For the first piece in our series How CEOs Write, we talked about how Tesla’s missteps and failures can be traced back to three critical mistakes that Elon Musk makes in his writing, tweeting, and emails. Check it out here.

There’s probably no technology company that values the written word and produces written output quite as much as Amazon.

At Amazon, meetings to present ideas start not with PowerPoint slides but with narratively structured memos.

Years have proverbial themes—like the Year of Getting Our House In Order—that guide the Amazon’s priorities and decision-making for that year.

And every year, the company’s chief executive, Jeff Bezos, writes a long annual letter to his shareholders—the only such investor letter, besides Warren Buffett’s letters for Berkshire Hathaway, to take on official “must read” status for not just Silicon Valley but Wall Street as well.

Bezos is Amazon’s chief writing evangelist, and his advocacy for the art of long-form writing as a motivational tool and idea-generation technique has been ordering how people think and work at Amazon for the last two decades—most importantly, in how the company creates new ideas, how it shares them, and how it gets support for them from the wider world.

Creating Good Ideas: Clear Thinking Is Clear Writing

At Amazon, instead of asking his senior leaders to brainstorm great ideas for the company, Bezos asks them to submit six-page, dense, narratively structured memos.

Writing memos forces his team to think through their ideas in high-resolution detail. Instead of wasting time with impromptu brainstorming sessions, writing memos ensures that group discussion is based on the critical review of the relevant ideas, not on hypotheticals.

Most importantly, it makes it impossible to hide any logical inconsistencies in the ideas that people put out there. By imposing a rigorous, standardized template on the process of idea generation at Amazon, Jeff Bezos raises the bar and raises the quality of his team’s thinking.

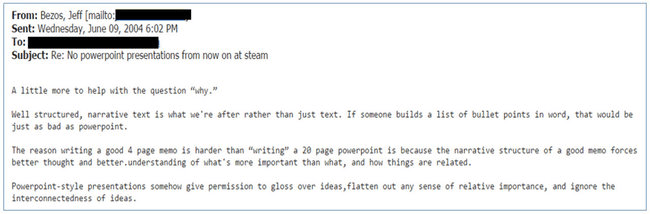

The email in which Jeff Bezos officially banned the use of PowerPoint at Amazon and insisted that people with ideas come to meetings with “well structured, narrative text.”

Bezos’s obsession with memo writing became law at Amazon on June 9, 2004.

In the now-famous email, he explained that no Amazon team members would be allowed to bring PowerPoint presentations or even lists of bullet points as documentation for meetings: all ideas were to emerge from densely written, narrative memos:

“The reason writing a good 4 page memo is harder than ‘writing’ a 20 page powerpoint is because the narrative structure of a good memo forces better thought and better understanding of what’s more important than what, and how things are related,” he writes, “Powerpoint-style presentations somehow give permission to gloss over ideas, flatten out any sense of relative importance, and ignore the interconnectedness of ideas.”

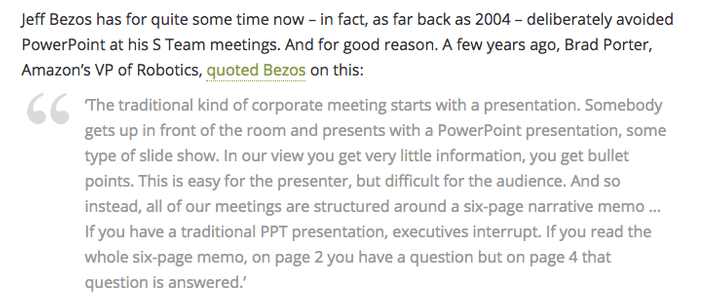

The memo-style of presentation is designed—contra forms like PowerPoint—to make presenting new ideas difficult for the presenter but easier for their audience.

Businesses need a repeatable process that helps generate good ideas consistently. Many companies do this by brainstorming—holding meetings for all involved to kick in ideas as a way to spur creativity by getting a diverse set of minds together.

But research has shown not only that humans are better at thinking creatively as individuals rather than as groups but also that inviting criticism and analysis is beneficial to creativity—not harmful, as some brainstorming advocates would claim.

A 2003 experiment at the University of California–Berkeley, conducted by Charlan Nemeth, set out to examine the effects of different kinds of group idea generation on idea creativity. One group was asked to answer a problem with no other instructions; one group was asked to brainstorm, with no criticism of others’ ideas allowed; and one group was asked to debate one another. The last group outperformed the other two by a significant margin when it came to coming up with diverse solutions.

At Amazon, the memo format allows every meeting where ideas are presented to turn into a deep debate of the idea’s relative costs and merits. This kind of criticism is even built into the memos themselves. Each memo is designed to be a full logical argument, complete with a reflexive defense of potential objections:

- The point or the objective being discussed

- How teams have attempted to handle this issue in the past

- How the presenter’s attempt differs

- Why Amazon should care (i.e., what’s in it for the company?)

If you’ve ever been in a brainstorm meeting, you’ve probably noticed that a few people can dominate the conversation. The nature of the format rewards quantity over quality and breadth over depth. The result is a lot of ideas from a few people that were all thought of more or less on a whim, many of which might not withstand even the slightest scrutiny.

Amazon involves the group, but only once the ideas are out there. Research tells us that while individuals are better at developing ideas, groups are much more efficient than individuals at recognizing the best ideas and figuring out how to implement them.

Often, the even bigger challenge, once the group figures out that they want to implement an idea, is getting that idea to spread among the wider team. Writing a six-page memo and thinking through every dimension of a new idea for the company is one thing; getting everyone in a company of hundreds of thousands to understand and live that idea is a different kind of problem entirely.

Spreading Good Ideas: Amazon Original Proverbs

Inside Amazon, Jeff Bezos’s use of proverbs to get his entire company aligned behind goals is legendary.

By packaging his ideas about how Amazon should work into short, simple, and easy-to-remember phrases—“It is always Day 1,” “process as proxy,” “high-velocity decision making,” and others—Bezos ensures that his ideas not only spread and get understood but also become an influential part of how people actually act inside Amazon.

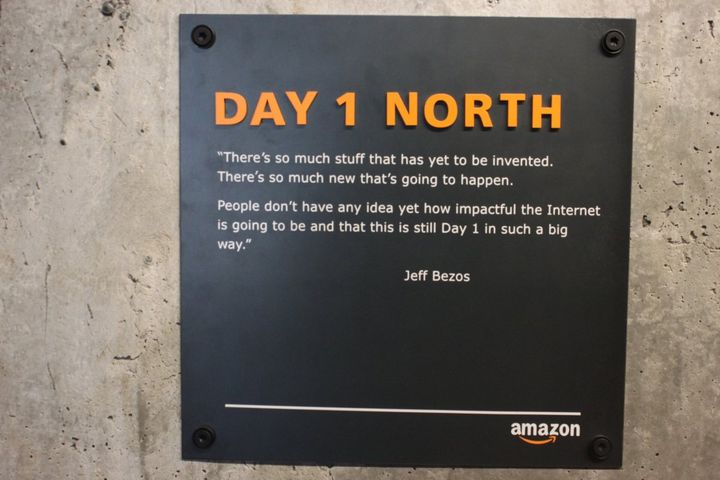

The “Day 1” metaphor first appears in one of Jeff Bezos’s first shareholder letters—it was so influential inside Amazon that at Amazon’s new Seattle HQ, Bezos named the building that he worked in “Day 1.”

Getting employees at all levels and in all departments on the same page often poses a difficult problem for senior leadership in companies. Messages get ignored or diluted and obscured as they pass from person to person and team to team. Instead of having a unified direction, the company then ends up with different departments prioritizing different things for different reasons.

All CEOs have to repeat themselves. But with the right kind of writing, you can improve comprehension and reduce the amount of time you have to spend explaining yourself. (Source: Lighthouse)

Packaging a message into pithy, aphoristic form is not only likely to make it more memorable; it’s also likely to make it more powerful. It’s less likely to be miscommunicated as it spreads from person to person, and it’s more likely to encourage the kinds of behaviors you want it to encourage.

At Amazon, the year that the company first approached $1 billion in revenue was the year they chose to title “Getting Our House In Order,” or GOHIO.

Being concerned that Amazons processes wouldn’t hold up to the pressure of the projected increase in volume they expected that year, Bezos knew that the focus of the company had to be on improving internal structure and process.

[source]

GOHIO became the pithy, memorable calling card of that entire year: a constant reminder that, as the company grew, everyone needed to be thinking about how the company would handle the increased scale of customer service complaints, web traffic, logistics issues, and more.

But probably the most influential proverb inside Amazon is the idea of Day 1.

Jeff Bezos’s first annual shareholder letter as CEO of Amazon, sent at the end of 1997.

Jeff Bezos’s 2016 annual shareholder letter, revisiting the idea of Day 1 and expanding on it.

The most important message a CEO needs to spread throughout a company is about culture: what types of mind-sets are valued, and what types of behaviors are encouraged. At Amazon, the entire cultural code is communicated in a two-word phrase: “Day 1.”

For Bezos, “Day 1” harks back to the first years of Amazon, when it truly was “Day 1” for the internet. With the internet age just beginning in earnest, Bezos knew Amazon was at an exciting juncture. There were no established playbooks for success on the internet. There were few successes to point to at all. All the company could do was try to deliver as much value as possible to their customers. Bezos’s instinct was that focusing on that, over the long term, would bring about the best possible results.

In his 2016 letter to shareholders, Bezos reviewed some of the forces that could lead a company to forget that it was in “Day 1” and lose that customer-centricity, and discussed how Amazon has held those forces off. In it, he expounds at length about what Day 1 still means to Amazon—customer-centricity, resisting proxies, always looking for ways to deliver values to customers.

Few memes can guide an organization’s thinking and behavior for nearly two decades straight. The only ideas that can survive for that long are the ones that are packaged memorably enough—and memorably packaging his ideas in just a few choice words has long been one of Bezos’s strengths.

It’s a strength that, clearly, he’s used not just internally but also in his communications with the public—and most importantly, with the public shareholders of Amazon Inc.

Getting Support for Good Ideas: The Language of a Leader

Bezos’s main form of communication with Amazon’s shareholders and customers comes in the form of an annual letter. In these letters, Bezos explains Amazon’s year, talks about what the company has learned and been challenged with, and gives hints about the future.

One reason Bezos’s letters are interesting is that, for the majority of its life as a public company, Amazon was not the darling of Wall Street, as it is today. For much of its lifetime, Amazon has been criticized for refusing to turn a profit, for being too ambitious, for spreading itself too thin, and for various other reasons. In his letters, Bezos hasn’t shied away from his critics—ironically, by addressing his critics head-on and at times professing his controversial decisions as Amazon’s chief executive, he has built up more trust among the true believers in his shareholder pool and removed doubters.

From Bezos’s first shareholder letter in 1997.

In his first public letter to shareholders, Bezos outright told his new investors that he would “make investment decisions in light of long-term market leadership considerations rather than short-term profitability considerations or short-term Wall Street reactions.” For tech-crazy shareholders in the late ’90s hoping to see exponential, immediate returns on their new stock investment, this wasn’t the most reassuring message to hear. And Amazon wasn’t struggling by any means—by that point, the company was already generating about $148 million a year in revenue and had grown by 838% year over year. Many Wall Street analysts bucked at this clear defiance of shareholders’ supposed supremacy, but Bezos was confident that the gains Amazon would make from a long-term strategy would far eclipse the losses from a few Wall Street speculators selling the stock early.

Another habit of Bezos throughout his shareholder letters is not holding back about his and Amazon’s failures, and professing that Amazon would keep seeking out opportunities to boldly experiment regardless of how many failures they faced.

In his very first letter he wrote, “We will make bold rather than timid investment decisions where we see a sufficient probability of gaining market leadership advantages. Some of these investments will pay off, others will not.” In his 2017 letter, Bezos acknowledged the ”billions of dollars’ worth of failures” they’d had ”along the way”.

The shareholders who balked at this strategy, thanks to this letter, had the opportunity to leave the company behind—but those who chose to stick it out and hold on ultimately benefited.

Part of it is Bezos’s style and his use of language—cool, calculated, and logically articulate. Like an air traffic controller talking down a scared pilot, Bezos doesn’t shy away from discussing disaster and failure and explaining his controversial ideas for how to run a company. Instead, he explains them thoughtfully and makes you understand from his point of view.

It’s also not uncommon to find Bezos strengthening and moving his points forward by posing questions to himself that a skeptical reader might bring up. In mirroring and then addressing readers’ concerns, Bezos makes the tone of his writing all the more calm and confident by showing that he knows the issue inside and out and can refute any doubts.

The question Bezos poses in the introduction of his 2015 letter, “Is it only coincidence that two such dissimilar offerings grew so quickly under one roof?” challenges the assumption upon which his previous point was supported: that the success of Amazon and Amazon Web services was by design rather than coincidence. The act of posing the question in itself indicates that Bezos has thought deeply about the information and is confident in what he is saying.

How Amazon Really Wins

Amazon and Jeff Bezos have become reference points for business leaders of all types looking for guidance on how to create and manage an innovative company. While CEOs and managers are quick to adopt Bezos’s ideas and put his best practices to work, few are likely to adopt the most influential and important practice inside Amazon itself: writing.

It’s not exciting or sexy, but as Jeff Bezos and Amazon have proved over the last two decades, the same skills involved in writing clearly, logically, and memorably are the same kinds of skills needed to build a company that is constantly able to deliver value to customers and reinvent itself.

–

This article first appeared in www.slab.com

Seeking to build and grow your brand using the force of consumer insight, strategic foresight, creative disruption and technology prowess? Talk to us at +9714 3867728 or mail: info@groupisd.com or visit www.groupisd.com