do. A lawyer says, ‘You’re going to face legal or financial sanctions.’ In this case, people are really able to leverage social sanctions, which, in the social media space, does mean something to people.”

“When we created Black Lives Matter, we wanted it to be a tool and a resource for organizers, for black people who were advocating and fighting for justice, and we wanted it to be as successful as possible for that group of people,” Garza says. “But I think that what we’ve found over time is we had to take more steps to really engage in a level of protection around the integrity of this, which means legal steps. So unfortunate, but true.”

Despite these growing pains, Black Lives Matter has succeeded in raising awareness about the racial injustices that have been happening for decades in America, and has become a rallying cry of protestors, activists, and people who believe in fixing the country’s broken perceptions of race—whether or not they’re “officially” affiliated with the network.

“Maybe the theme of this conversation is it’s a blessing and a curse,” Garza says. “In general, more people are using it appropriately than are using it inappropriately. That’s the blessing and that’s exactly what we wanted when we designed this. We wanted it to be accessible to people who were interested in helping to move the same vision that we’re trying to move.”

While Garza and her organization may have their ideal of what the brand stands for, the future as a whole remains uncertain. A recent New York Timesstory tracked the hashtag’s use and found that public perception of its positive or negative connotations vacillate. “As designers, we create the logos,” Warren-White says. “But it’s the social movements that create the brand.”

[All Images (unless otherwise noted): via Black Lives Matter]

This article first appeared in www.fastcodesign.com