The surprising story of the Google gambit that stripped Google+ of some of its best features—and turned them into a photo app that’s become a blockbuster.

In a tech industry obsessed with scale, no aspiration is more iconic than building something that reaches a billion users. And nobody has achieved it more often than Google. Eight of its products have hit that enviable milestone: Android, Chrome, Gmail, Google Drive, Google Maps, the Google Play store, YouTube, and, of course, its namesake search engine.

Make that nine. The company is announcing that Google Photos has crossed the billion-user threshold. It crossed the line earlier this summer, a little over four years after its debut at the Google I/O conference in May 2015. Gmail took a dozen years to hit a billion users; Facebook and Instagram, about eight years apiece. Which makes Google Photos’ growth spurt not only impressive, but unusually rapid.

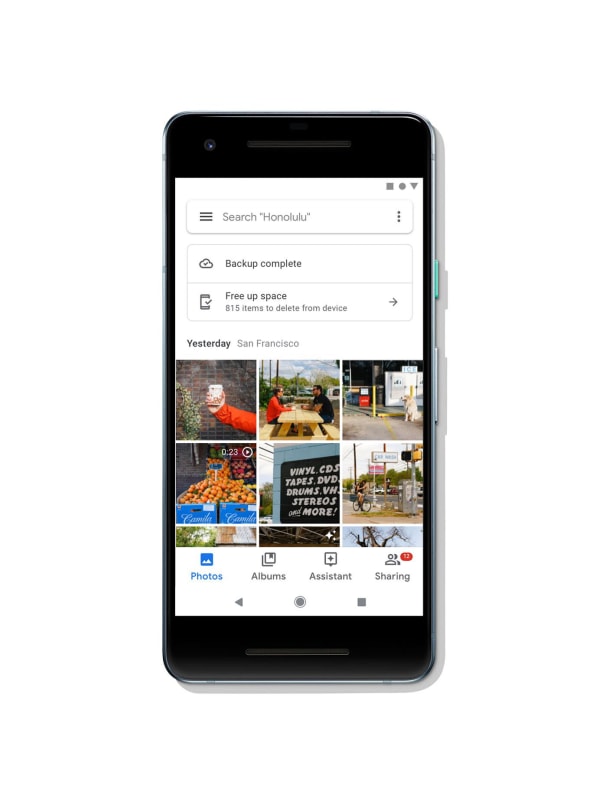

The app has certainly had some factors working in its favor. Google Photos ships preinstalled on Android phones, a powerful mechanism for getting it in front of vast quantities of new users. It’s also available on the web and as one of Google’s best apps for the iPhone and iPad. And it offers unlimited free storage—as long as you’re okay with having your photos and videos compressed using Google’s optimization algorithm—making it one of the web’s most tempting freebies.

Still, Google Photos’ success was hardly preordained. The app is a spin-off from Google+, the social network otherwise known primarily for never having put a dent in Facebook’s hegemony. (Google shuttered the consumer version in April.) Once spun out, it arrived years after other tools for storing, organizing, and sharing photos; Google even had another one of its own, Picasa, which it acquired back in 2004 at the same time that Flickr was taking off. Even now, Photos often isn’t the default photo app on Android phones: Samsung’s Galaxy models, for instance, emphasize their own Gallery app, with Photos squirreled away in a “Google” folder.Anil Sabharwal, the Google VP who led the creation of Google Photos, credits several factors for its success. In 2015, when it launched, the timing was finally right for Google to deploy a service that applied AI to billions of photos stored in the cloud. And the company built something that users could trust to take good care of their images. “We have this insane responsibility,” he says. “These are people’s most important memories.”

Perhaps more than any other Google product of recent years, Photos has benefited from the company getting everything right—which, for a service borne of Google+, feels like a little miracle.

FROM APPS TO HANGOUTS TO PHOTOS

Anil Sabharwal grew up in Montreal, earned a degree in mathematics from the University of Waterloo, and eventually relocated to Sydney. He had spent most of his career at startups when Google tried to recruit him in the summer of 2008. At first, the notion of working at an enormous company did not speak to him: “I thought to myself, This is probably not where I want to be,” he says.

Google proved persistent, and Sabharwal ended up joining the company in January 2009. He worked on Google Apps—now known as G Suite—and helped build some of Google’s first truly native apps for iOS and Android. Four years into his Google tenure, he moved over to a project that the company considered at the time to be of utmost importance: the Google+ social network.

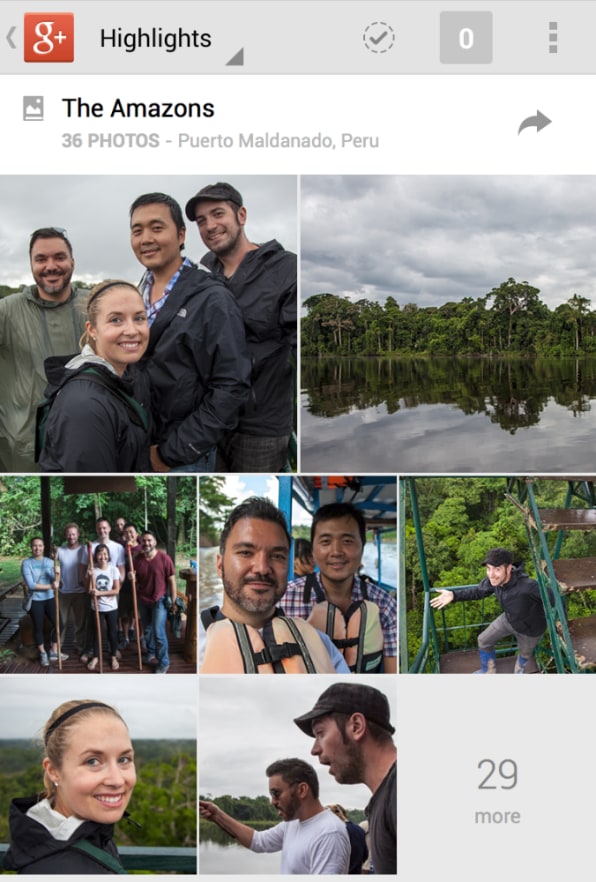

At first, Sabharwal was responsible for Hangouts, Google+’s video-calling feature. After six months, he moved over to the service’s photo-sharing capabilities. They had recently received an impressive AI-infused upgrade—here I am praising it at the time—but Sabharwal concluded that his first responsibility was answering an existential question: What, exactly, should Google+ Photos be?

That, he concluded, would require defining a three-pronged mission. “We needed to be solving a very clear problem for end users that currently is unsolved,” he explains. It had to be something that played to Google’s strengths. And the company would have to be as serious about the user experience as the underlying technology.

By any objective standard, Google+’s photo features were already slicker and more advanced than those on Facebook, which—except for facial recognition, in use since 2010—remained mundane at best. It didn’t matter. The most glorious possible photo-sharing tools didn’t mean much if all the people you wanted to share photos with were off on some other social network.

Rather than trying to improve on existing ways of sharing photos, Sabharwal became intrigued by a different task: simply managing them, whether or not you wanted anyone else to have a peek. It had become an increasingly unmanageable task in the smartphone era. “We used to get rolls of 24 frames of film, and we’d go and take 24 photos,” he says. “We now take 24 photos of the plate of food in front of us at a restaurant.” People with vast collections of images needed somewhere to store them, safely and privately. They also needed help finding the most important ones.

With its core competencies in AI, search, and cloud storage, Google was well-positioned to wrangle photo libraries. The challenge also satisfied Sabharwal’s unsolved-problem mandate. Both Facebook’s own photo-sharing features and Instagram were social to their core. Apple’s photo features for iPhones, iPads, and Macs were private, but they existed within that company’s walled garden and, at the time, were relatively spartan. Over at Yahoo, Flickr had only recently begun awakening from a long slumber.

Sabharwal’s exploration of what Google+ Photos should be had led him to a stark conclusion: It shouldn’t be part of Google+. Instead, he believed, it could stand on its own as a photo app that was first about helping people preserve, organize, and enjoy their own images, and only secondarily about sharing them with others.

By then, founding Google+ chief Vic Gundotra had left the company. Sabharwal refined the new vision with two other Google+ leaders, Bradley Horowitz and Dave Besbris. But the moment of truth came when he made his case to Sundar Pichai—at the time, the company’s product honcho, not yet its CEO. After Sabharwal presented his plan at a review meeting, Pichai “said, ‘Yes, this is the product we should build,’” says Sabharwal, who had first worked with Pichai years earlier on Google Apps. “He was a firm believer, of course, in machine learning and AI being the future of Google. And he said that’s where we needed to lean into.”Most of the Googlers on Sabharwal’s team agreed that abandoning the Google+ ship made sense. They included David Lieb, who had launched a private photo-sharing app called Flock before his startup, Bump, was acquired by Google. “The opportunity that we saw ahead of us in the social-sharing space just seemed less like a real problem that people were facing,” says Lieb, who became product lead for Google Photos. “It was more of a better version of something that people were already doing.”

Not everyone bought into the new direction. According to Sabharwal, the skeptics believed that spinning out Photos robbed Google+ of a critical competitive advantage it its war against Facebook. “We had a number of people who chose to leave the team,” he says. “I was a big believer in this idea of ‘This is where the bus is going. I need you to be either on or off the bus.’”

Sabharwal had an unusual degree of freedom to steer the bus as he saw fit. Though his title at the time—director, Google Photos—wasn’t especially lofty, Google granted him sprawling responsibility for the project across product, design, and engineering. “At my level, across the company, that was incredibly unusual,” he says. Normally, if product and engineering teams reported up into one person, it was someone at a rarified senior-VP level, creating willful tension between different interest groups.

The fact that Google Photos could repurpose functionality built for Google+ at will helped. “Along the way, the team had actually developed a lot of really good underpinning technologies that also applied to private photo management—things like automatic backup,” says Lieb. Google+ also provided the basis of Google Photos’ AI-assisted search features, which, with their ability to find specific people, locations, and photos associated with concepts such as “garden” or “airplane,” are often downright uncanny.

But Google couldn’t just saw off Google+ Photos into a stand-alone app and rush it out the door. “If I take a photo of a receipt, it’s unlikely I’m going to use it in a social networking capacity,” says Sabharwal by way of example. “But in a gallery, it’s incredibly important that it’s the first photo at the top.” Users tended to accept the fact that a social app like Google+ required robust internet access to function; they would not be so forgiving if a balky connection prevented them from seeing their own photo library.

Though it took time to work out the details, Sabharwal’s team members were confident that they knew what users would want. “A lot of us ended up managing our whole family’s photo collections for various reasons and backing them up,” says Leslie Ikemoto, who worked at first on the Photos app for iOS and is now machine intelligence lead. “And so I think we kind of understood the pain.” But they aspired to go well beyond a baseline set of features. They believed that today’s nerdy edge cases are tomorrow’s mainstream necessities—a Google strategy dating back at least as far as the birth of Gmail, which 1 GB of storage initially struck some outsiders as more of a prank than a pressing innovation.

“We decided, let’s just go solve all these problems that we ourselves were starting to face, and that we believed the rest of the world would start to face over the subsequent years,” explains Lieb.

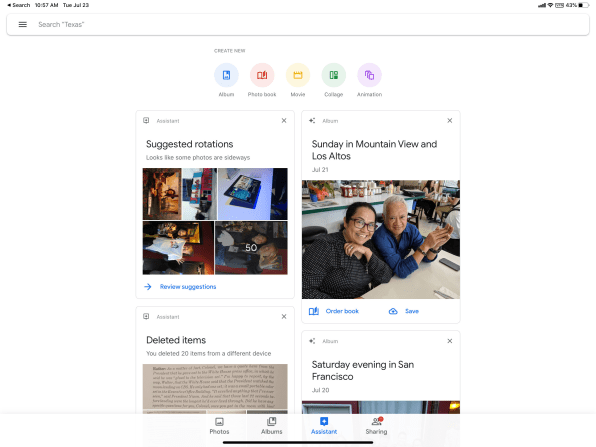

The Assistant—which uses AI to proactively perform an array of tasks, from creating collages and mini-movies to finding photos you might want to delete—became a signature Google Photos feature. It grew out of Lieb’s fanciful vision of giving users something that felt like a clone of themselves dedicated full-time to photo management. As Sabharwal remembers Lieb asking: “What if I could take you and I could shrink you and I could put you inside your own phone?” (Another influence: the Scarlett Johansson-voiced AI assistant in Spike Jonze’s film Her.)

One thing the Google Photos team didn’t do for their brainchild was to formulate a business model that would make it a cash cow. Sabharwal points to two revenue streams: Users can pay for additional storage (which they’ll need only if they want to save images without putting them through Google’s compression scheme) and printed-on-paper photo books. On top of that, any loyal Photos user will be drawn more deeply into the Google ecosystem, a boon for the company as it rolls out products such as the Nest Home Max smart screen. (Among other things, it’s a Google Photos-powered digital picture frame.)

However, Google steered clear of an opportunity for profit that might pop into many heads as a Google-y thing to do: mining photos for data that would let it display targeted advertising or otherwise monetize users. It’s a particularly sensitive subject given the service’s emphasis on privacy. From the start, there were “absolutely no plans for us to do anything with ads related to that content, because they’re very private and personal moments,” stresses Sabharwal.

THE CLOCK TICKS

Originally, Google had hoped to launch Google Photos by the end of 2014. Routine schedule slippage pushed the target into early 2015. After a well-received demo during a board meeting—”Eric Schmidt pulled me aside and said, ‘How can I help?” remembers Sabharwal—a March release felt eminently doable.

There was just one catch. Pichai was so enthusiastic about Photos that he wanted to make it one of the key announcements during the company’s Google I/O conference in May. That would mean pushing the unveiling out a couple of months, an act of deferred gratification that sounded unbearable to Sabharwal.

“I said, ‘Please, no—I have pushed this team like crazy for the last nine months,” he remembers. “We’re ready to launch. They all want a launch. And if I delay this timeline, the team is not going to be very happy with me.”

Pichai was unswayed. But he did agree to personally defend the move to Sabharwal’s reports. “He got in front of the entire team,” says Sabharwal. “And he said, ‘Listen, what you’ve built is really, truly magical. It’s a great example of using machine learning to solve a really important problem for our end users. Trust me. We’re going to launch this at I/O, and after that happens, you are going to thank me.’”

Hello world #io15 pic.twitter.com/tRWneHhE8K

— Google Photos (@googlephotos) May 28, 2015

During Google’s I/O keynote on May 28, Sabharwal and Lieb appeared onstage to introduce Google Photos, snapping a selfie of themselves to show off what you could do with the service. News coverage and first-look reviews were uniformly positive and sometimes even giddy—not always the case for a new Google offering—with various outlets calling the app “magical,” “brilliant,” and “essential.”

More important, consumers embraced Google Photos at the sort of scale the company craves. In its first five months, it racked up 100 million monthly users. For the app’s first anniversary, Google announced the head count had reached 200 million. A year after that, it was at half a billion.

Google has kept that growing user base engaged with a steady flow of new capabilities. Many of them involve sharing photos—but with a more intelligent, intimate feel than anything in Facebook. Partner Accounts, for example, let you automatically share photos that show specific people with a confidante. “I’ll be sitting here and my phone will buzz because my wife took a photo of our kids back in Australia,” says Sabharwal. It’s his single favorite Google Photos feature.

BEYOND THE FIRST BILLION

Four years after Google Photos launched, Sabharwal is proud that its original vision doesn’t just remain popular with consumers; it’s proven a durable way to get everyone on the team marching in the same direction. “If you walk through the Google Photos building and you say, ‘Hey, what do we do?,’ every single person will say to you, ‘We are a home for all your photos, organized and brought to life so you can save and share what matters,’” he says, repeating the mantra he recited during the 2015 I/O keynote. That clarity of mission, he adds, “helps us make decisions. It helps us break ties.”

Its effectiveness in the case of Google Photos also provided a boost to Sabharwal’s career. After five years at the Googleplex in Mountain View, he returned to Sydney, where he now manages Chrome and Chrome OS; he also spent 18 months supervising communications offerings such as Google Fi and Duo. Though Photos remains in his purview, he has handed off day-to-day oversight to general manager Shimrit Ben-Yair, a 10-year Google veteran whose past includes work on YouTube and other services.

Ben-Yair, Lieb, and others responsible for Google Photos still have a long to-do list. “When we first started working on this, I and some others started to write down the spec for Google Photos,” says Lieb. “It turned out to be like a fifty-page document, all the stuff that we wanted to build. And here we are, four years after launch, and we’re still finishing up some of this stuff that was on that first list. And along the way, we’ve doubled or tripled that list of [desired]features.”

The Google Photos team’s most immediate news, however, isn’t about an upgrade to Google Photos. At an event called “Google for Nigeria,” the company is announcing Gallery Go, a streamlined sibling designed for Android Go, the version of Android meant for consumers in developing markets.

Like Android Go itself, Gallery Go is engineered to run smoothly on low-cost phones that may have less-than-copious access to high-speed data. It leaves out the advanced Assistant features in favor of focusing on zippy photo viewing, essential editing tools, and auto-enhancements. “You have to be really thoughtful about memory and how you manage network usage and all these things,” says Ikemoto. “From the engineering side, that’s super interesting.”

The ultimate goal of the new app is, of course, still more growth. “We’ve crossed this really critical milestone of a billion monthly users, and Gallery Go is how we think about the next billion,” says Sabharwal, who calls the desire to preserve and share photos universal. Even if it now requires two apps to express it, Google Photos’ founding vision is nowhere near maxed out.

–

This article first appeared in www.fastcompany.com

Seeking to build and grow your brand using the force of consumer insight, strategic foresight, creative disruption and technology prowess? Talk to us at +9714 3867728 or mail: info@groupisd.com or visit www.groupisd.com