Microsoft is heading the corporate charge into inclusive design. But even the company admits it has a lot to learn.

At first glance, you might think you walked into a suburban living room, or perhaps a hotel lounge. TVs, couches, and other comfortable seating fill the space, while a Rock Band kick pedal sits idly near the front door. But upon further study, the Microsoft Inclusive Tech Lab in Redmond, Washington—which opened in May 2022 as a space where Microsoft’s design team can develop new products, not simply for but withpeople with disabilities—is a meticulously crafted room, intended to welcome everyone, no matter their needs.

On the floor, crisscrossing tiles create a grid for easier cane navigation. In the corner, a fiber-optic octopus hangs from the ceiling, floating over a couch topped with richly textured pillows to ease neurodivergent people into the environment. Dimmable lights and sound-dampening paneling dot the ceiling and walls to mitigate overstimulation. And if you leave through the doors, down the hall you’ll find a bathroom equipped with adult-size changing tables, installed for some wheelchair users.[Image: Microsoft]

Six months ago, the room was nothing more than a campus lobby. A pool table sat in the middle of the room, and a few arcade cabinets were up against the wall. Now, that arcade is a small but dedicated space where the $1.9 trillion technology company (market cap)is developing new products and evangelizing the importance of designing a more accessible world to both its own 221,000 employees (as of June 30, 2022) and other corporations.[Image: Microsoft]

And evangelize, Microsoft does. Before the company invited me to be the first journalist inside the lab last October, it had already hosted representatives from Amazon, HBO, Nike, and T-Mobile. It welcomed designer Tommy Hilfiger and the musician Stone Gossard from Pearl Jam. It received government officials from Australia, Germany, Japan, and Singapore. Altogether, approximately 2,000 people in and outside the disability community have made a pilgrimage to the renovated space in 2022.

“It’s come a long way from the pool table,” says Panos Panay, chief product officer at Microsoft, with a laugh.

While the staff laments that some employees still treat the lab as a pass-through to the cafeteria, Microsoft is taking this moment to firmly establish itself as the corporate leader in the rapidly expanding space of inclusive design.

Inclusive design is the process of fashioning products and platforms alongside people with disabilities. It’s a technique that feeds into the broader umbrella of accessible or universal design. Accessible design programs are a ballooning practice across corporate America. Forrester estimates that people with disabilities are currently spending nearly $2 trillion a year, and companies courting the market are spending $10 billion on accessible design over the course of 2022. Today, surveying 505 companies from around the globe, Forrester finds that 60% of executives have committed to creating accessible products (up from 25% just a few years ago), and 27% of surveyed design professionals said their teams were going to hire roles in accessible and inclusive design in the next year.

“The work used to be very motivated by legal factors and increasing accessibility lawsuits,” says Gina Bhawalkar, principal analyst at Forrester. “The primary data we’re seeing [now]is about getting new customers, and attracting and retaining talent that cares about inclusion.”

Microsoft currently employs “hundreds of people who work on inclusive design and accessibility,” according to the company, and it has set up advisory boards on products for people with limited vision and hearing. Over the past several years, Microsoft has launched such watershed initiatives as its inclusive employment program, and in 2022 it spearheaded a new neurodivergent jobs marketplace called Neurodiversity Career Connector. That’s atop close relationships Microsoft maintains with half a dozen nonprofits, including AbleGamers, Special Effect, and the Cerebral Palsy Foundation—along with its own Ability Summit, which has operated for the past 12 years.

Yet, there’s a lot that Microsoft is struggling to talk about outside of its own mythos, like the way to use its inclusive products and the costs and revenue of its inclusive projects. Microsoft, it seems, has thought of everything. Well, almost. Developing traditional products is hard enough, but reimagining them as accessible products for the estimated one out of 10 people in the world with disabilities is proving to be a far more difficult task, given the eminently wide range of human needs. That’s a challenge even within the design of the lab itself, which is still a work in progress. At one point during my daylong visit in October, the lab’s director, Solomon Romney, gestures to a busy, striped wall.

“We’ve found that [this]pattern can be overstimulating for certain guests,” he says. “We’ve also heard that all the lights reflecting off the glass can be a bit much. So we’re thinking about ways we can help with that. But these are the kinds of conversations we have and the lessons we learn.”

Inclusion. Accessibility. These are design buzzwords today, but corporate interest in accessibility can be traced back to 1990, with the passing of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), which mandated baseline accessibility technical standards on public and commercial facilities, affecting the design of everything from building entries and water fountains to parking spots and carpet pile. While on-screen, digital designs weren’t explicitly included in the original ADA, in 1996 the Department of Justice defined the ADA to cover digital-product access; and every several years, as warranted, the ADA is expanded, mandating equal access to every manner of digital environment.

“I recall Microsoft Windows and Office always investing in accessibility and having people with direct experience of specific disabilities provide input and help design solutions,” says Tjeerd Hoek, a director of design on Windows in the ‘90s, who is now head of creative at Argodesign Amsterdam. “We also had to, because the government, Army, Navy, and Air Force were clients, and they required compliance to accessibility standards.”

To this day, ADA-related laws vary by region, and they tend to lack specific rules to designing websites, apps, and other digital products. Instead, the laws are driven by two vague but encompassing guidelines. “The law says you have to one, not discriminate, and two, effectively communicate,” says Lainey Feingold, the disabilities lawyer who pushed banks to install speech systems in ATMs in the ‘90s, and author of Structured Negotiation: A Winning Alternative to Lawsuits. “The only way [to satisfy both requirements]. . . is to make it accessible.”

Over the last decade in particular, Microsoft has increased its efforts to surpass any discernible ADA baseline. Following the Obama administration’s failed attempt to launch expanded web accessibility laws in 2010, companies including Facebook and Google have launched their own accessibility labs (Google just opened a new London lab this year).

“The labs are great, and they really are great if they’re done properly,” says says Lucy Greco, a web accessibility evangelist at UC Berkeley, who has been blind since birth. “The model I prefer is the model that companies like Amazon are using, where they have people with disabilities as part of the workforce, and there’s no ands, ifs, or buts about it. That is something Microsoft has been doing well, [too].” Greco’s criticism of most corporate labs is that they tend to be a place for able-bodied people to try out accessible technologies, such as screen readers, for themselves.

Microsoft’s lab has pushed the notion of accessibility further than its peers and has made a concerted effort to hire designers with disabilities. Even the fact that the lab—which can be filled with secret, prerelease products—has windows looking to the outside, instead of secure, opaque walls, signals an atypical openness of Microsoft’s design practice. Both literally and metaphorically.

Much of the credit to this new strategy belongs to the team under Albert Shum, Microsoft’s former corporate VP of design, experience, and devices, who had tasked his deputies with rethinking design at Microsoft in the 2010s. During this time, former Microsoft designers Kat Holmes and the late August de los Reyes codified the theory and practice of inclusive design.

While designers have long been thoughtful students of their intended audience, ultimately, a person who actually lives their life with anything ranging from a stutter to a power wheelchair will understand their distinct needs better than the most dedicated anthropologist. While universal or accessible design imagined a world built to accommodate people with disabilities, inclusive design argues that one must literally bring their subject into the design process to create solutions together. Ideally, what began as an accommodation will actually lead to better products for everyone. (The paradigmatic example? The OXO vegetable peeler.)ADVERTISEMENThttps://8901ff4dc0f5bb809c544d10a6255c94.safeframe.googlesyndication.com/safeframe/1-0-40/html/container.html

I’m sitting in the lab with Panay and Jenny Lay-Flurrie, Microsoft’s chief accessibility officer, awkwardly balancing on a stool with the variegated plastic patterning of a bendy straw, encircled by Microsoft designers and at least as many PR handlers. Panay is contemplative, self-effacing, and wearing all black, save for his olive green hiking boots. Lay-Flurrie toys with the fiber-optic octopus while casually listening in through her ASL interpreter.

Panay tells me that a decade ago his team was still concerned first and foremost with the reliability of their products—would they be durable enough to hold up on a day-to-day basis? The Microsoft team learned firsthand that if a product wasn’t built to last from its earliest steps in the design process, it most probably wouldn’t.

More recently, he says that their focus has shifted from starting with reliability (which is now table stakes) to two new priorities—sustainability and accessibility—each as impossible to add in the 11th hour of a product release as ruggedness.

In the 2010s, Microsoft began to bring people with varying disabilities into its own product labs to bake in accessibility from the get-go. Such strategy can be seen to this day within the Xbox interface (de los Reyes led the Xbox design team), which was constructed with large, easy-to-grok panels instead of tiny icons, cue-able with a click or voice command.

In 2016, Microsoft published an inclusive design tool kit, which, alongside Holmes’s book Mismatch, serve as corporate tomes of inclusive design. Microsoft itself used the methodology outlined in the tool kit—which includes everything from broad advice on how to connect with the disability community to finding research participants for specific exercises to audit a UX—to create its first inclusive piece of hardware, 2018’s Xbox Adaptive Controller.

Video game pads are wonders of modern engineering and design. Xbox controllers squeeze in 20 buttons for your fingers to reach (these controllers are so advanced that they have steered military drones and submarines), and they require fine motor control to operate. The Adaptive Controller whittled the design down to a flat board that can sit on your lap, with two giant buttons that are easier to strike. For everything else someone might want to do, the controller featured an unprecedented 19 ports on the back that allowed people to plug in any specialized button or sensor to control a game. Think, buttons you could strike with a foot or knee, or sensors that you could activate by puffing into a straw. The Xbox Adaptive Controller wasn’t just accessible for a single, or even a few, use cases, like an ergonomic cane might be; it was ostensibly designed for any possibility, through optional customization. Microsoft calls this approach “one size fits one.”

Microsoft embraced its more inclusive identity with a wave of saccharine marketing campaigns that began in 2018, and included a 2019 Super Bowl commercial produced by McCann. In the ad, children with disabilities detailed their joy gaming with Microsoft’s Adaptive Controller, while their parents discussed nervousness and fear of their children fitting in. The ads were widely celebrated, but were questioned by some in the disability community for framing people with disabilities as superheroes, and accessibility as a doe-eyed, childlike phenomenon.[Image: Microsoft]

While the Adaptive Controller won design awards (even the product packaging was designed with specialized pull tabs to open with a single hand or a mouth), Microsoft’s Disability Answer Desk—the company’s customer troubleshooting center with American Sign Language support that’s fielded a staggering 1.5 million calls over the last decade—was gathering less enthusiastic feedback. The problem: Microsoft’s own customers hadn’t been briefed on how the controller worked quite as well as the press.

“People didn’t understand that the real beauty of that product was . . . pieces that connected to it,” explains Kris Hunter, a senior director at Microsoft for devices user experience research and accessibility. “[People] want the hero shot, of course, right? But I do think we learned that we had to show the beauty of the adaptability of it. . . . You could just connect anything into that.” This communication gap around the Adaptive Controller was an even larger problem for caregivers, who were often the ones tasked with setting up the device but might not have the technical background to do it with ease.

This sort of lapse is why critics such as Henry Claypool, a consultant for the American Association of People with Disabilities, who advises for companies including General Motors, argues that Microsoft is falling short of its own claims. “Microsoft is an example of where a company has struck out as a leader to try to bring and instill this practice in their work, so devices can be born accessible,” he says. A bit later in our conversation, he qualifies that: “It’s clearly a growing practice [at the company], but just how deep it goes into the organization . . . is still pretty unclear.”

The Adaptive Controller has taught the company the importance of more supportive software and the necessity to film tutorials. But also that it still had strong biases that its technologies were easy to grasp. “Everything we’re doing now has an integration point from hardware and software,” says Panos.

That evolution is clear in Microsoft’s sequel to the Xbox Adaptive Controller, its Adaptive Accessories. The collection of mice and modular buttons are built for flexible use on a computer, tablet, or phone. Instead of being sized for a lap, they are tiny and portable (read a full breakdown here).

A 3D printing partnership with Shapeways allows people to order a variety of customized tops (and open CAD files even allow enterprising people to design their own). But as Gabi Michel, director of accessible accessories at Microsoft, demonstrates to me, the power of the accessories is largely in its software layer—the programmable macros. The Windows backend allows people to program a single button to complete complex tasks ranging from “copy and paste” to hyper specific jobs that can have a dozen or more steps, automatically juggling a maze of mouse clicks and enabling voice commands, even between apps.

Dave Dame, Microsoft’s director of accessibility, wheels up in a telepresence robot as Michel demonstrates the tool, explaining, “Really, what people with disabilities have in common with [everyone else]is we love to stay in flow when we’re doing our work.”

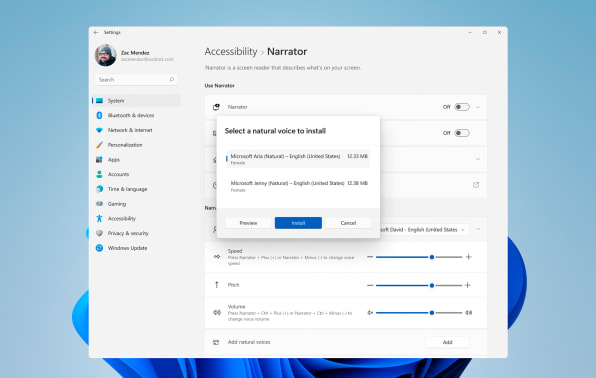

Microsoft also doesn’t want to make people who need access to these tools dig through layers of menus, which is why Windows advertises its improved accessibility from the moment you hit Start. The menu lists accessibility settings right at the top of its apps, and from there, it’s a tap to turn on audio transcription or verbal controls that make a computer usable.

“Before it was, ’We know you need something now. Here’s the maze!’” says Panay, who believes the new Start menu does a lot to fix this issue. “Elevating something like that into Windows? It seems trivial. It’s not. It’s complex. It challenges the UI.”

Experiencing demo after demo through my (admittedly able-bodied) eyes, Microsoft’s inclusive design work appears to be both effective and thoughtful. Yet, to gauge Microsoft’s impact through inclusive design—whether or not they’re improving the daily lives of actual customers—is a task so big that it’s nearly impossible to audit.

“We’d have to do an assessment, and lay out the metrics of ‘doing better,’” says Aimi Hamraie, associate professor and director of the Critical Design Lab at Vanderbilt University and author of Building Access: Universal Design and the Politics of Disability. “There can be things made and marketed in accessibility and inclusion that don’t do stuff people actually want. It makes it really challenging, even in an academic sense, to measure, Are things improving or not?”

Part of the issue is that designing for one is an impossibly large mantra. Even if Microsoft is listening closely to specific members of the disability community, it—like all groups of people—is too diverse to agree fully on how all things should be designed. And reaching customers and experts alike in this field is an ongoing challenge to Microsoft. I was surprised that in a handful of conversations with researchers and consultants in the disability community, all but one were unaware of Microsoft’s new space.

“They’ve never invited me to that lab,” says Greco, before tossing on a dollop of sarcasm. “I’m just a person who runs an accessibility program at a big university who happens to have a disability; why would I have to know what Microsoft is doing?” (In response to such criticisms, a Microsoft spokesperson clarified that, “For anyone interested in touring the space or learning more, we have our email address at the top of Microsoft Inclusive Tech Lab.)

Some have called the Adaptive Controller, with its large buttons (originally designed for amputees) infantilizing and overly specialized. It’s a perspective that might seem paradoxical to able-bodied people (shouldn’t products be designed to just work?), but to some in the disability community, initiatives like the Adaptive Controller can feel like superficial solutionism.

People with disabilities are often described as natural hackers because they’ve learned to adapt objects for their own needs. But that term doesn’t resonate with everyone. To some, a walker with tennis balls stuck to the bottom is a gross failure of companies to properly design a walker that can glide smoothly on its own; whereas to others, those tennis balls are a point of pride, celebrating the ingenuity of people with disabilities to thrive in a world that’s so often ignored their needs.

“[DIY products] are a way we pass innovation and build community,” explains Hamraie. “We say, ‘we got this thing at the dollar store and [transformed]it into this other thing—and you can, too!’ But not everyone wants to do that.”

Indeed, not everyone does, which is why Greco approaches the topic more bluntly. “Somebody who generalizes and says people with disabilities are natural hackers? Bullshit,” she says. “People are hackers or people are not hackers. If they happen to have a disability and fall into the hacker space, they might be in a better place when they use inaccessible technologies.”

While Microsoft puts incredible effort into marketing its inclusive design programs, the company has always shied away from questions about the profitability of its accessible initiatives. When I ask Lay-Flurrie about the profitability of the lab and Microsoft’s accessible initiatives, her friendly countenance melts away, and her jaw juts out in advertised disgust.

“We don’t do this for ROI,” she says. “And I will just say, this question comes up, candidly, a little too much.”

But the question remains valid to researchers in the disability community, because profitability is a capitalist placeholder for that word Microsoft used to be so focused on: reliability.

“Society needs to know, are these things being created financially solvent?” says Hamraie.

On one hand, both McKinsey and Forrester have both pointed to the trillions of dollars in consumer spending up for grabs in building products for the disability community. On the other, Microsoft is carefully implying that it’s losing money, or at least doesn’t care if these programs ever happen to turn a profit.

Yet, financial solvency is the only dependable way that accessible design can scale. That’s true for both inclusively designed products and the labs that produced them. Microsoft—which is working hard to lead the corporate conversation around accessibility—also owes it to the community to disclose the financial stability of the operation, both so that the disability community understands the costs of these programs long term, and so corporations modeling Microsoft can properly assess and plan inclusivity projects of their own.

Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella is a champion of inclusivity, and published his own 2017 letter detailing his life with his son Zain Nadella, who lived with cerebral palsy since birth and passed away in March 2022. Yet, one only needs to glance over to Elon Musk’s takeover of Twitter to see how a shift in ownership can completely alter a company’s civil rights priorities, especially if certain programs aren’t profitable. Case in point: The Adaptive Controller itself was almost canceled due to budget balancing at Microsoft.

Microsoft is deep enough into its own accessibility initiatives that a Twitter-like human rights meltdown, which has emboldened racism and Nazism over the past few weeks, seems hard to imagine. But many companies emulating Microsoft’s inclusivity efforts don’t necessarily have institutional momentum on their side, nor do they have the $100 billion pile of cash that Microsoft does to ride out any economic tumult. It’s easy for companies to play the good guy when things are going well, and harder when they aren’t.

History also teaches us that if accessible products aren’t profitable, they don’t stick around for long. Hamraie points to thermostats developed in the 1970s with big buttons and displays, which were easier to read and use for people with vision issues and arthritis, but disappeared from the market. Meanwhile, they point to the ergonomic task chairs born in corporate environments in the 1980s, designed to ease one’s body to increase productivity, and the stretchy pants of athleisure that can squeeze onto more body types, as examples of accessible ideas that have stuck around because they were flexible. Accessibility has always had roots in industrial capitalism, and Microsoft is not immune to this reality.

“It’s why we have ergonomic chairs at the workplace but not our dinner tables,” says Hamraie.

Yet, for any lingering skepticism about Microsoft’s inclusive design initiatives, those efforts have been contagious across the business world. Lay-Flurrie says that she talks to peers at Apple and Google “every few days,” and the fruits of those conversations can be seen in a new joint research project that also includes Meta and Amazon to improve speech recognition for people with speaking impairments.

Ayelet Winer, senior technical product manager at T-Mobile, has toured design conferences for the past several years, studying the ins and outs of inclusive and accessible design to expand the wireless carrier’s accessibility programming. She calls Microsoft’s lab the “gold standard” in the industry and considers it a place where the sharp elbows of capitalism are padded so that companies can pursue shared ideals.

While Winer is currently planning her own inclusive design lab at T-Mobile, she admits that just three years ago, when she was tasked by her boss to build out T-Mobile’s accessibility efforts, she knew nothing on the topic. And when she saw Lay-Flurrie speaking on stage during that time, upon hearing that Microsoft had such an expansive inclusivity team, Winer called her manager in a panic.

“I’m like, ‘Oh my god, I will never be able to do that,’” she recalls. “Today, we have a much bigger [accessibility]team. We are building our own training. We have best practices. We have processes people are following. We have experienced a huge, huge growth. But it all started with me looking at Microsoft, terrified.”

ENDS

—

This article first appeared https://www.fastcompany.com

Seeking to build and grow your brand using the force of consumer insight, strategic foresight, creative disruption and technology prowess? Talk to us at +971 50 6254340 or engage@groupisd.com or visit www.groupisd.com/story