A GOOGLE VENTURES-BACKED STARTUP PARTNERS WITH NASA, MICROSOFT, AND SATELLITE MAKERS ON A CHILDREN’S BOOK OF GALACTIC AMBITION.

It began as an audacious side project. Three dads and an uncle got together to make a personalized book for children. The Little Boy/Girl Who Lost His/Her Name, in which any child’s name, thanks to some nifty algorithms, dictates the plot turns, became a surprise hit. It was the bestselling picture book in the U.K. last year. This week, it topped a million copies sold worldwide (to actual customers, mind you, not retailers).

How do you follow up that sort of debut? Lost My Name, the London startup that grew out of the project—part tech company, part book publisher, and backed by Google Ventures and others—just launched its second personalized tale, The Incredible Intergalactic Journey Home. “I like to think it’s the most technically ambitious book ever created,” says co-founder Asi Sharabi.

That’s quite a claim. But he makes a compelling case, one that would have certainly blown the mind of Johannes Gutenberg.

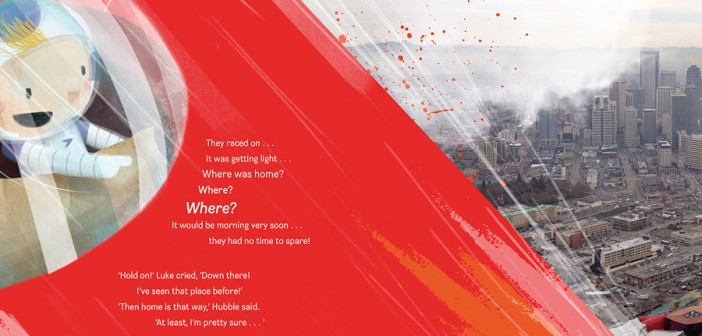

This time, a lost boy or girl navigates his or her way from outer space back home. Spoiler alert: to the reader’s actual home. The wayward space ship swoops into his or her city and arrives in the child’s neighborhood. The image, the book’s big reveal, incorporates the corresponding satellite photos. That degree of personalization required even more algorithms and developers than Lost My Name’s first book, along with help from NASA, Microsoft, satellite makers, and other unlikely children’s book partners.

“Everything was about 10 times more complex than we imagined,” says Sharabi, a former marketing executive. “There was no benchmark. No one had done any of this before.”

Today, The Incredible Intergalactic Journey Home journeys into space. It’s one of seven books aboard a rocket bound for the International Space Station as part of the Global Space Education Foundation’s Story Time from Space program. Astronauts record themselves reading the stories in zero gravity. Teachers nationwide play the videos for students.

When I visited Lost My Name’s East London offices last summer, the book was still a work in progress. Walls and cubicles featured pencil sketches, illustrations, and storyboards by co-founder Pedro Serapicos, the company’s resident artist. A little boy or girl named after the child and accompanied by a lemonade-slurping robot named Hubble was racing by meteors and planets and eventually standing outside a front door featuring the child’s actual house number.

Lost My Name’s co-founders: (from left) Tal Oron, Asi Sharabi, Pedro Serapicos, and David Cadji-Newby.

To the Lost My Name team, personalization should be an emotionally resonate experience that’s organic to the story, not a mere gimmick. Their first book followed the reader’s elaborate search for his or her name. For the new book, says Sharabi, “We started by asking what are the other universally personal elements that are a strong part of a child’s identity? Home and locality. My place in the universe. Ultimately, it’s this sense of belonging.”

The company held a hackathon where more than a dozen developers brainstormed about possible technology and data to explore locality, from the position of satellites to satellite images of the Earth. “We wanted the wildest, craziest ideas for personalization, but we don’t want to use technology for the sake of technology,” Sharabi says. “We go back to the absolute roots of what makes a brilliant story.”

David Cadji-Newby, a former BBC comedy writer, is the author and official story guardian. “He’s the one who says, ‘Guys, this may not have been done before, but it doesn’t serve the narrative,’ ” says Sharabi. “The goal was adding to the story different magic moments enabled by technology.”

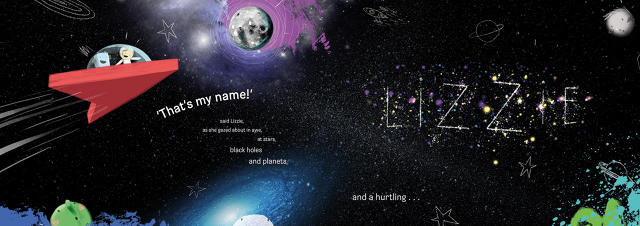

The magic moments in Intergalactic Journey involve personalization. Spelling a child’s name (he or she is the protagonist) at the beginning in actual stars “connect the dots”-style. (“With our algorithm, two kids with the same name have different constellations,” he says.) Displaying the Earth at the angle that corresponds to where the child lives and using the appropriate country’s flag on the spaceship. Displaying landmarks in his or her hometown on a two-page spread, which required building a database of thousands of geo-coded landmarks. (“This is the key thing, that a kid in Philly or Toronto or Norway gets the most contextual, familiar landmark to where they live,” he says.)

Behind each of those customized elements is technology built by the Lost My Name team, which included 14 developers compared to one on the first book. Their biggest challenge was the two-page aerial photo of a child’s neighborhood at the end. After securing rights to the images with satellite companies, they had to ensure that the satellite images matched the child’s address. They tested 35,000 addresses in the U.S. and U.K., the first two markets where the book is available, reducing the error rate to less than 1%.

Each $30 book is made to order through Lost My Name’s site. Customers provide a child’s name, gender, and address, choose a skin color and outfit, and confirm the location of the home on a satellite photo.

The team also had to resolve the inconsistency of satellite images, which consist of more than 200 map tiles stitched together. “It took us two months to write the algorithm to identify and fix any anomalies, like a damaged tile or a problem with pixels,” says Sharabi.

In the end, none of the technical hurdles matter to Lost My Name’s audience. The story of a fanciful journey from space to their own home has to engage children, whether their parents are reading it at bedtime or an astronaut is reading it from somewhere in Earth’s orbit. “We are keen to deliver more magic,” says Sharabi. “We’ve gone from zero expectations to a national bestseller, and all eyes are on us.”

[All images: courtesy of Lost My Name]