In the eight months since I wrote Cars and the Future, there has been an explosion in news about the future of transportation, much of it in the last few weeks:

- Ford announced plans for its own car-sharing service built around self-driving Fords

- Elon Musk penned a second master plan envisioning a future car-sharing service built around self-driving Teslas

- Nutonomy launched a trial in Singapore of its own ride-sharing service built around Renault and Mitsubishi vehicles modified to be self-driving

- Uber announced its own self-driving trial in Pittsburgh in partnership with Volvo. Uber alsoacquired self-driving startup Otto, founded by former members of Google’s self-driving team

- And, speaking of Google, Alphabet executive David Drummond stepped down from Uber’s board a day before the company announced an expansion of its Waze-based ride-sharing service from Israel to Uber’s home city of San Francisco

These five bits of news are presented in roughly the order they matter; Uber and Google matter most of all.

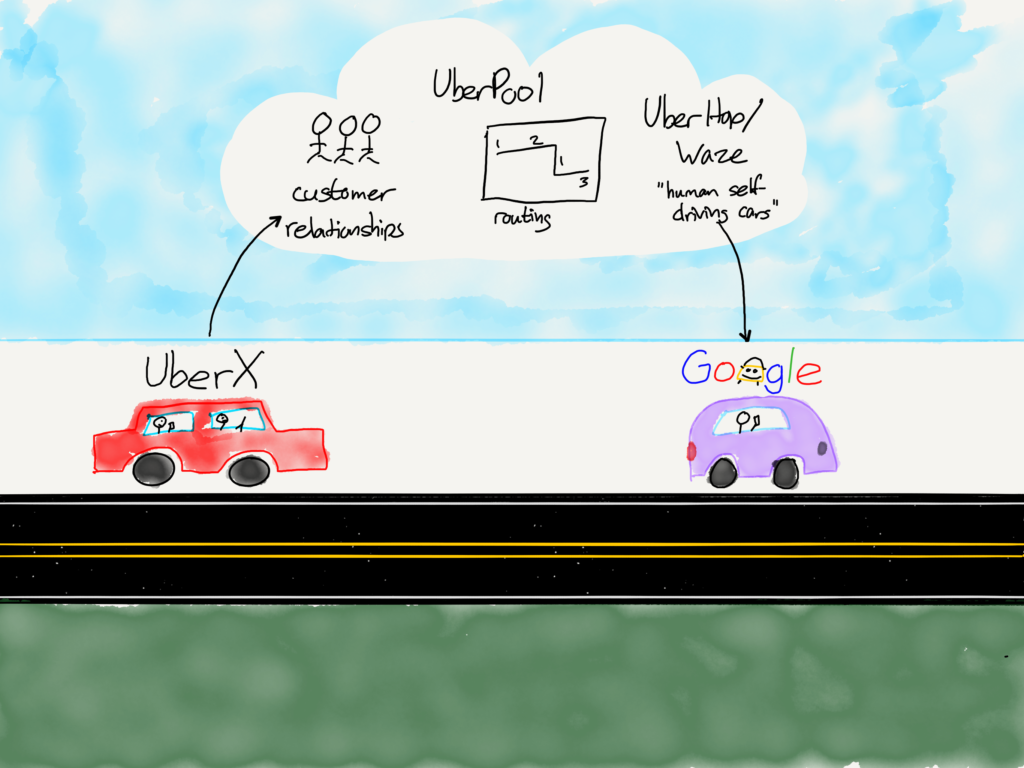

FROM UBERX TO GOOGLE’S SELF-DRIVING CARS

When thinking about the future of transportation-as-a-service, it’s tempting to draw a straight line from UberX to Google self-driving cars:

Uber CEO Travis Kalanick can certainly see the connection; he told Bloomberg earlier this month:

“The minute it was clear to us that our friends in Mountain View were going to be getting in the ride-sharing space, we needed to make sure there is an alternative [self-driving car],” says Kalanick. “Because if there is not, we’re not going to have any business.” Developing an autonomous vehicle, he adds, “is basically existential for us.”

The problem for Uber is that their dominant position in the ride-sharing market is predicated on the two-sided market of riders and drivers, which I explained two years ago in Why Uber Fights:

Driver and rider markets do interact, and it’s that interaction that creates a winner-take-all dynamic…In the case of Uber and Lyft, ride-sharing is (theoretically) habitual, both companies will ensure the prices are similar, and the primary means of differentiation is car liquidity, which works in the favor of the larger service. Over time it is reasonable to assume that the majority player will become dominant.

That is indeed how the ride-sharing market has played out: as of earlier this year Uber provided over 80% of rides in the United States (the only market Lyft competes in), despite Lyft’s determination to spend hundreds of millions in subsidies and free rides. And, on the flipside, Uberleft China earlier this month, tired of spending their own billions in a futile attempt to displace the dominant Didi.

Self-driving cars change these market dynamics in two important ways: first, drivers are no longer a scarce resource, which means there are no longer two-sided market forces at play. Second, the single best way to change consumer habits and preferences is through lower prices, and eliminating drivers is the most obvious way to do just that.

Small wonder then that Uber is investing so heavily in self-driving cars, including hiring a huge number of Carnegie Mellon researchers (thus the Pittsburgh location of the self-driving trial), as well as paying ~$680 million for Otto.

Kalanick told Business Insider that Uber is still behind:

I think we’re catching up. Look at some of the folks and how long they’ve been working on it. Lots of respect for an area that they’ve pioneered, and we’ve got to do some catch-up. And that’s OK, but it means we gotta wake up early and we’re going to bed late.

I’ll take Kalanick at his word; Uber, though, still has some very important advantages that make this race a bit more complicated than it seems, and the journey I depicted above a lot less linear than it may appear.

THE FIVE COMPONENTS OF TRANSPORTATION-AS-A-SERVICE

Drivers and riders are important to understanding the future of transportation-as-a-service (TaaS), but they are not the only pieces that matter — and not the only areas where Uber still has an advantage. I see five components that really matter:

- Drivers

- Cars

- Mapping

- Routing

- Riders

The shift from an UberX model to self-driving cars will require changes in every component.

TaaS 1.0: UberX

It’s clear why drivers and riders are the most important pieces here: drivers bring their own cars, existing mapping solutions are good enough, and routing is relatively simple. To be sure, thatrelatively modifier is important: managing millions of matches a day between drivers and riders is a hugely complicated undertaking, and the fact that Uber has been working on the underlying algorithms for years is a big advantage. It’s also an advantage that will become ever more critical.

TaaS 1.5: UberPool

UberPool is arguably the most important service Uber has launched to date, and looking at the pieces that go into it explain why:

- Drivers: the same as UberX

- Cars: the same as UberX

- Mapping: the same as UberX

- Routing: massive increase in complexity over UberX

- Riders: change in expectations (and behavior with regard to pick-up and drop-off points) relative to UberX

It’s the routing piece that is the most important; Uber investor Bill Gurley has called the development of the necessary algorithms to make UberPool a success a BHAG: Big Hairy Audacious Goal, and it’s an investment that will be critical for Uber going forward.

First, as Gurley’s title suggests, getting the algorithms behind UberPool right is an incredibly complex problem. It’s basically the traveling salesman problem on steroids, and the only real way to solve it is to slowly but surely work out heuristics that work in real world situations. Combine that reality with the fact that Uber has a dominant share of drivers and riders, giving the company sufficient liquidity to offer UberPool in multiple markets, and the result is that Uber is undoubtedly far ahead of competitors — present and potential — in solving these problems.

The reason this matters is that building a self-driving car is like building a smartphone: it’s a hard problem, to be sure, but it’s only half of the equation when it comes to transportation-as-a-service. After all, just how useful would an iPhone or Android device be without the cloud? Similarly, a transportation-as-a-service company built around self-driving cars not only needs cars that can drive themselves, but an entire infrastructure on the back-end that tells those cars exactly where to go in a way that maximizes what will undoubtedly be a massive capital investment in the cars themselves.

This is likely the motivation behind Google’s Waze-based ride-sharing service. Kalanick may be right that Google is ahead when it comes to self-driving cars, but they have a lot of catching up to do when it comes to telling those cars where to go.

TaaS 2.0: Human Self-Driving Cars

One of the more interesting facts about the new Waze service is that it is true ride-sharing: Google is capping the price at 54 cents a mile, which means it’s impossible to make money by simply driving-for-hire. More prosaically, that happens to be the IRS standard mileage rate, which means Google can plausibly claim their service is facilitating, well, ride-sharing and the sharing of gas money without all of the complications of hiring contractors.

Still, true ride-sharing is itself an important transportation-as-a-service evolution that I wrote about last year. In the short to medium-term, catching a ride with someone already headed in your direction actually has even better economics than self-driving cars, given that the car is a sunk cost and the driver is going that way anyways. In that article I called this sort of car-pooling service “human-powered self-driving cars.”

Note that this again marks an important shift in the components in transportation-as-a-service:

- Drivers: because they are already headed in that direction, they are effectively free

- Cars: because they have already been bought for the purpose of transporting the driver, they are effectively free

- Mapping: the same as UberX

- Routing: slightly more complex than UberPool

- Riders: similar experience to UberPool

Uber launched UberCommute just a few weeks after that article; given that the economics of UberCommute are approaching those of self-driving cars, that means the company is ahead when it comes to figuring out the business model as well.

TaaS 3.0: Self-Driving Cars

Whenever self-driving cars do arrive, nearly every piece in the transportation-as-a-service puzzle will be different from today’s UberX:

- Drivers: non-existent!

- Cars: self-driving, which means they will likely be very expensive at least at the beginning, requiring significant capital costs

- Mapping: massively more detailed

- Routing: similar complexity to UberPool

- Riders: similar economics to UberCommute/Waze

Note that there are two critical leaps that need to be made: cars and maps. Google is clearly well ahead in maps, but Uber is investing $500 million to catch up, even as it does the same for self-driving technology.

The point of this analysis, though, is to highlight that for all the work Uber has to do, they are by no means doomed because of Google’s entry, because there isn’t a straight line from UberX to Google’s self-driving cars:

Indeed, Uber has their own advantages in routing, business model, and customer attachment, and those are just as formidable and potentially more defensible than Google’s tech leadership.

HANDICAPPING THE FUTURE

With this framework in mind it’s easier to understand why I ranked those five pieces of news the way I did:

- Ford certainly knows how to build cars, but self-driving technology is a software problem; there is no evidence to suggest that Ford has the capability to leap ahead of Google or Uber. Moreover, while Ford’s relatively slim margins may make a ride-sharing service attractive, nearly every aspect of the company would need to transform itself from a product model to a service model, and that is even less likely than the company leading the way in self-driving technology. I think it is much more likely Ford will eventually partner with Google or Uber as an OEM.

- Tesla is a much more technologically advanced company than Ford and is already in the mindset of building computers on wheels. Moreover, it has thousands of cars on the road today both capturing data and beta-testing self-driving technology (for better or worse). However, Tesla faces several significant obstacles in building a service business: it has no routing capability; it sells its cars as products, not as a service; and, frankly, it has its hands full building the Model 3 before its negative cash flow catches up to it.

- Nutonomy is very interesting, not only because of their technology, but also because of the smart way they are dealing with perhaps the most important piece of transportation-as-a-service: the government. I have argued for years that Singapore was likely to be the first place where self-driving cars take off: the technology already works as long as you get rid of those pesky human drivers, while Singapore has placed strict limits on automobiles for years, and, to put it delicately, Singapore has the government structure to get rid of non-self-driving cars completely. By starting there Nutonomy has a big advantage when it comes to real-world experience and iteration, and could springboard from Singapore to other urban areas.

That leaves Google and Uber, and, despite yesterday’s news, I still like Uber’s chances.

First, it matters that the development of self-driving cars is, in Kalanick’s words, “existential” for the company. Never underestimate the motivating power of simple survival, and, on the flipside, keep in mind how poorly Google has done in any business that is not advertising-based.

Second, I suspect Uber’s routing advantage (as infuriating as it may be when you are matched with a driver who is going the wrong way) is a real one: telling cars where to go at scale is an incredibly difficult problem and Uber has a multi-year head start.

Third, any discussion of the threat self-driving cars poses to Uber tends to imagine a world where there are magically tens of thousands if not millions of self-driving cars everywhere immediately. That simply isn’t practical from a pure logistics standpoint; the time it will take to build all of those cars — and, crucially, get government approval — is time Uber has to catch up.

Moreover, it’s not at all clear that Google will be willing to make the sort of investment necessary to build a self-driving fleet that could take on Uber. The company’s recent scale-back of Google Fiberis instructive in this regard: it is very difficult for a company built on search advertising margins to stomach the capital costs entailed in building out a fleet capable of challenging Uber in more than one or two markets.

Finally, as the incumbent in the transportation-as-a-service space Uber has the advantage of only needing to be good-enough. To the degree the company can build out UberPool and UberCommute, they can ensure that their own self-driving cars get first consideration from consumers trained to open their app whenever they are out and about.

Needless to say, the next few years will be fascinating to watch. The only sure thing is that the Uber-Google battle in particular will be quite the ride.

This article first appeared in www.stratechery.com