A Startup Is Testing the Subscription Model for Search Engines

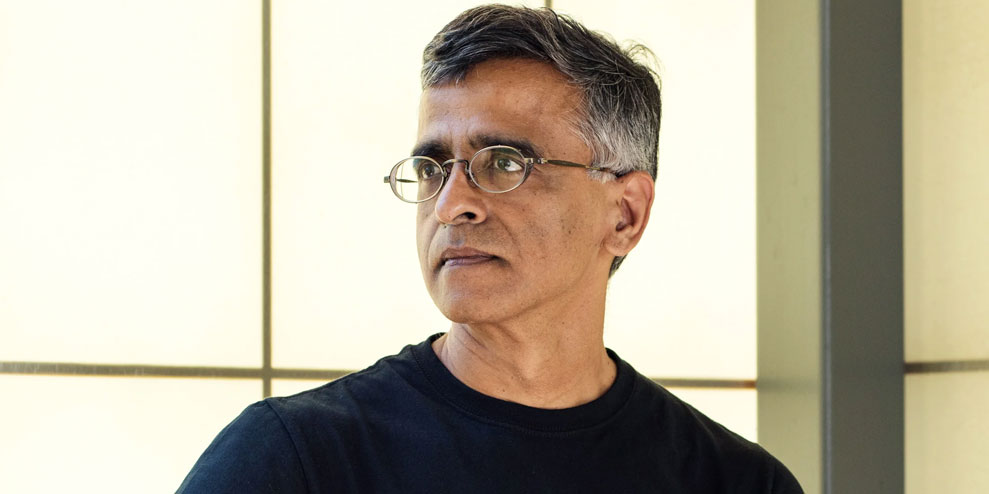

Sridhar Ramaswamy—the head of Google’s $95 billion advertising arm—left the company after a scandal concerning advertisements for major corporations found on YouTube videos that put children in questionable situations. Ramaswamy told The New York Times that shortly after that incident, he decided that he needed to do something different in his life—because “an ad-supported model had limitations.”

Ramaswamy’s startup company, Neeva, is that “something different”—and though it, too, is a search engine, it seeks to sidestep some of Google’s problems by avoiding the ads altogether. Ramaswamy says that the new engine won’t show ads and won’t collect or profit from user data—instead, it will charge its users a subscription fee.

Neeva’s approach follows an old truism that says if you pay for something, you’re a customer—but if you get it for free, you’re a product. That’s likely to be a difficult sell to a public that has come to expect “free” services and doesn’t often care very much about privacy aspects. Even if we hand-wave the difficulty of acquiring a market, other privacy-focused players are expressing significant doubt about Neeva’s approach.

Search engine DuckDuckGo is probably the best-known privacy-focused Google competitor. DuckDuckGo serves ads but doesn’t track its users individually. Its CEO, Gabriel Weinberg, says the ads are a practical necessity. “If you want the most impact to help the most people with privacy, you have to be free,” he said, “because Google will be free forever.”

However, DuckDuckGo may not be the most relevant comparison to Neeva. The new search engine is planned to be a second-tier provider, with public results sourced from Bing, Weather.com, Intrinio, and Apple. It also plans to offer its users the ability to link cloud accounts such as Google G Suite, Microsoft Office 365, and Dropbox. In addition to providing search results directly from these private sources, Neeva will include that data in building a profile to personalize search results for each user.

Startpage is a closer analogue to Neeva’s proposed model. Like Neeva, Startpage sources search results externally—in its case, directly from Google. Unlike Neeva, Startpage still shows Google ads and collects a cut of the proceeds. But it shows those ads without attempting to personalize them for the user—no profile is built, and the user’s potentially identifying information is stripped from the queries passed along to Google as well.

Startpage CEO Robert E. G. Beens reached out to Ars by email shortly after Neeva’s launch. He expressed extreme skepticism about Neeva’s model—he describes the connections to private data, personal profile building, and long-term data retention as “a hacker’s dream, and a user’s nightmare.” He expressed equally strong opinions about Neeva’s actual privacy policy, calling it “a joke—and not a funny one,” after remarking that “marketing messages can claim almost anything, but a privacy policy has legal status.”

We should note that there are two different sections of Neeva’s site that appear to address privacy concerns—a Digital Bill of Rights prominently featured in the company’s About page, and the official Privacy Policy, linked more austerely from the footer of each page.

Neeva’s Digital Bill of Rights appears to be just the sort of marketing message Beens alluded to. It makes lofty statements about users’ rights to privacy, controls on data collection, data usage transparency, and user ownership of their own data. It further declares that companies in general should respect those rights—but it makes no outright promises about whether or how Neeva will respect them. The closest thing to a concrete statement of policy on the page is a line at the bottom stating, “We at Neeva stand by [these values], in solidarity with you.”

Neeva’s Privacy Policy, in contrast, is a standard legal document, and it reads like one. It’s also much more concrete and lays out some troubling details that sound opposed to the lofty ideals expressed in Neeva’s Digital Bill of Rights. A section titled “Disclosing Your Information to Third Parties” even seems to contradict itself.

Although the “Service Providers” and “Advertising Partners” subsections are hedged with usage limitations, there are no such limits given for data shared with affiliates. The document also provides no concrete definition of who the term affiliates might refer to or in what context.

More security-conscious users should also be aware of Neeva’s data-retention policy, which simply states,”We store the personal information we receive as described in this Privacy Policy for as long as you use our Services or as necessary to fulfill the purposes for which it was collected … [including pursuit of]legitimate business purposes.”

Given that the data collection may include direct connection to a user’s primary Google or Microsoft email account, this might amount to a truly unsettling volume of personal data—data that is now vulnerable to compromise of Neeva’s services, as well as use or sale (particularly in the case of acquisition or merger) by Neeva itself.

Neeva is currently in limited beta testing and is not available for general use. Interested potential users can join a waiting list to become an early tester.

–

This article first appeared in www.wired.com

Seeking to build and grow your brand using the force of consumer insight, strategic foresight, creative disruption and technology prowess? Talk to us at +971 50 6254340 or mail: engage@groupisd.com or visit www.groupisd.com/story