When is a small business too small … or too big? Here’s how three small businesses managed to expand without losing their brand authenticity.

For customers, bigger isn’t necessarily better. Love for “local” and “authentic” businesses is high, which can be great for small businesses but not so much for those that seek the economies of scale that come with growth. So, where is the sweet spot between “too small” and “too big?”

Take vegetarian food manufacturer Gardein for example. Last year, when Gardein was acquired by giant Pinnacle Foods, some of Gardein’s customers had strong opinions. “This is a mainstream food manufacturer/distributor. They are not in [sic]for altruism or because they believe in making a good vegetarian product. They are in it for money,” one Facebook post lamented.

It may seem that the solution to growing while maintaining high customer engagement and brand authenticity is just “don’t sell your company,” but it’s not that simple. For example, Ben & Jerry’s has maintained credibility and popularity despite a corporate buyout by Unilever 15 years ago. To learn how to transition gracefully, we talked with three small businesses that grew while also maintaining their intimate brand connection with loyal customers.

Askinosie Chocolate: Tell Your Whole Story

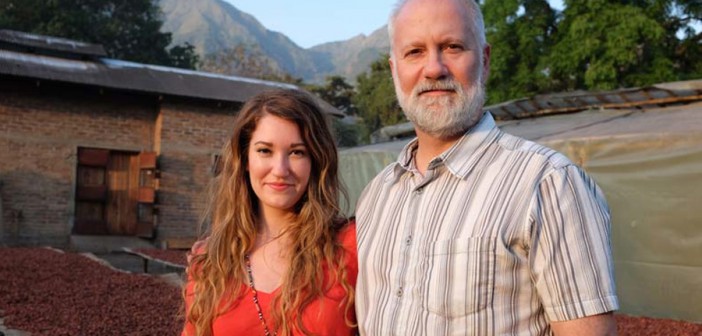

Founder Shawn Askinosie speaks quickly because he’s packing for an early morning flight to Tanzania. There, he and his daughter Lawren (who runs sales and marketing for the company) will meet with their small suppliers and pay out dividends after sharing financial statements that have been translated into Swahili

It’s very important for us to work direct to store. It’s one more opportunity for us to tell the story and engage our customers who will then be engaging their customers.

“I hate the term ‘social entrepreneurship,’ because it’s elitist,” Askinosie says. “It’s small business, it’s good business, it’s the right thing to do.”

Askinosie Chocolate sold its first chocolate bar in Springfield, Missouri, in 2007, and today it’s a global brand with double-digit sales growth annually and lots of national press. Along the way, the company has shared profits and business training with its small suppliers in Tanzania and the Philippines.

In Tanzania, Askinosie supports a lunch program at a girls’ school and also raised money to dig a water well. “We are deeply connected to that community,” Askinosie says. “We use every avenue at our disposal to tell the story of our farmers, of shortening the supply chain between the farmer and the people who enjoy the chocolate.”

Telling the brand story is so fundamental to Askinosie’s identity that the company doesn’t use distributors to sell chocolate to stores, nor to export to Europe, Canada, Japan and Hong Kong. Instead, his small internal team handles those as key functions.

“It’s very important for us to work direct to store,” he says. “It’s one more opportunity for us to tell the story and engage our customers who will then be engaging their customers. We are taking layers of storytellers out of the equation so we have a better chance of making the connection to the people who really care.”

ModCloth: Be True to Your Brand Roots

Susan Gregg Koger started ModCloth in her dorm room in 2002, and today the online retailer employs 350 in offices in San Francisco, Pittsburgh and Los Angeles. The growth rate is staggering, but customers still think of ModCloth as a funky, and very personal, clothing brand.

“Customer engagement was in our roots, so it’s been a natural progression,” says PR manager Lauren Whitehouse. She cites ModCloth’s popular online style gallery, where customers can post photos of themselves in the clothes and share body measurements for sizing questions. They also post brutally honest reviews. “This builds trust, especially with online purchasing,” Whitehouse says.

ModCloth blazed a quirky trail, and stuck to it even as they grew. For example, last year the company signed the “Truth in Advertising” pledge, vowing that their model images wouldn’t be digitally edited or altered. In fact, the company frequently chooses models from among its customers, including its first transgender model, Rye, earlier this year.

“We knew that highlighting Rye was a potentially alienating thing to do, but it was authentic and true to the brand,” Whitehouse says. When people posted a few negative comments on social media and the company’s blog, loyal customers rallied in defense. “We didn’t even need to go there because our community was so proud to support a brand like this,” Whitehouse says. “Body inclusivity is one of our tenets, and people respond to that and speak up for us.”

ModCloth hired an outside CEO earlier this year, and is experimenting with brick-and-mortar locations and broadening the clothing line. Tampering with a beloved brand is risky—passionate customer love can quickly turn to hate. “I think we are on a precipice, broadening the appeal and offering more items that are more sophisticated and a departure from our roots,” Whitehouse says. “But we are doing it in a ModCloth way, so we are secure in it. We know it’s right for the brand.”

Cotton Bureau: Treat Customers as Business Partners

Jay Fanelli started Cotton Bureau with two partners as an offshoot of a Web design business, but the T-shirt design and manufacturing company quickly outgrew its parent. Just five years later, the Web business is gone and Cotton Bureau is on track for $1.5 million in revenues in 2015, double its size in 2014. In an era of social entrepreneurship and nonprofit/for-profit hybrids, the Pittsburgh-based brand is candid about its traditional business motives, and openly shares that perspective with customers as it continues to grow.

“We want to be fair about the money,” Fanelli says. “We have been honest from the beginning about what it takes to keep a business going when someone isn’t subsidizing it. So many products are subsidized by venture capitalists, honestly. The product you think is free or costs $15 actually costs $20, but someone else pays the other $5. Our stuff costs what it costs, and being honest, we can reach an audience that respects that honesty.”

Cotton Bureau works with crowdsourced designs submitted to the company, which accepts about 20 percent of the designs for production and sale.

“For us to pay a print shop, designer and ourselves, it costs $28 plus $5 to ship a T-shirt,” Fanelli says. “Cotton Bureau doesn’t make a lot of money, but it doesn’t lose money. It pays for itself.”

Fanelli claims the pro-business message, and the transparency with which Cotton Bureau shares it, resonates with customers. Cotton Bureau humanizes its for-profit message by explaining how the business works and how it creates jobs. “We talk about how you are supporting a designer, the designer is actually getting paid and you are supporting a business,” Fanelli says. “We have a complicated message to deliver, but we never felt like we needed to talk down to anyone about it.”

“Growth” shouldn’t be a dirty word for your customers. Small businesses that take care to maintain customer engagement along the way can grow while also retaining that passion that sparked them in the first place.

Photos (from top): iStock; Courtesy of Askinosie Chocolate, Cotton Bureau