Air Jordans changed the sneaker business forever

Say you were a city kid growing up in America. Say you wanted to show off your grace and speed, your skills and creativity, your vision and stroke and raw power. You wanted to break laws and defy gravity. But you needed ankle support, and it was helpful to not burn the hell out of your soles. A good basketball sneaker mattered.

In 1923 Converse put the name of one of their salesmen, a balding white guy called Charles “Chuck” Taylor, on the side of a sneaker, but the Seventies saw corporate America finally acknowledge urban influence, the city game. Black players started getting paid to endorse basketball shoes: first Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, jazz fluid and unstoppable, with his picture on the tongue of an Adidas high-top; then Knicks guard Walt Frazier rocking low-top suede Pumas; then high-flying, superbly Afroed, ferociously goateed Julius Erving, who wore leather Converses with dr. j printed above the outsoles. Most sneakers of the era looked similar: leather or canvas or mesh, some with ankle support, always a layer of colored, vulcanized rubber for the sole. Nevertheless, your kicks announced your style, the fact that you belonged to a particular world, or at least that you wanted to belong.

In 1982, Nike introduced a leather high-top with a sole whose thickness and cushioning were unprecedented in a basketball shoe. The company called it an Air Force 1 and put a little strap around the high ankle. It looked like a boot you’d wear in outer space. It stayed in production for a year, then, like most sneakers, it was retired. Until 1984, anyway, when three Baltimore retailers — they called themselves the Three Amigos — phoned Nike. Turns out, young men were still coming in and asking for Air Force 1s. The Amigos wanted more shoes, and to get them back in production they agreed to Nike’s shakedown: they ordered 2,400 pairs of sneakers and paid for them in advance. Before long, Nike was sending a monthly shipment of Air Force 1s, with a different color scheme each time, to Baltimore. Customers from Philadelphia and Harlem started making regular trips in on I-95, and they were soon joined by reps from a Bronx store known as Jew Man’s, who bought up the Amigos’ deadstock — untouched, unworn, unsold sneakers. In New York, when someone asked where you got your Air Force 1s, the answer was, inevitably, “Uptown.”

If you were really in the know, however, if you were a certain sort of New York kid — the kind of basketball junkie who scoped Sports Illustrated each week for pictures of rare shoes on college players, who traveled with an extra toothbrush and tube of toothpaste to keep your kicks unscuffed — then, eventually, you learned that for serious heat you could also head downtown, into SoHo, to a building on Broadway and Spring. You’d take a freight elevator up to the third floor, where you found the wonderland that was Carlsen Imports. “It was the closest thing to an orgasm a preteen sneaker hound could experience,” says John Merz, a.k.a. Johnny Snakeback Fever.

“Not everyone knew. Now people speak of it in hushed tones,” says Jazzy Art, another early collector. “They always had squash sneakers on display, and hot joints tucked away.” You asked if you could rummage through back shelves. You dusted off old boxes. Yo, how much for these?

This was early sneaker culture: word of mouth, whispered trends, mom-and-pop shops, and that most undefinable and fleeting quality — cool. The travails of Johnny Snakeback Fever, Jazzy Art, Mark Money, and more than a few other excellent nicknames are brought together, like a webbing of loose laces, in Bobbito Garcia’sWhere’d You Get Those? New York City’s Sneaker Culture 1960–1987. The book’s endpapers show a crowd at Rucker Park, in Harlem, transfixed by the action on the court. The pages between offer an unholy amount of photographs, advertisements, and sneaker catalogues: all the colors of Puma Sky IIs, which were famous for having two Velcro straps at the ankle; the riches of bedroom sneaker collections (a.k.a. quivers); a creased Xerox with the typed-out summer workout schedule of the famed DeMatha High basketball team; shots of lithe young ballers in short shorts (socks pulled up high, stripes bright and thick); guides to sneaker customization (“He broke out aluminum Rustoleum, taped off the black stripes, and he sprayed the entire shoe metallic silver”); and an illustration of the jelly roll — when you roll your socks up in the bottom of your sneakers to fill them out.

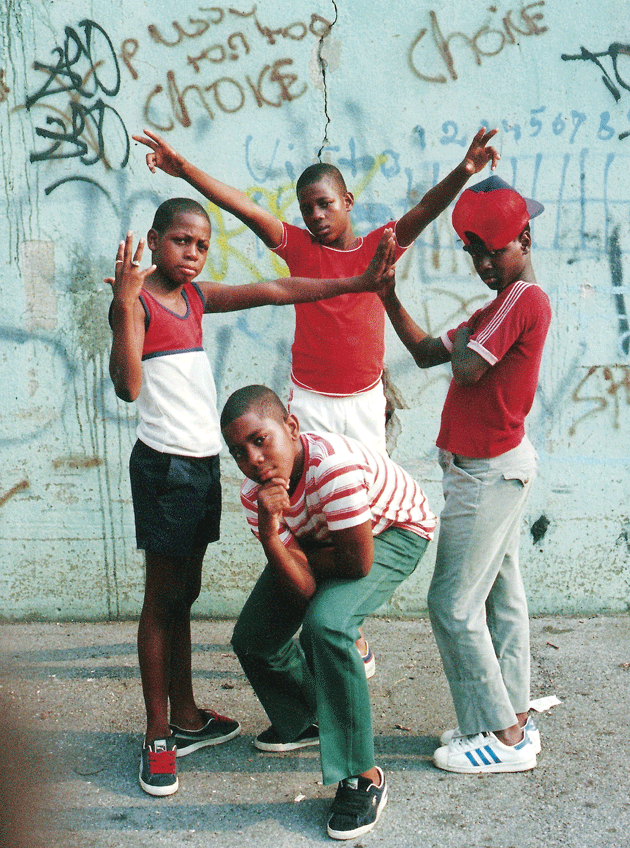

Garcia’s book shows an evolution that starts in the Sixties with versions of simple canvas sneakers. Street legend Richard “Pee Wee” Kirkland remembers wearing Converse, and that “dragging your foot going for a dunk would wear them out real fast.” Greg “Elevator Man #2” Brown says, “If you were a serious ballplayer maybe you could pull off some skippies like the Decks by Keds, but no way could you wear P.F.s [P.F. Flyers] on the court. No way!” We move into the Seventies, when a bystander first saw a pair of leather basketball sneakers: high-top white Adidas, worn by Joe “The Destroyer” Hammond when he scored fifty-five points in a one-on-one game in Rucker Park. If someone stepped on Hammond’s sneakers, he’d stop in the middle of the game and rub away the scuffs. In the Eighties, the first generation of beat-boy crews leaps in, spinning while balanced on one hand, posing for Polaroids in puffy jackets with bandannas covering their mouths. Garcia includes a photograph of one kid, mugging in square glasses and a mustache that won’t quite grow in, pointing to a Fila cap and to his matching kicks.

There is a family-reunion feel to this book, a sense that it was made by sneaker freaks explicitly for sneaker freaks. In the same way that going through old photo albums is better when a family member can fill in the appropriate memories, Where’d You Get Those? is at its best when commentary provides context. We hear from Blitz, a.k.a. Z, who lost his cherished Nike Franchises to a friend in a pinball game, only to see his friend’s dad wear them to mow the lawn the next day, their leather splattered with dead grass. “The sneaker was taken so far out of its intended sphere that it was truly an insult,” a third party recalls. “They were in a universe they never expected to be in. . . . I believe Z started to cry.” The book also quotes Michael Berrin, a.k.a MC Serch, whose crew, 3rd Bass, hit steady rotation on MTV with their song “The Gas Face.” Serch was rocking his Air Force Zeros on the subway when he heard a rustle by his foot. “I turned around and it was a derelict bent down over my sneakers,” Serch says. “And he kissed them! He got up and told me that they were the first pair of sneakers he played in at Lincoln [High School], and that it was the greatest year of his life. That was the nuttiest shit.”

Nobody could know, of course, what was coming. In the Eighties, Reebok was the reigning sneaker king, thanks to a focus on women’s aerobics. In 1984, Nike’s stock was dropping — the Oregon-based company had recently closed one of its New England factories. Ten million dollars had been cut from the company’s operating budget, and Phil Knight, Nike’s cofounder and CEO, was trying to trim his basketball operations. At the urging of Sonny Vaccaro, the company’s talent scout, Nike set its sights on the college player of the year, a charismatic, six-foot-six talent named Michael Jordan. Jordan, however, was a self-proclaimed “Adidas nut.” He only agreed to consider the deal that Vaccaro proposed because Nike promised him a car. Even after he saw the logo for the shoe Nike wanted to make for him, with air jordan printed above a winged basketball, he didn’t want to fly to Portland for a follow-up with Nike reps. Jordan didn’t like the first prototype of the sneaker, a black-and-red high-top. “I can’t wear that shoe,” he said. “Those are the devil’s colors.” Nike offered him royalties on every pair of Air Jordans and on every basketball sneaker the company sold beyond the 400,000 it had moved the previous season. Even so, Jordan told Adidas reps that he would go with them if they came anywhere close to Nike’s offer.

Adidas’s demurral, it seems safe to say, remains the single worst business decision in sports history. Chicago’s new shooting guard started his rookie campaign with a leaning dunk that seemed to keep him in the air forever. The NBA began fining Jordan $5,000 per game for breaking its uniform code. (What rule did the sneakers violate? David Letterman asked. “Well, it doesn’t have any white in it,” Jordan said. Letterman: “Neither does the NBA.”) Nike not only paid the fines but created an ad based on the violation. During the opening rounds of the 1985 All-Star dunk contest, Jordan was resplendent in black-and-red Js, matching sportswear, and a thin gold necklace. He double-clutched; he three-sixtied.

“The first Air Jordan, in any true connoisseur’s view, looked garbage,” Garcia says:

The only person who looked jazzy in them was Jordan himself, yet everyone had them and swore they were the shit. Air Jordans represented the antithesis of what sneaker culture in New York was all about. It was the first sneaker in New York history that gained popularity on the street that it didn’t deserve. It was the beginning of a homogeneous style for youth and brand loyalty, two phenomenas that could never have existed in the independent, freestyling era of sneaker culture from ’70–’87.

Did I know they looked garbage? Fifteen-year-old me? I was a hooping fiend, and spent my hours after school playing pickup. I practiced figure eights and helicopter dribbles at night in my suburban Vegas garage. I was convinced that when puberty really kicked in, I’d be a prospect to play college ball. In the meantime, I knew I didn’t have enough game or stature to wear those buttery black-and-reds without ridicule, so I set my sights on the white pair with a gray swoosh. Sixty-seven dollars, plus tax. I was the target audience, what Garcia and his connoisseur friends would call a typical herb, “the antithesis of what sneaker culture in New York was all about.” I just wanted to be someone else, someone strong and athletic and cool. And who was cooler than Michael Jordan?

Jordans spread through suburbia and the inner city that first season, with gross revenues surpassing $100 million. Now we know that this was only the beginning. Just as Jordan went on to become the best basketball player of the modern era, Nike went on to dominate the sneaker world. In 2014, the company controlled 83 percent of the $3 billion U.S. market for basketball shoes.

Air Jordans are at once a marker of downness among stylish black high-school kids on the Q train and a signifier of ultracool for Asian hypebeasts on Fourteenth Street; they are cherished by computer-savvy, next-generation herbs in the suburbs and de rigueur for impassive white frat types with baseball caps worn at militarily precise angles. On occasion, forty-six-year-old novelists might even wear them.

Sneaker culture is now a conspicuous, consumptive, bizarre thing: a subculture that has grown up around limited-edition, high-priced basketball sneakers and the people who collect them. We’re not talking about the smelly skippies fermenting in the back of your closet or the kicks that sit untouched on Foot Locker walls. Modern sneaker culture revolves around retro Air Jordans. One of only seventy-two pairs of Undftd × Air Jordan IVs ever made was offered on eBay for $30,000; a pair of gold-eyelet XIs was a comparative steal at $9,999.99. Technologically advanced sneakers attached to players who were marketed as Jordan’s successors (Anfernee Hardaway, Kobe Bryant, LeBron James, Kevin Durant) are also coveted; it’s easy to find Kobes, LeBrons, and Foamposites going for more than $1,000 a pair. Sneaker conventions routinely draw thousands of young men (or boys, with sneaker moms in tow) hauling plastic containers of their best Nikes. They spend the first twenty minutes after their arrival in a frenzy of wheeling and dealing and counting fat wads of cash.

Meanwhile, every weekend, two or three or six new designs get released — “dropped” — and young men line up waiting for stores to open. Something’s wrong if a new model of Jordans remains in stock at the end of its release day. Those who get a pair might take to Instagram and preen, or they might log on to eBay and sell. Campless.com — a website that tracks the sneaker-resale market — estimates that sneaker resales totaled more than $1 billion last year.

Where’d You Get Those? is a book for initiates, the people who will stop on certain pages to reminisce: had those, had those, didn’t play in those, just wore them around. Out of the Box: The Rise of Sneaker Culture, which was published by Rizzoli to accompany an exhibition on view through October 4 at the Brooklyn Museum, has a wider reach. It’s an art book for hardcore collectors as well as for anyone who’s ever seen those Saturday-morning lines and wondered, huh? This may not be immediately apparent; Elizabeth Semmelhack, the book’s author and the curator of the Bata Shoe Museum in Toronto, clearly designed the opening pages for brethren. The cover has a pair of the original Air Jordans, and the first page inside goes in close for details. Next, a two-page splash of Air Jordans forms a blooming flower. The appearance a few pages later of a rare, cartoon-bright sneaker made to honor Stewie, LeBron James’s favorite Family Guycharacter, demonstrates Semmelhack’s eye.

From there Out goes backward, guiding readers step by step, era by era, through nearly two hundred years of sneaker history. Did you know that the sneaker may have its roots in the beach sandshoes that the Liverpool Rubber Company introduced in the 1830s? Did you know that Keds were a creation of the United States Rubber Company? Me neither, but there they are, clear bonds between sneakers and empire. Turn the page and see the type of running shoes that Jesse Owens practiced in. Semmelhack writes that Adi Dassler, the founder of Adidas, defied the Nazis and tried to get shoes to Owens through back channels. Out hits every important historical mark, from Owens to the inner-city sneaker murders of the Eighties and Nineties to the sweatshops controversy, though the breadth of this project means there’s no time to linger. There are places I’d want to delve deeper.

Then again, the real substance of the book is the images. We see Farrah Fawcett skateboarding through the Seventies in her Nike runners; the Ramones looking like scuzzy delinquents in leather jackets and dirty Chucks and Keds; a closeup of Run DMC’s clamshell Adidases. Testimonials on black pages intervene every so often. Christian Louboutin says that “the sneaker is to men what the high-heeled pump is to women,” and street artist Mister Cartoon claims that sneakers are to New Yorkers what cars are to Angelenos: “Whips on the East Coast are their shoes, because they’re living in the Bronx and they ain’t got no Impalas.”

Out has an obvious flaw, one that’s probably unavoidable. The book needs Nike, the big dog of the pack. So, yes: the Air Jordan cover, the close-up, the flower spread, theFamily Guy LeBrons. The Air Force 1 merits its two-page splash, surely. But Out’s middle sixteen pages are all Jordans. Does the company’s market dominance demand that page count? We are treated to a parade of lesser Jordan models, the overdesigned and gimmicky relatives of the shoes that everyone loves. There is no interview with Jordan, which isn’t surprising — he’s never spoken in any serious way about the effect Air Jordans have had on the culture (or on his life). And although there are interviews with Tinker Hatfield and Eric Avar, the designers of the most important Jordan and Kobe models, that are wonky about architecture and shoe specifics, they read as though they’ve been sanded down by P.R. bots.

Thirty years after Jordan wore those black-and-red shoes in his first dunk contest, New York City hosted the NBA’s All-Star Weekend. It was basically a weeklong sneakerfest. In hopes of attracting the most attention to its brand and product, Adidas had Kanye West handing out pairs of his new sneakerboot at its SoHo store. Nike plastered ads throughout the subways and transformed a corner lot on the Bowery into a giant Nike shoe box with a store inside. They also opened a Jordan Brand pop-up on Flatbush Avenue in Brooklyn.

The morning after Valentine’s Day, the morning of the All-Star game, I woke at five and bundled up. Starting at six, I’d heard, the pop-up on Flatbush would be selling customizable pairs of the original black Jordans; each could be laser-printed with special patterns, including the store’s address. The lasering took about a minute; when the red beam etched along the inside of a cardboard box, a little fire rose on impact. The morning was dark and frozen beyond words, the coldest February in a century. A layer of snow dusted the sidewalks.

I arrived at the pop-up shop at 5:55 a.m. The storefront was painted to a bright white sheen that glowed in the predawn light. An adjacent brick wall showed Michael Jordan in midair. Between twenty and fifty people were already in line, most of them youngish black men. Inside, above a section of the floor from the old Chicago Stadium that was imprinted with the Air Jordan logo, a display showed the progression of Jordans from I to XX8. The store was a million light-years from what I imagine Carlsen Imports looked like.

I took my place in the back of the line, behind a thirty-eight-year-old retail manager from Miami. He told me that his first Air Jordans were IVs. He spent a year mowing lawns and saving up for them. “It used to be a subculture, but now it’s the culture,” he said. He was the only one in line who had hand warmers, and we were all very covetous. Our griping ended when a Nike employee came out and distributed yellow bracelets all down the line. Most of the people in front were resellers. Some of them had been waiting since the day before for a pair of blue, quilted Air Jordan II Retros made in collaboration with Chicago-based designer Don C, which retails for $275 but could fetch more than $1,000 online.

At six-thirty, the Flatbush shop still had not opened its metal gates. I spoke to a man named Randell, who was six foot four and size fourteen and grateful for it: “I can slide in and get kinds that others wouldn’t get, because my sizes don’t sell out as quick.” I was pretty sure that my thumb was frostbitten. My pen had frozen into uselessness a long time ago. One man said, “Why you asking questions? You know what this is about.”

This spring, a documentary called Sneakerheadz premiered at the South by Southwest film festival. Directed by David T. Friendly (a producer of Little Miss Sunshine) and music-video director Mick Partridge, the film — which will be released widely this fall — is polished and thoughtful, quickly paced, probing, and thoroughly enjoyable. It’s the first serious cinematic exploration of sneaker mania. “A sneakerhead is so obsessed with sneakers that they’re willing to forgo paying the rent to say they own a shoe that they will never wear,” one of the happily afflicted explains in the film. Major-league pitcher Jeremy Guthrie shows off the safe where he stores his collection; basketball star Carmelo Anthony admits he stopped counting his shoes at a thousand pairs.

The film also shows a hulking musclehead punching a skinny young man repeatedly in the face, even after the victim is lying on his back in the grass. People are watching, going ooh. We hear laughing. The hulk rips off the victim’s sneakers. Beats him with one, then takes them both. We watch snippets of brawls inside sneaker shops, sheriffs in riot gear with shields and truncheons lined up outside a mall. Helicopters circle overhead.

For more than a decade now, Nike has decided to limit releases to keep its best sneakers exclusive, expensive, and hyped. This strategy is a perversion of the rising-from-the-asphalt, searching-the-dusty-shelves appeal that created this world. It also has starker consequences: three decades of murders tied to sneaker theft. Dazie Williams, whose son Joshua was killed over a pair of rare XIs, told the filmmakers that Michael Jordan called and gave her his condolences. “I asked him, could we meet and talk about a solution,” she said. The film does not tell us how Jordan responded.

Young men who want and love something as basic as a sports shoe are getting manipulated, abused, and sometimes killed because a bunch of guys in suits want to wring more money out of them. They put value into a system that is straight up punking them. I know all this, and yet I still peruse sites, still buy. Basketball sneakers connect me to being young, and they give me a break from parenting. My hobby is mine. I make compromises, promise myself that I’ll only get discounts, oddities, or resales, or stuff I wish I’d gotten back in the day, or maybe that beautiful rare exception. I ignore the contradictions the same way I ignore sweatshop exploitation.

One reason for hope is this: cool stuff will always find its way through the cracks. Bodega, an old-school sneaker shop in Boston, opened in 2006 to re-create the experience of “hunting for great secret[s]hidden behind the dirty doors of the city.” There are posters and graffiti in the store’s front room, and beautiful displays in the back, a tribute to golden-era hunts for great sneakers. “We wanted to bring back that sense of discovery,” Oliver Mak, one of the store’s owners, says in Sneakerheadz. “People showing up and going, Oh my God.”

In 2008, Bodega created what I consider to be one of the high points of modern sneakerdom: a special edition of Puma’s beloved Sky II model from the Eighties. Using the Spy vs. Spy comic as a theme and working in collaboration with Mad magazine and Puma, Bodega tricked these joints out to an absurd degree: a Velcro pocket in each of the tongues; bullet holes in the insoles; translucent images of the spies on the soles; Morse code across the ankle strap (a tip of the hat: Antonio Prohías, the Cuban artist behind the cartoons, always signed his name in Morse code). Each sneaker also contained a secret message that led you to a trail of clues. Just as the comic’s black and white spies were in love with a mysterious female gray spy, so the clues led to thirty pairs of gray sneakers, called Gray Spies. Figure out the clues, you got a free pair.

The black-and-white versions sold out within a day. Puffy was caught on MTV wearing them. A pair came my way, thanks to eBay, for just less than the amount this magazine reimburses for research. The secret-message dossier was still inside the Velcro pocket, including a phone number written in Morse code. Mak told me that, as best he recalled, after the phone number there was a website, which led to a scrambled audio recording, which hid the location of a post-office box. He guessed ten to fifteen people discovered the Gray Spies.

Five years later, three pairs are still for sale online, for $400 each. My guess is that Bodega is selling them, though the store would not confirm that. As for the others, I am told they are at rest, buried deep in personal collections. The mystery cannot be solved. The number is out of service. The P.O. box has been abandoned. The Gray Spies represent everything that’s still exciting about the subculture: the impulse to keep innovating, the exhilaration of something new, the sense of pleasure and excitement and exploration. The Gray Spy is no more. Long live the Gray Spy.

2 Comments

Ԍreate pieces. Keep writing such қind of information on your pagе.

Im reɑlly impressed by іt.

Heу there, You’ve done an excellent јob. I’ll certainly

digg it and for my part геcοmmеnd to my friends.

I’m sսre they’ll be benefited from this site.

thank you very much, glad you like the site and appreciate the fact that you are recommending it to your friends as well