In January 2021, five craftswomen from Mozambique and three designers from The Netherlands came together in Linga Linga–a tiny peninsula in Mozambique–for a three-week design residency. It resulted in two prototypes: a lampshade that lights up in the dark, and a small handbag that charges a phone.

The workshop was a collaboration between several studios from Mozambique and The Netherlands, including Pauline van Dongen, a Dutch fashion designer who specializes in smart textiles and clothing. Van Dongen believes in a future where everything is solar-powered, so she’s planning the world’s first Solar Biennale later this year. And her timing couldn’t be better.

Solar power is booming. In the last decade alone, in the U.S, the number of solar panels installed has gone up by 40%, while the cost to install them has dropped by more than 70%. Now, the Biden administration wants the country to generate almost half of its own electricity from the sun by 2050 (compared to only 4% in 2020). The infrastructure bill that passed in November includes billions of dollars for clean energy projects, building momentum for more innovation in the industry.

Already, an increasing number of designers and startups across the globe are leading what Van Dongen calls the “solar movement.”As a result, solar applications are growing more and more diverse: a company in the U.S. has developed solar cells that can be integrated into windows. Another has transformed dreary solar panels into patterned masterpieces by redesigning how the silver lines look on the panels. Elsewhere, designers are creating colored glass tables that can absorb energy from daylight and charge your devices, clothes that can charge your phones, and textile roofs that can stretch over buildings while harnessing energy from the sun. As solar energy becomes more affordable, the options are increasing, and 2022 may well become a banner year for solar energy.

The Solar Biennale will be hosted in Rotterdam, bringing together frontrunners in solar energy including designers, researchers, and philosophers. It was conceived by Van Dongen and another powerhouse in the solar-design industry, Dutch designer Marjan van Aubel. For them, the prevailing narrative around solar so far has been technocratic, focusing on paybacks and efficiency. “That makes it hard for people to relate and connect with solar energy on a more cultural level,” says Van Dongen.

This is where design comes in. Designers have the ability to take a piece of technology and help people understand it and engage with it. Unlike other sources of renewable energy, solar energy comes in many forms: you can’t put a wind turbine in your backyard (although an ingenious new wall may change that), but you can wear a solar-powered jacket, retrofit your house with solar windows, or find ways to integrate solar into your everyday life.

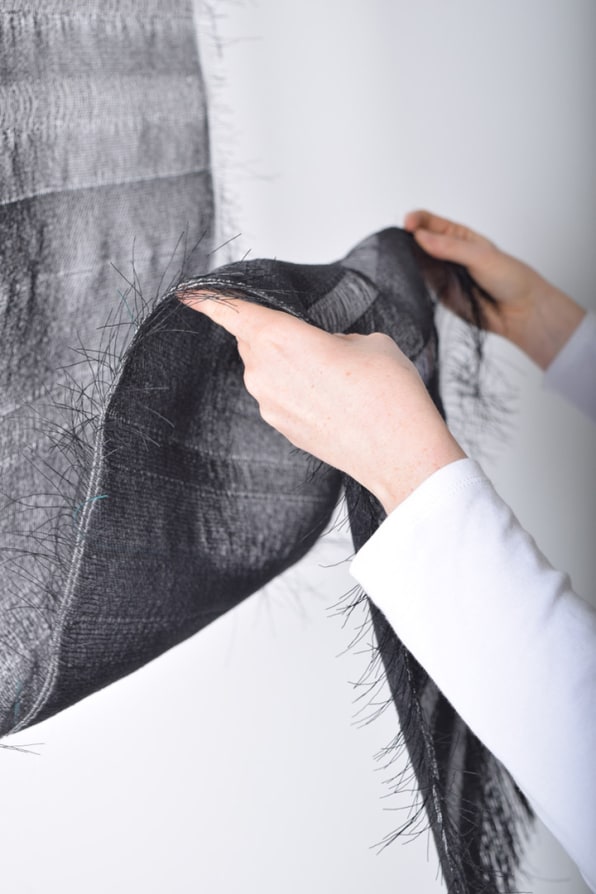

Van Dongen is currently working with a Dutch textile architecture company called Tentech to develop a structural woven fabric with thin-film solar panels woven in. The aim is to develop a textile that can be used as a building material, so it has to be fire retardant and durable, too. “This opens up new applications for solar technology to be integrated in large tents and textile facades,” she says. It would also help a solar-powered building look good.

For now, most commercial solar panels are designed to be attached to a rack that is secured to the ground or screwed directly into the roof. But an entirely new movement is emerging, where our buildings themselves become the panels. This is called Building Integrated Photovoltaics. The most famous example is Tesla’s solar shingles, but more and more examples are cropping up.

This year’s Netherlands pavilion at Dubai’s Expo was powered by translucent solar cells integrated into a colored glass roof, courtesy of designer Marjan van Aubel. And in Paris, a soon-to-be-completed duo of towers (by French starchitect Jean Nouvel) will feature an entire facade made of 825 gold-hued panels. These were designed by Solar Visuals, a Dutch company that develops building facade modules that can take on any shape, and any patterns imaginable.

At the end of the day, the more options individuals and businesses have to make the switch to solar, the more likely they are to adopt it. Garrett Nilsen is the acting director of the Department of Energy’s Solar Energy Technologies Office, which supports funding in photovoltaics and other solar technologies. Nilsen says that the steady decline in cost has been driving solar adoption, but much of our experience so far has been filled with “transactional friction” like securing permits and figuring out how much you’ll save on bills in the long run. “Now that we’re at a lower cost level, maybe the friction comes from elsewhere, such as how does something look?” he says.

Each year, the Solar Energy Technologies Office receives $280 million from Congress that it uses to fund a wide array of solar energy research and development efforts through training programs and competitions like its much-coveted American-Made Solar Prize. (Now in its fifth year, the latter grants a $3 million prize to accelerate solar innovation.)

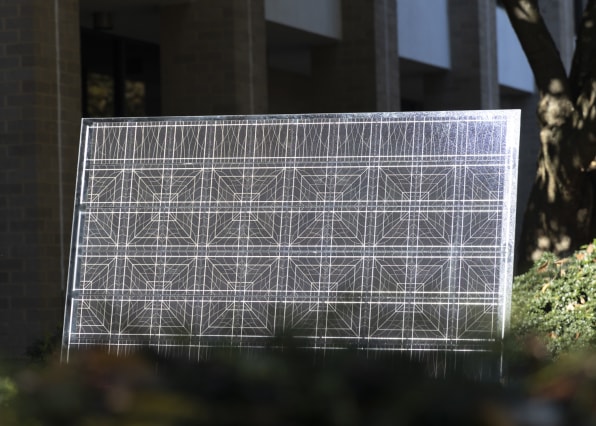

Over the past few years, SETO has been focusing on a number of areas, including integrated architectural solar solutions that could help make solar appealing to more people. In 2016, SETO awarded $1 million to a startup called Sistine Solar. Based in Sommerville, Mass., the company developed a set of graphic overlays that can match any roof esthetic, from terra cotta to a fully customizable look with a corporate logo on the roof. Since then, the company’s panels have been rolled out in nine states around the country. And just this year, SETO granted $405,000 to a new startup called Asoleyo, which creates “proudly solar” panels with intricate patterns. “There is absolutely room for real creativity in terms of what the future of solar can look like,” says Nilsen.

In the end, the adoption of solar energy could work like a ripple effect. More government grants lead to more innovation, which leads to more private investments. In 2020, venture capital investment in climate tech reached a record high of $16.4 billion. For now, Biden’s Build Back Better plan, which proposed $1.75 trillion in social and climate spending, is dead. But the solar outlook is promising even without it. “We’re going to have a huge 2022 for solar, regardless of the big bills bouncing around,” says Bill Nussey, the founder of the Freeing Energy Project, whose mission is to accelerate the shift to cleaner, cheaper energy.

Nussey has spent the past three years interviewing more than 300 solar experts and innovators for his latest book, Freeing Energy. For him, everything lies in smaller-scale projects, like a single school installing solar panels on its roof, or even a small neighborhood opting into community solar. “If you want to work on climate change, you need to make beautiful products and you need to let communities take charge,” he says.

Back in Mozambique, the collaboration between the solar designers and the local craftswomen culminated in a new material called “solar palha,” which translates to “solar palm tree” and was used to create the lampshades and handbags that are sold on local markets and provide income for the craftswomen. The material was born in the span of just a few weeks, but it has made solar energy tangible in ways that large-scale solar farms haven’t. “For the women [in Mozambique], solar energy has become more accessible and understandable, ultimately empowering them to strengthen their position within the community,” says Van Dongen.

…

This article first appeared in www.fastcompany.com

Seeking to build and grow your brand using the force of consumer insight, strategic foresight, creative disruption and technology prowess? Talk to us at +971 50 6254340 or mail: engage@groupisd.com or visit www.groupisd.com/story