Ferrari’s cars are iconic, but the reasons why are more mysterious.

![[Photo: Luke Hayes]](https://images.fastcompany.net/image/upload/w_562)

You might never encounter a Ferrari in person in your entire life–let alone sit behind the wheel of one–yet you know exactly what the car symbolizes. Beauty, desire, luxury, excitement. What began in the 1940s as an eccentric man’s racing enterprise has since evolved into a lifestyle. You can buy hats, jackets, backpacks, and shoes emblazoned with Ferrari’s iconic prancing horse logo; visit theme parks where the roller coasters and go-carts riff on Ferrari Formula 1 race cars; read a magazine dedicated to the cult of Ferrari. How did Ferrari build such a salient brand?

“The branding and the reputation comes from the quality of the product,” says Andrew Nahum, a curator of Ferrari: Under the Skin, a new exhibition at the Design Museum, in London, that unpacks automaker’s legacy. “They can do that because the quality of the product and the continuity and history of it. It’s a super-car like no other, really.”

But a good product alone doesn’t create a legendary company. It’s a combination of vision, execution, and knowing how to cultivate a legacy while always looking forward.

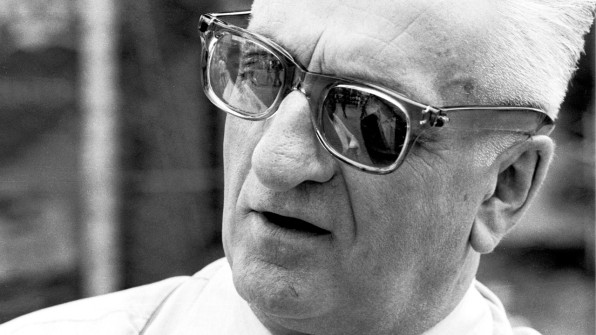

A FOUNDER LIKE NO OTHER

Enzo Ferrari founded his race car manufacturing outfit in 1947, but the company’s origin story starts years earlier. In 1929, Ferrari (who was 31 at the time and an established race car driver) founded Scuderia Ferrari, which bought and raced high-performance cars. He was always concerned with what would enable him to win. Eventually, he decided that to have an edge he’d have to build and design his cars from scratch, starting from the engine.

“His single-mindedness is purposeful and his intention to win races, above all else, is what made the company and drove its engineering objectives,” Nahum says.” Enzo was a charismatic, enigmatic, difficult, sometimes charming, and unique individual. The comparison he brings to mind is Steve Jobs. He was not a consensual manager. He wasn’t asking what people wanted him to do. He wasn’t doing market research. He was animated by his own sense and his own spirit. He was a creative in a way, though he didn’t do the designing himself. Like Steve Jobs, he had an ideal.”

This ideal was to build a high-performance machine and it began with the engine. “I don’t sell cars, I sell engines,” Ferrari once said. “The cars I throw in for free, since something has to hold the engine in.” The statement is hyperbole since the design of Ferrari’s auto bodies is instrumental in how the car drives.

SCIENCE MEETS SCULPTURE

There’s an unmistakable look to Ferarri’s cars today, and every contour serves a deliberate, purposeful function to route air around the car and improve performance. The designers are looking for ways to push the car to the ground and make it more stable.

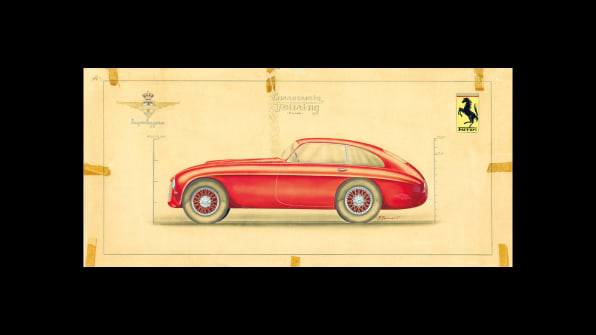

In 1951, Ferrari enlisted the Turin-based auto body manufacturer Pininfarina to build his cars, which employed an architectural approach to how it sketched its designs. The draftsmen would draw cross sections and elevations for the cars–the shape of which was based on aerodynamics–then send those specifications to modelers to create full-scale mock-ups of the cars in wood. Over the years, Pininfarina changed the material it uses to mock up the cars, transitioning to metal and wire frames to plaster to foam and now clay. The designers today sketch and draw using digital tools, but they always make clay models.

celebrate Scuderia’s fourth year

“[Ferrari] says there’s something not quite there when [a design]comes straight from the computer,” Nahum says. “The sculptural unit of the car is absolutely important, they pay great attention to that.The car modelers typically mock up a new design in clay based on the designers’ drawings. Then the designers inspect it and offer feedback on the aesthetics. “It’s an emotional reaction–it looks too muscular, it looks too mean, it looks too hollow,” Nahum says. The modelers then correct the silhouette in clay until it reaches the right look.

“It’s a subtle and internalized process,” Nahum says. “If you ask a designer what they’re doing, they’ll say it has to look like a Ferrari but it mustn’t quote from the past in a cliched way. They’re inspired by the past, but they don’t say, ‘Well the 250 GTO was wonderful, let’s do that again.’ Or, ‘That kicked-up rear spoiler is really classic, we’ll try that.’”

CULTIVATING A LEGACY

That dialogue with the past is a key part of Ferrari’s branding strategy. “What’s striking to me is that Ferrari and its approach today really have continuity with Enzo Ferrari and his ambition and personality,” Nahum says. “There are a number of extraordinary high-performance cars around with extraordinary capability, but they don’t go back to 1947 with an unbroken lineage of outstanding cars.”

When Nahum was conducting research for this exhibition, he found that Enzo Ferrari was always very particular about how his brand was represented. For example, he kept a tight rein on his prancing horse logo. It was originally the personal symbol of a fighter pilot. After the pilot died in a crash, his family permitted Enzo to use it for his enterprises.

“Ferrari had a highly considered view of his company right from the start,” Nahum says. “There’s an amusing anecdote about a salami manufacturer nearby who tried to use a prancing pig as a trademark. Ferrari sued because he thought it was ridiculing the prancing horse, and he won.”

He applied his logo–which he modified to include a yellow background, the official color of Modena–to all of his cars. He also put the logo on an annual yearbook Ferrari published and on products–like watches–that he would give as gifts to friends. Branded merch is common today, but it wasn’t during Enzo Ferrari’s time.

The manufacturer and lifestyle brand we know has evolved beyond its start as a scrappy racing outfit from a racing enthusiast, and there are dozens more stories about how Ferrari’s design language and ethos helped turn it into the leviathan it is today. Nahum hopes the exhibition–which includes actual cars, video, sketches, archival photographs, and new interviews with present-day leadership–helps Ferrari fans learn more about the design and process behind their favorite cars. He also hopes design enthusiasts earn an appreciation for automotive design–a field that doesn’t receive the credit it deserves, Nahum believes. “It’s the translation of art into engineering,” he says.

–

LaFerrari, 2013. [Photo: courtesy Ferrari]

[Photo: Luke Hayes]

This article first appeared in www.fastcodesign.com

Seeking to build and grow your brand using the force of consumer insight, strategic foresight, creative disruption and technology prowess? Talk to us at +9714 3867728 or mail: info@groupisd.com or visit www.groupisd.com