We look at the winners of Fast Company’s Innovation by Design Awards over the past 10 years as a lens onto a broader shift toward sustainable design thinking.

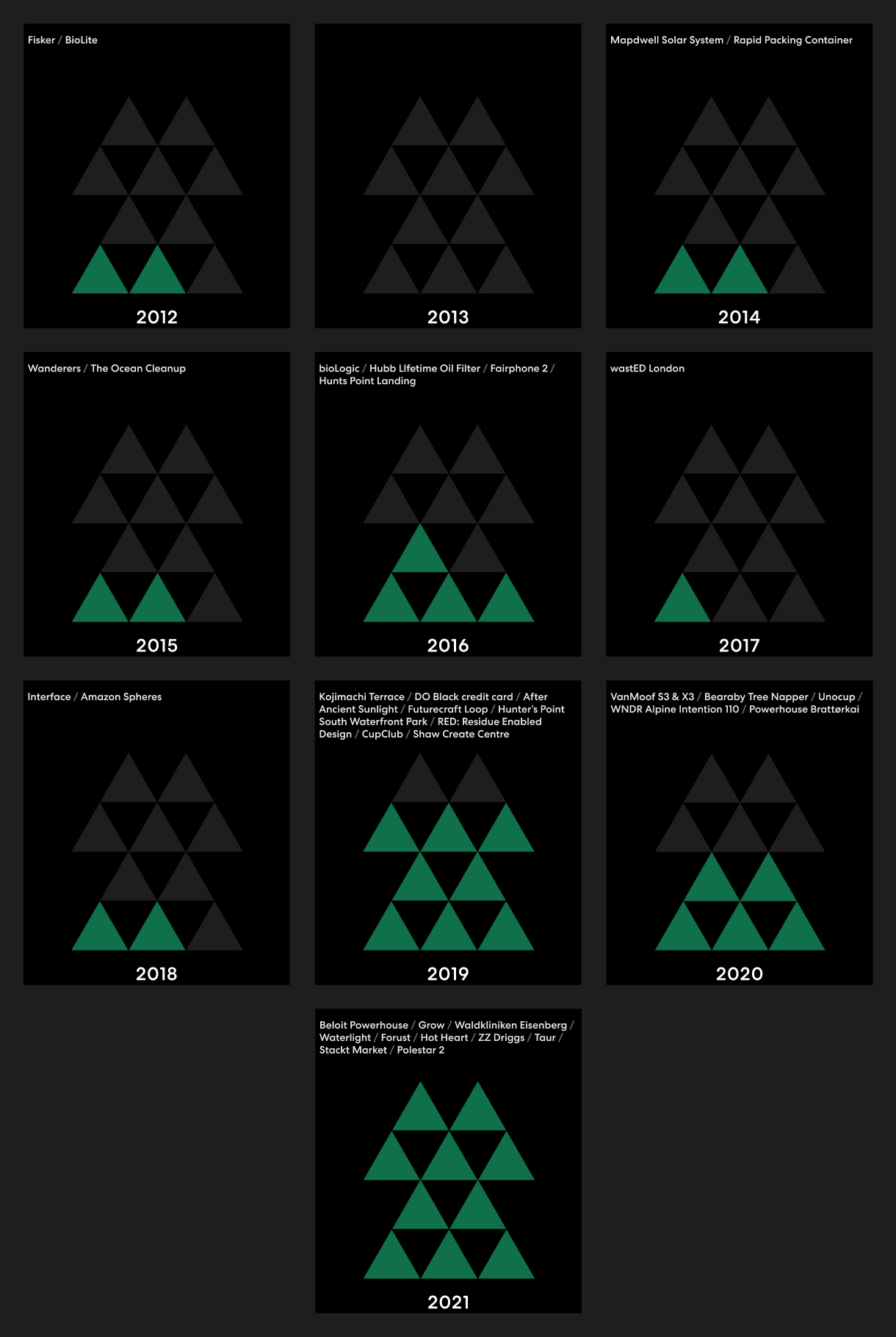

When Fast Company launched the Innovation by Design Awards in 2012 to honor creativity in business, just two of the winning entries embraced sustainability as a central design thesis.ADVERTISEMENT

This year, roughly a third of the winners prioritize the environment, ranging from a converted coal power plant to a device that transforms salt water into electricity. As the effects of climate change become increasingly visceral, spreading fires, hurricanes, and other disasters around the globe, design is becoming a crucial tool of adaptation. “Designing for human survival will become the new necessary field of design,” says Slow Factory Foundation founder Céline Semaan in a special Fast Company report on where the industry can have the greatest impact in the next decade.

In some ways, eco-friendliness has always been a key aspect of good design. Legendary industrial designer Dieter Rams declared it nearly 50 years ago, as one of his 10 principles of good design. But the parameters of what constitutes sustainable design have shifted over time. Is a plastic coffee maker that lasts 20 years, but ultimately ends up in a landfill, really sustainable? Today, many designers understand that every part of product development, from the materials used to a product’s afterlife, must be carefully considered to limit waste. Others have gone a step further and found creative ways to actively reuse waste. Forust, the winner of this year’s Innovation by Design Award in materials, uses 3D printing to turn sawdust into furniture, bowls, and other accessories. RED, the winner of 2019’s student Innovation by Design Award, explored using red mud, a waste product of aluminum manufacturing, to create gorgeous ceramics and building materials.

Some designs were simply ahead of their time. An early winner of Innovation by Design was the Fisker Karma, one of the world’s first luxury plug-in electric vehicles. It had a solar panel on its roof and sustainable materials inside, like trim made from salvaged wood. “The Fisker shows what you can do by taking risks in sedan design,” judge Erica Eden of Smart Design said at the time. Shortly thereafter, the company went out of business when its sole battery supplier filed for bankruptcy. Intriguingly, the Karma’s design ideas live on in this year’s winner of the products category, Polestar 2. An electric car spun out of Volvo’s skunkworks lab, it has seat backs crafted from old water bottles and carpet made from fishing nets. It also uses blockchain technology to trace the origin of its cobalt, a key component of lithium-ion batteries that is often mined to devastating effect on both people and the planet. Polestar’s investment in these features shows the long tail of bold design.

Many of the biggest strides in sustainable design over the past 10 years have come from architects. This may be a case of necessity breeding invention: Architecture and construction are responsible for nearly 40% of global CO2 emissions, an astonishing footprint for an industry that doesn’t garner nearly the attention of polluters like agriculture (representing 11% of global greenhouse gas emissions) and aviation (representing about 2%). Architects have responded with a range of thoughtful solutions, including offices that usher the outdoors in and buildings that generate more power than they consume, but adaptive reuse may be the profession’s most impactful legacy. It’s the idea that one of the greenest ways to build is to reuse what’s already there. In Long Island City in Queens, New York, the architecture firms SWA/Balsley and Weiss/Manfredi converted an abandoned industrial landscape into a 30-acre park that is designed to protect the area from rising flood waters. The project, called Hunter’s Point South Waterfront Park, was an Innovation by Design winner in 2019. Two years later, the Chicago architecture firm Studio Gang has won accolades for another adaptation of industrial space, the Beloit Powerhouse, which transformed a coal power plant into a gym and student center at Beloit College in Wisconsin.

Some areas of design still have a ways to go. Disposable goods remain far too common in retail, and fashion and tech companies are particularly guilty of flooding markets with planned obsolescence in mind. “After nearly 15 years, I am using my fourth iPhone,” Frog Design founder Hartmut Esslinger tells Fast Company in the special report on design’s future impact. “Each time I had to buy a new one because of CPU (central processing unit) performance, [and]I put otherwise perfectly functioning products into my closet.” He calls on designers to extend their thinking beyond products and services to the very economic forces underpinning their work. “Recycling is a good thing, but not enough,” he says. “Design must inspire a new economic model and deliver much more long-term solutions.”

…

This article first appeared in www.fastcompany.com

Seeking to build and grow your brand using the force of consumer insight, strategic foresight, creative disruption and technology prowess? Talk to us at +971 50 6254340 or mail: engage@groupisd.com or visit www.groupisd.com/story