After years of research, Formafantasma publishes a staggering multimedia documentary about the e-waste crisis.

In 2080, less than a generation from now, the world is on track to hit a crucial geological milestone. According to the Amsterdam-based designers Andrea Trimarchi and Simone Farresin, the largest metal reserves will no longer be below ground. They’ll be above it, embedded in smartphones, appliances, and other forms of wealth, which will “stream freely across the the surface of the planet–as if through a continuous, borderless continent.” Instead of mining ore from the earth, it will be “remined” from the millions of tons of e-waste that the world produces.

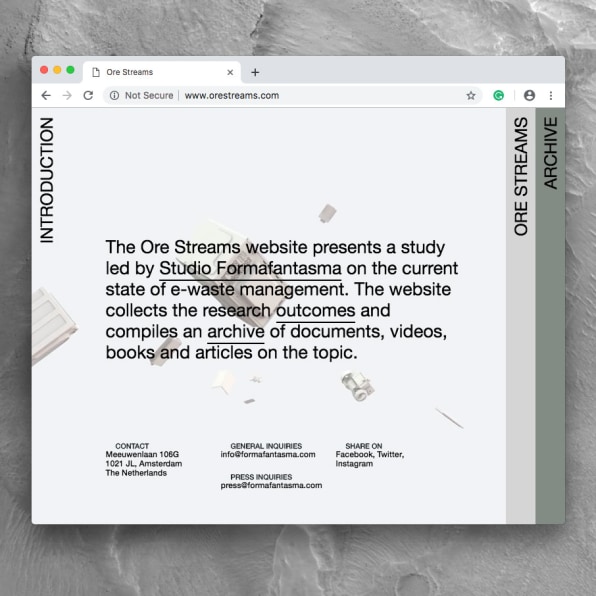

Trimarchi and Farresin, who run the studio Formafantasma, have spent the last few years reckoning with design’s role in the production of more and more objects and more and more waste. They’ve interviewed recyclers, activists, policymakers, and other experts. Supported by the National Gallery of Victoria and, more recently, MoMA senior curator Paola Antonelli, they’ve also produced a series of videos, visualizations, and physical objects based on their research.

The final result, called Ore Streams, made its debut last week at the Milan Triennale as part of the symposium and exhibition, Broken Nature: Design Takes on Human Survival. All of their research is available online as a media-rich website, too. “We believe it is important to share with others our findings and to offer the opportunity to appropriate our own research,” the founders say over email. “We did not envision this outcome at the beginning of the project. Nevertheless we felt the urgency to give more context to the work.”

It turns out that ore (a term for rock from which any valuable metal can be derived) can tell you a lot about how capitalism came to be. Ore Streams zeroes in on that unsettling history, tracing how design helped establish the immensely wasteful way products are manufactured, consumed, and discarded today.

The project’s centerpiece is a 25-minute visual essay that traces the colonial exploitation of indigenous peoples and their land for mining through to the emergence of capitalism, as tons of metal and other by-products made their way to Europe, enabling manufacturers to produce more and more consumer goods at less and less cost.

Today, the same countries that were brutally mined centuries ago are being “remined” as e-waste is exported from America and other countries back across their borders and then scavenged, often by young children, for their toxic but valuable embedded metals.

Tech companies are driving this process by developing components that are either proprietary, unfixable, or un-recyclable. As phones have gotten thinner, companies have started putting them together with glue instead of screws, further complicating recycling. The competition for thinner, better, and newer is heralding a second-coming of colonialism throughout the world, Ore Streams concludes. Thanks to e-waste, the process of colonial exploitation is repeating itself, the narrator explains: “Developing countries are exploited twice, first for raw materials, then for dumping grounds.”

Another Ore Streams video documents the history of planned obsolescence. The term was invented by economist Bernard London during the Great Depression, when London noticed that people were using their old shoes, furniture, and cars rather than buying replacements. His idea? Give these consumer goods an official lifespan, enforced by the government. “After the allotted time had expired, these things would be legally ‘dead,’” London wrote in 1932. People would be forced to buy new goods, buoying the economy.

London’s vision was slightly off, of course. It isn’t the government enforcing an expiration date on our things–it’s the companies that make them. Tech giants stop supporting older phones because they’ve “innovated” with new models. Smart appliances contain electronics that will eventually become outmoded, forcing people to buy new ones.

Ore Streams isn’t just a history lesson, though. The project contains specific recommendations–both for policymakers and companies but also designers and engineers, who are “ignorant of the complications they’re creating for the recycling process” with their work.

Another video illustrates the problem perfectly: It’s simply an hour-long overhead shot of e-waste recyclers attempting to disassemble iPhones, laptops, and fridges and laying out their components in a neat grid.

Trimarchi and Farresin clearly believe designers have the power to make products that last longer and are easier to recycle. “Design too many times is interpreted as a styling tool,” they say. “If designers operate within certain frameworks, [it’s] not necessarily because of their own choices.”

In a final video, they describe specific design strategies based on their years of research. For instance, designers could establish a universal standards for items like screws, which would make it easier to repair and recycle products that use them. They also need to educate themselves on current recycling processes before putting anything out into the world. Take glass components, which are prone to shattering and which automated recycling systems have a hard time recognizing. Or concrete mixed with iron, which separators typically incorrectly categorize.

Instead of using glue to put together products, designers need to create new clamping systems that are easier for recyclers to take apart. Another glaring need: a universal system of labeling toxic batteries to protect the people who have to take them apart. The list goes on.

After two years of research into recycling and waste, will Formafantasma itself change as a design studio? “The way we see our studio evolving after Ore Streams is in developing a more radical part of the studio,” the founders say, “where research-based projects will be conducted without any pressure to develop product-based outcomes.”

Each of the Ore Streams videos is well worth a watch. By the end, it’ll be hard to look at your phone or laptop the same way.

–

This article first appeared in www.fastcompany.com

Seeking to build and grow your brand using the force of consumer insight, strategic foresight, creative disruption and technology prowess? Talk to us at +9714 3867728 or mail: info@groupisd.com or visit www.groupisd.com