Do you want to persuade more people to take action? Wondering how the latest behavioral science can help your marketing?

To explore how to be more persuasive in your marketing, I interview Jonah Berger on the Social Media Marketing Podcast.

Jonah is a marketing professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School and author of the books, Contagious and Invisible Influence. He’s also a keynote speaker and marketing consultant. His newest book is The Catalyst: How to Change Anyone’s Mind.

Jonah shares the five key barriers marketers face when trying to persuade someone to do business with them and explains how to use these barriers for customer-centric marketing that produces results.

Behind Persuasive Marketing

In 2013, Jonah wrote Contagious, which explored ‘word of mouth’ and why certain products, ideas, and behaviors catch on. While researching the book, he spoke with and consulted for everyone from big Fortune 500 companies to small startups, and from industries he knew well to industries he knew almost nothing about.

His research showed him how a broad spectrum of marketers and leaders work today. Everybody Jonah spoke to had something they wanted to change—whether it was someone in sales or marketing who wanted to change a customer’s mind, an employee who wanted to change the boss’s or a colleague’s mind, or a leader who wanted to change an entire organization.

Jonah dug into existing research in the influence and change space. There seemed to be a block between what people were doing and what was actually working. He noticed that most people were doing some version of pushing—giving people more information, adding more facts, following up over email, making another presentation—to show the other person why they were right and why the other person needed to come around to the right side.

Our notions of influence come from physics. For instance, if we want to move a chair, we tend to push it, which works. For physical objects, pushing is a great idea. Unfortunately, bosses, clients, and customers aren’t inanimate objects. When we push them, they don’t just go along—they push back.

The Catalyst

The simple question behind The Catalyst is: If pushing doesn’t work, could there be a different, better way?

This concept actually comes from chemistry, a completely different scientific domain. Creating change in chemistry is often difficult. If you think about plant matter turning into diamonds or carbon turning into something else, it takes thousands of years for this change to occur. For this reason, chemists often add a substance that makes change happen faster and easier. These substances are called catalysts.

What’s most interesting about catalysts is how they help change happen. They don’t increase the temperature. They don’t increase the pressure. They don’t push harder. What they do is lower the barriers to change. They make the same amount of change happen—not by pushing but by reducing barriers, making it easier for change to occur. Scientists working with catalysts have won multiple Nobel prizes in chemistry. We use catalysts in everything today, from our contact lenses to how we clean our cars.

Catalysts are also a really important factor in the social world. It’s an approach of stepping back and not adding more forces to push people in one direction or saying, “What could I do to get someone to change?” Instead, this approach asks, “Well, why haven’t they changed already? What’s preventing them? What things are stopping them from changing? What obstacles are in the way? And how can I mitigate them?”

Think about a car parked on a hill. When we want our car to go, we turn the key in the ignition and we put our foot on the gas. If the car doesn’t go, we just think we need more gas. But sometimes, we don’t need more gas. Sometimes we just need to release the parking brake. Similarly, if someone doesn’t change, we just think we need to push more. But sometimes we don’t need to push more.

That’s what this approach is all about. How can we find those barriers and obstacles—those parking brakes—and how can we release them?

Robert Cialdini, author of Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion, is one of the most famous researchers on how we think about persuasion and influence. He even has a more recent book called Pre-Suasion, which is about what happens before persuasion. Jonah’s premise is similar in some ways to persuasion, but in other ways, it’s very different.

It’s the same in that it’s about trying to get people to do something. It’s different in that persuasion is often more about adding something than removing something. Those tactics are useful sometimes but not always.

Hear Michael Stelzner interview Robert Cialdini about Pre-Suasion.

Customer-Focused Marketing: Pull vs. Push

The big trend in marketing today is to be “customer-centric,” to think more about the customer and what they need. At Wharton, Jonah teaches the core introductory marketing class to incoming MBAs. He talks a lot about being customer-focused instead of product-focused, and starting with the customer.

But in sales or marketing, we often end up trying to push what we have rather than being customer-focused. Rather than trying to make what we can sell, we often try to sell what we can make. We think about what we already have and how to sell that.

Persuasion tends to come from a place of, “This is what we’re doing, and you should do it,” rather than, “Why aren’t you doing what I want you to do, and how can we get you to do it? How can I show you that what I want you to do is actually very much in line with what you already want? How can I help you get where you want to go by following what I’m interested in?” It’s an important, but very different, way to think about things.

To really make the metaphor of the customer journey work, we have to understand where someone is in their journey. Someone might not be aware that a product exists. Some might be aware that it exists but they might think it won’t work for them. Someone might think it could work for them but they don’t understand how it works. Someone might think it works but they think it’s too expensive. Someone else might think it’s not too expensive but they’re worried it’s not going to integrate with what they’re already doing.

There are various stages in that customer journey and if we don’t know where someone is, it’s going to be really hard to get them to change.

When you go into the doctor’s office, the doctor doesn’t just say, “Here’s a splint for your finger.” The doctor first asks about the problem and then figures out what the solution is. As marketers and salespeople, we tend to think a lot about ourselves and our product or service. We know a lot about our product or service. We know why we think it’s great. We have a series of talking points and we think if we just mention them enough, someone will come around.

We don’t think as much about what their needs are, why they haven’t purchased something or done something already, and how we can mitigate those obstacles. If we don’t understand what those barriers are, it’s going to be really hard to get that person over them and toward change.

The REDUCE Framework

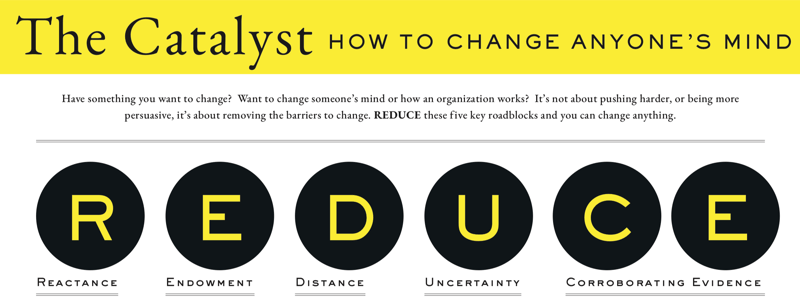

Jonah’s research showed five key barriers that we often encounter, whether we’re trying to change a customer’s actions, the boss’s mind, or even something in our personal lives. Those five barriers are reactance, endowment, distance, uncertainty, and corroborating evidence.

Reactance refers to the fact that when we push people, they tend to push back. People want a sense of freedom or control. When we usurp that, they push back.

Endowment is the idea that people are attached to what they already do or have. They tend to be emotionally attached to things they’re doing already, and they’re unwilling to let them go. As marketers, we’re trying to get someone to buy into something new. If they already have something else they’ve been buying, then they already have something they’re attached to. So we’re not just trying to get them to do something—we’re also trying to get them to let go of something else, which is actually more challenging.

Distance is about how far away an ask or information is from where people are already. People have an existing perspective. If what we’re talking about is too far away from where they are at the moment, they tend to discount or ignore what we’re saying. If they’re a Democrat and we’re a Republican, or vice versa, even if we’re just sharing information, they don’t even listen because it’s so far away from their existing perspective that they don’t want to consider it.

Uncertainty is less about the past and more about the future. New things always involve some sense of uncertainty. A new product or service might be better but people don’t know if it’s better so that uncertainty often prevents action.

Corroborating Evidence is the simple idea that some things require more proof. For small decisions and things that people don’t have a strong attachment to, only a little bit of proof is needed to make a decision. But for bigger decisions, things that are more expensive or more controversial, there’s more uncertainty and people need more proof or more evidence to help them make those decisions. It’s about how we involve others in that process so people hear from multiple angles to change their minds.

If you put those five together, they create the acronym REDUCE, which is exactly what catalysts do. Good catalysts don’t push harder or try to pressure people; they reduce the barriers to change. They figure out what obstacles are preventing change from happening and how to mitigate them.

The Catalyst devotes a chapter to each of these five key barriers. It talks a little bit about the science of why these barriers occur and then provides case studies and examples of companies, organizations, and individuals that have mitigated these barriers with a variety of strategies.

Reactance Explained

When we’re trying to change someone’s mind—we’re trying to get them to do something, to buy a product, to use a service, or to change the thing that they’re doing—we pitch them in some way, shape, or form. But people don’t like being pitched. They don’t like being persuaded. They like to feel that they’re in control of their own lives and can make their own choices and that they’re driving their own destiny.

People like being in the driver’s seat and having more choices. Whenever we ask someone to do something, we’re impinging on that ability to choose. Rather than feeling like they’re making their own choice, now they’re worried that we’re influencing their choice. Because of that, they lose interest in making that choice, even if it was something they might have wanted to do already.

Think about buying a car. Maybe you were already interested in buying an electric vehicle. But if you feel like the reason you’re interested is that someone’s trying to sell you on one, then you worry that maybe the decision isn’t driven by you but rather by the salesperson. You’re going to react against that feeling, push back, and be less likely to buy the electric vehicle. In a sense, people have an anti-persuasion radar.

Think about a missile defense system that shoots down incoming projectiles. The same thing happens when someone tries to persuade. Whether the person is walking into a car dealership, receiving a sales call or email, or someone is pitching them something in a meeting; whenever that happens, the radar goes off. It’s a red alert and they use a series of countermeasures to shoot down those incoming persuasive attempts.

Even worse for marketers is counter-arguing. Someone might listen to your phone call and although they don’t hang up, they’re not just sitting there listening and thinking about all the reasons that you’re right. They’re thinking about all of the reasons that you’re wrong.

If they hear an ad that says, “The Ford F-150 has best-in-class towing”, they’re not just thinking, “Okay, I bet that’s right. Ford F-150 has best-in-class towing.” They’re thinking, “Well, of course Ford would say that. Chevy wouldn’t say that the Ford F-150 has the best-in-class towing, but Ford would say that. ‘Best in class,’ what does that even mean? Does that include all pickup trucks or only one pickup truck? Are they ignoring the other features like gas mileage, or price, or things that they’re worse on, and only focusing on the attributes that they’re good at?”

It’s almost like a high school debate. Rather than just listening, that consumer is mentally listing reasons why everything you’re suggesting is wrong. Obviously, that makes it really hard to get them to change because rather than just going along, they’re making your message crumble to the ground. Not only are they not listening, they’re thinking about why it’s wrong.

Neutralizing the Reactance

One way to deal with reactance is to essentially provide a menu.

Usually, when we pitch a product or service, we’re asking people to do something specific. Buy this software, use this new consumer packaged good, or check out this new type of service. People then spend that pitch counter-arguing, thinking about all of the reasons that it’s wrong.

It’s the same in our personal lives. If your spouse or a friend asks you what you want to do this weekend, you might suggest seeing a movie. They often don’t just say yes. They say, “Ah, but it’s supposed to be so nice this weekend. Why don’t we do something else?” Or “Oh yeah, but this other thing would be more fun.” They think about all the reasons that your suggestion is wrong.

Instead of suggesting one thing—and this is a subtle shift but an important one—give people multiple options. Instead of one thing, give them two. Instead of “Let’s go see a movie,” try “We could go see a movie or we could go out for Chinese food.” Instead of “Hey, buy this product,” try “You might want to check out this one or this other one.”

This shifts the mindset of the person who’s listening and puts them in a different role. Rather than thinking about what’s wrong with that one thing, they’re thinking about which of those two things they like better. They might not love either of them but they’re focused on which one they like better because rather than thinking about all of the things that are wrong, they’re focused on the things that are right. It’s not about giving people 60 options, it’s about giving them just a few additional choices.

Consultants often do this when they present to clients. They say, “I’ll give them three options about their course of action. If I give them one, they say it’s too expensive or it won’t work. I give them two or three, they’ll think about which one they like best.”

When you walk into a restaurant, they don’t give you any option in the world that you want. If you go to a Chinese restaurant, you can’t have Italian or Japanese food—it’s just a set of options within the realm of Chinese food. But they don’t give you one option. They give you multiple options.

It works with kids, too. If you tell your kids to put on their pants, they say no. If you tell your kids to put on their shirt, they say no. But if instead, you say, “Which do you want to put on first, your pants or your shirt?”, they’re much more likely to do what you want because they’ve had volitional autonomy in that process. They’re much more bought-in so they’re going to buy into the outcome as well.

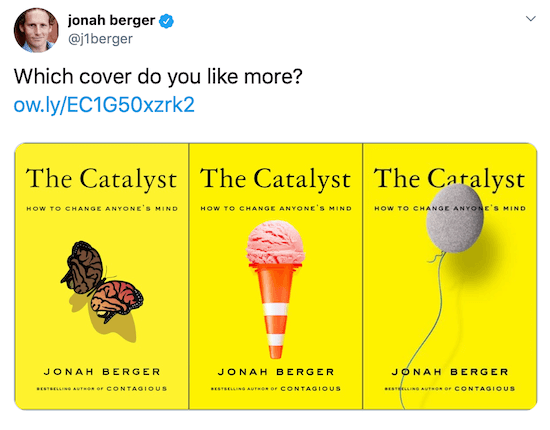

Jonah was picking covers for The Catalyst. The publisher liked one but Jonah wasn’t sure, so he decided to ask some other people. He’s never gotten as much engagement on a social media post as he did when he posted those book covers and asked which one people liked best. Everyone shared an opinion. People love sharing their opinion and by giving them a choice, by providing a menu, that’s what you’re doing. You’re allowing them to share their opinion and they’re going to be much more likely to make a choice at the end of that experience.

Sometimes you’ve only got one product to sell. Try creating a phantom version that isn’t even something you think consumers will want. By offering it, 1) you give them a sense of choice, which should make it more likely they’ll choose one, and 2) if a lot of people choose the one that you didn’t think they’d want, you should probably make that version of what you’re offering after all. Combat reactance by giving people the opportunity to choose and participate.

There can also be versions of just about every product. If you’re selling gym memberships, you only have one product: the gym—but you can offer people a yearly subscription or a monthly subscription. If you’re offering people popcorn, you can sell it in multiple sizes. Whatever you’re selling, there are ways to make multiple versions of it.

The reason why this is so important is that it gives control to the person who’s trying to make the decision. If someone abandons your sales page, you could put out a Facebook retargeting ad that says, “By the way, did you know that there’s more than one option here? Here’s option A, here’s option B.”

Even if you’re a consultant, you could offer group consulting versus one-on-one consulting. For almost anything, you can create a premium version or a discounted version to add an aspect of choice to that process. The more you give choices to people rather than usurping that sense of choice, the more freedom and autonomy they have. This means they’ll have fewer reactance, and they’ll be more likely to move forward.

Another strategy is to ask rather than tell. Rather than telling people why they should do something, ask them a question. Asking questions will again make them feel like they’re participating so they’re more committed to the conclusion, and more likely to go along.

Another way is to highlight a gap. Rather than telling them to do something, point out a gap between what they’re saying they care about and what they’re actually doing, and encourage them to resolve that gap. There are many different ways to combat reactance but the main idea is to allow people to participate in the decision-making process.

Uncertainty Explained

Uncertainty is the reason Jonah started writing The Catalyst in the first place.

The simple way to explain uncertainty is that any time you ask someone to do something new, there are what are called switching costs. Whether it’s money, time, effort, whatever it might be, there are costs to doing something new.

If you buy a new phone, it costs money and also costs time. You have to figure out which one to buy. You have to get your number and your contacts switched over. If you buy a new software package, it costs money and you have to integrate it with your existing systems. It takes effort.

Not only do these costs occur but the costs also tend to occur now and the benefits tend to occur later. So when you ask someone to buy a new phone, it might be better for them, they might enjoy using it more, and it might have more storage space. But until they pay for that new phone and they deal with all of the switching costs, they’re not going to get that benefit. Same thing with a new car, new software, or a new process.

With almost anything we do, the costs often occur now and the benefits often come later. Nobody wants that. Everyone wants the benefits now and the costs later so we’re skiing uphill already.

But it gets even worse because new things always have some element of uncertainty. Whatever they’re doing now, whether they like it or not, they’re certain about it. In the case of internet service providers, Jonah recently talked to someone who called it the “old boyfriend” problem.

You have an existing service provider, and you may not love it, but you know exactly what it is. Whereas with the new thing, you’re uncertain. It could be better but it also could be a lot worse. So that’s often a challenge.

As a marketer, you say your new product or service is better, but how does the consumer know it’s better? Notice that they have to pay the cost to resolve that uncertainty.

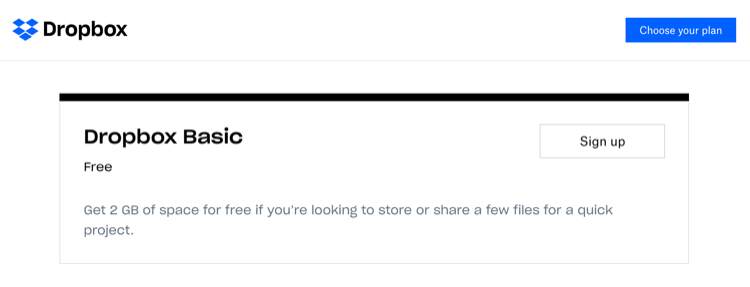

Think for a moment about freemium. Whether it’s Dropbox, Pandora, The New York Times, or Skype, many software- or service-type companies use some version of a freemium. There’s an initial thing that’s free but they encourage you to upgrade to a premium version. In the case of Dropbox, they give you two gigabytes of storage for free, but eventually, if you want more storage, you have to pay to upgrade. What does that do?

Well, sure, the marketer can say Dropbox is great. But you’re not going to trust them and you’re going to react against the message. What freemium does is it says, “Hey, don’t trust us. You don’t have to believe us. Check it out for yourself, for free.” If you like it, and you hit the two-gigabyte limit and need to upgrade to the better version, you’ve already convinced yourself it’s worth the money.

When we think about using freemium, we have to think about what we give away. If we give away too much, people will never upgrade to the premium version. If YouTube said, “Have YouTube TV free for the next 10 years,” you would never get to the point where you needed to upgrade. If The New York Times said, “Here are 50 articles a month for free,” no one would ever pay for the premium version.

At the same time, if we don’t give people enough of an experience, it’s not going to be enough to get them to be willing to pay. If YouTube TV says, “Hey, for the next 2 minutes, you can check out YouTube TV,” that’s not going to be enough of an experience for me to figure out if it’s any good. So it’s really important to think about what we give away and how we make sure it’s not so much that people don’t want to upgrade to the premium version.

A good way to think about it is that at the front end, we lower the barrier to trial. We make it easier for people to experience something. But at the same time, they have to see that there’s something better on the other side—otherwise they stay in the free state forever. In the case of YouTube TV, it’s the 30-day free trial.

Once the 30 days run out, you don’t get to try it anymore. An even better trial might be to give you access to some features of YouTube TV but not all features—make people realize that they want the full-featured version. What a good freemium does is it gives you a sense of what’s being offered but not too much of a sense.

Freemium works for some things but not everything. It works for YouTube TV because it’s online and it’s easy to give away 30 days for free. But how do we do that with something physical or real, or a service? We either lower the upfront cost, or we lower the backend cost. We make it reversible.

Think about a test drive. A test drive isn’t freemium; there’s no free version or premium version. A test drive allows people to experience the offering just like YouTube TV did. It doesn’t make it any cheaper once they buy it but it allows someone to experience the offering before they buy.

Think about renting. Renting equipment lets people experience it before they’ve committed to buying it. A 30-day free trial does the same thing. We can do the same on the back end: Make it reversible with return policies or money-back guarantees. Lawyers say, “We only get paid if you win.” All of these things make people feel more comfortable with taking the plunge because they know that in the worst case, if it doesn’t work, they can turn around and give it back.

Years ago, Jonah was thinking about adopting a dog but he wasn’t sure he was home enough to actually have one. One day, he was at the shelter visiting the dogs and the supervisor said, “You seem like you really love this dog.” Jonah said, “Yes, I do. I’d love to take her but I’m not sure I could give her a home.” So they said, “Oh, we have a 2-week trial policy!” That dog is named Zoe and she has now lived with Jonah for the past 8 years.

But he may never have gotten her without that 2-week trial policy because it made him feel more comfortable that if it didn’t work out, he could bring her back. That’s the exact idea: lowering the barrier at the front end and making it reversible at the back end.

The cost of returns is usually more than paid for by the increase in sales that comes as a result. We tend to think of returns as a cost center and institute strict return policies. But research shows that more lenient return policies are actually better for two reasons. First, yes, people do return but they buy more things. They return more but they also keep more as well, and they share more word of mouth.

Zappos, for instance, wants you to buy 10 pairs of shoes. Sure, you return eight of them but you keep a second pair when you maybe wouldn’t have if it wasn’t for that open return policy because you wouldn’t have bought as many in the first place. You also go back to Zappos the next time you want shoes.

When that works, it’s about understanding that barrier. Why isn’t someone buying something? Because they’re not sure if it’s going to be any good. How can we make it easier for them to feel comfortable testing it out so they see if it’s any good? And if it doesn’t work for them, fine, they bring it back. But more people are going to check it out and more people are going to end up keeping it.

We can also go a little further in informing consumers up front, especially online—the availability of information can help reduce uncertainty. But we need to be careful. There’s a difference between us providing that information and someone getting that experience for themselves.

When the information comes from us as marketers, people are going to be less likely to trust it. Acura can say, “We make amazing cars,” and they can provide lots of details on their products. But I want to be able to sit in that Acura myself to see if I like it and if it’s a good fit for me.

Information can reduce uncertainty. Product reviews can reduce uncertainty. But the more unbiased that information is, the bigger an impact it’s going to have. Getting authentic customer reviews is super-important. Word of mouth is the second-best thing. The absolute best thing is personal experience. You know if it works for you. The next best thing is your friend’s experience. The next, next best thing is the marketer or company saying it’s good.

Key Takeaways From This Episode:

- Find out more about Jonah on his website.

- Read The Catalyst.

- Follow Jonah on LinkedIn and Twitter.

- Get your Virtual Ticket to Social Media Marketing World 2020.

- Watch exclusive content and original videos from Social Media Examiner on YouTube.

- Watch our weekly Social Media Marketing Talk Show on Fridays at 10 AM Pacific on Crowdcast.

–

This article first appeared in www.socialmediaexaminer.com

Seeking to build and grow your brand using the force of consumer insight, strategic foresight, creative disruption and technology prowess? Talk to us at +9714 3867728 or mail: info@groupisd.com or visit www.groupisd.com