At Converse’s Concept Creation Center, shoes go from idea to collection in a matter of months.

I’m in an industrial building with cement floors and exposed steel beams running across the ceiling. On small pedestals are Converse’s iconic Chuck Taylor sneakers, but redesigned in wild ways. One pair is covered in what looks like red spider veins; another has soles covered in confetti.

“These are the Chucks of the future,” says Brandon Avery, Converse’s head of global innovation. “We expect to see many of these designs come to life soon.”

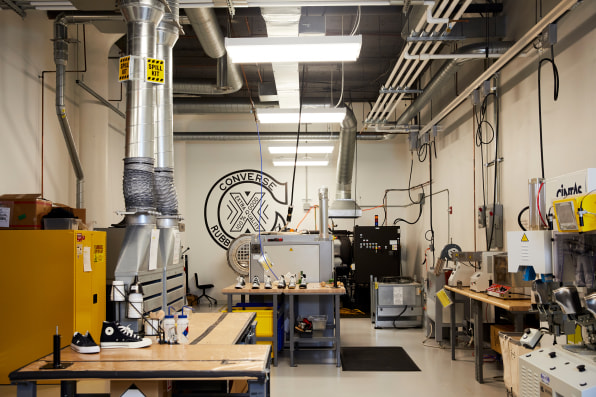

We’re in the Converse Concept Creation Center (C4 as the brand likes to call it) located in the Boston neighborhood of Charlestown, about 10 minutes from the brand’s headquarters. Converse moved into the building in 2015, taking over what used to be Schrafft’s chocolate factory. On humid days, you can catch a whiff of cocoa in the air.

In the world of sustainability, material innovations are a dime a dozen. These days you can find plastic made from algae and leather made from mushrooms and cacti. Many ideas never go beyond the conceptual, experimental stage; when they do, it takes a long time to turn them into a reality that can be scaled across the manufacturing process. But here at C4, Avery is cutting that time from years to months.

Over the past year, Avery and his team have launched collections of Chucks made from upcycled velvet and denim, soles made with specks of rubber waste, and a colorful new material made from scraps of fabric salvaged from factory floors. All of these collections scale into the tens of thousands of shoes.

Given the enormous extent of the fashion industry’s waste and consumers’ desire for more sustainable products, Converse’s effort to scale initiatives quickly allows the brand to stay competitive, especially in the sneaker industry where brands are launching new products every day that claim to be eco-friendly. Over time, as Converse relies increasingly on fashion waste and upcycled materials to make products, Avery believes this could reduce the brand’s production costs.

But rolling out so many trendy new products—even if they’re made from greener materials—also raises questions. Can products be truly sustainable if they’re encouraging us to consume, rather than prolong the life of products we already have?

A SIMPLE SHOE

I recently paid a visit to C4 toting an enormous black sweater. I loved its thickness and texture, but I never wore it because it was too large. So when Converse invited me into its C4 design studio to transform a beloved garment into a pair of Chucks, I immediately thought of that sweater.

The project is part of a broader thought experiment at Converse to explore the limits of what can be done with upcycling. Many Converse sneakers are still made with canvas fabric, unlike a number of other footwear brands whose products are made from synthetic materials. So it makes sense that designers at C4 have made upcycling clothing central to its design ethos. Over the past 12 months, the brand has made tens of thousands of its shoes from used garments—and my shoes are just another example of this work.

Part of the reason that it is so easy to transform new materials into Chuck Taylor sneakers is that the shoe design is relatively simple. Since Converse started producing Chucks a century ago, it has made them from a canvas upper and a rubber sole that are heated in an oven at nearly 340 degrees Fahrenheit to bond the materials together, a process known as vulcanizing. Then, only a few other design elements are added, like metal eyelets for the laces and a striped rubber lining called foxing. As a result, it’s relatively easy to swap out the canvas for other durable materials.

At C4, I work with a designer to create my Chucks. On a table, there are large stencils in the shape of the upper that I can put on top of the sweater to see what the shoe might look like. I pick out glittery gold laces, gold eyelets, and a thin gold strip of fabric for the back of the shoe for contrast. Converse then sent my selections along with my sweater to its factory in Vietnam, which transformed the pieces into my shoes and sent them back within weeks.

In many ways, my shoes are a microcosm of C4’s prototyping process, as it swaps a range of sustainable materials for the core components of a sneaker. Over the past few years, Avery’s team has discovered that it is possible to upcycle many kinds of used garments into Chuck Taylors, partnering with British vintage clothing retailer Beyond Retro to transform hundreds of pounds of jeans and velvet dresses into sneakers.

Beyond Retro sorts and cleans the old clothes and cuts them into rectangles the size of a shoe upper; then it sends the pieces to Converse’s factory in Vietnam to be made into sneakers. In upcoming years, Avery says Converse might launch collections using other materials widely available at vintage shops, like Hawaiian shirts and camo patterns from military uniforms. “Whenever we have an idea, we’re immediately in conversation with colleagues who specialize in logistics and supply chain so we can think about how to scale it up,” he says.

FUTURISTIC SHOES

The C4 team is focused on how to use other waste in the supply chain productively. For instance, there’s a lot of rubber that ends up on Converse’s factory floors. The team has found a way to break down these scraps into particles that can be remolded into the soles of shoes in a process they’re calling Max Grind. The final shoes can look identical to traditional sneakers. But Avery’s team liked the idea of creating a multicolored, speckled sole by keeping small pieces of rubber in their original color. This allows the shoe to more accurately reflect its recycled nature.

Another experiment involves collecting cloth scraps from factories and transforming them into a lightweight fluffy material, which is needle-punched into a felt. The team has called this process “scrap punch.” The final material has a pleasing, mottled texture that can feature a single color or many colors. “We don’t want to stray too far from the iconic Converse silhouettes that people love, but we’re also trying to inject newness,” Avery says.

But it’s also true that trends are part of the reason that the fashion industry is in an environmental crisis. Consumers are used to cycling through clothes and shoes quickly to keep up with what’s in style. Avery says that this is something his team thinks about. He points out that achieving durability isn’t just about creating products that are long-lasting. It’s about creating products that people are emotionally attached to. Allowing consumers to create customized sneakers could help give them a reason to keep the shoes longer.

The day I met Avery, he was wearing a pair of Chucks that are made from a baby blanket his mother had saved. I love the Chucks I created from the chunky black sweater. These are both examples of shoes that are unlikely to be thrown out when trends change.

Converse allows customers to personalize sneakers using its own library of materials, but it doesn’t yet have the infrastructure to let consumers send in their own materials to be transformed into shoes. Avery says that until then, the goal is to communicate that consumers should buy sneakers that reflect their own personalities, rather than just chasing trends.

“We’ve always been a brand that creatives have responded to because the Chuck is a blank canvas that allows them to express themselves,” he says. “We’re constantly thinking about creating shoes that are expressive and that hold meaning for different types of people.”

ENDS

—

This article first appeared https://www.fastcompany.com

Seeking to build and grow your brand using the force of consumer insight, strategic foresight, creative disruption and technology prowess? Talk to us at +971 50 6254340 or engage@groupisd.com or visit www.groupisd.com/story