While other software giants are simplifying their branding, Mailchimp is keeping it quirky.

As companies grow up, their branding usually does, too. That often means that the initial quirkiness of a startup logo fades into the slick, streamlined branding you see everywhere today–like that same sans serif font that has become the basis for Google, Airbnb, and Pinterest’s wordmarks.

The marketing company Mailchimp, which today is announcing a complete rebrand, could have easily given up the quirkiness that defined its branding as a young company the way many other giants have. Instead, with the help of branding agency Collins, Mailchimp is doubling down. It’s keeping its logo-cum-mascot Freddie the Chimp, for starters, and using an analog typeface from the 1920s as its new typeface, and illustrating its new brand with a series of almost childlike drawings that look unpolished and rough by design. Weird branding is alive and well in the tech industry.

Mailchimp itself was responsible for pioneering the kind of friendly, humorous design you see everywhere in tech nowadays, which was radical when the company first launched in 2001. Perhaps most emblematic are the company’s ubiquitous podcast commercials, which poked fun at its name: “Mail . . . kimp?” It’s hard to imagine Google making fun of its own name in commercials. But that was Mailchimp, with its primate logo and curly, seemingly handwritten wordmark.

“That wry sense of humor is an authentic part of their brand,” says Ben Crick, a creative director at Collins who worked on the branding. “They have more of a right to it than most of the tech companies that rely on humor.”That winking humor, along with playful illustrations that are meant to demystify what a tech company does, is commonplace among startups these days. “It’s the de facto way to look if you’re a tech company,” says Angie Shih, a strategist at Collins. “The trajectory of every company is that you’re quirky, friendly, approachable, and when you become a massive company with a lot of employees, you become austere, sterile.”

Mailchimp wanted to keep its quirk and eschew the traditional logo trajectory that Shih references, where large tech companies opt for the slick and seamless over the human. But the company did want to rebrand for similar reasons that others do: It has grown significantly since its founding 17 years ago. The company sends about a billion emails per day, and as of 2017, it was adding 14,000 new customers per day.

“As we evolve as a company and are offering these different services and features, we need to evolve our brand and our visual language as well,” Gene Lee, Mailchimp’s vice president of design, tells Fast Company. Features now include marketing automation software that’s more sophisticated than the email building software that the company has been known for.

And among smaller companies that haven’t yet gone corporate, the quirky, playful brand is very in right now–making it harder for Mailchimp to stand out. “Part of the challenge with creating a visual language and a system is, these days, it’s hard to come up with something that nobody has seen before,” Lee says.

The solution? Nothing about Mailchimp’s new brand uses slick design to point to the company’s maturity. Instead, Collins maintained nearly everything about Freddie the chimp, just simplifying the image slightly so that it would work better across a range of different sizes and situations. (“He got a haircut,” Crick says.) The designers created a typeface to use for the wordmark, and updated the 1920s, pre-digital typeface Cooper Black for use elsewhere, with the idea that it would make the brand feel more humanistic.

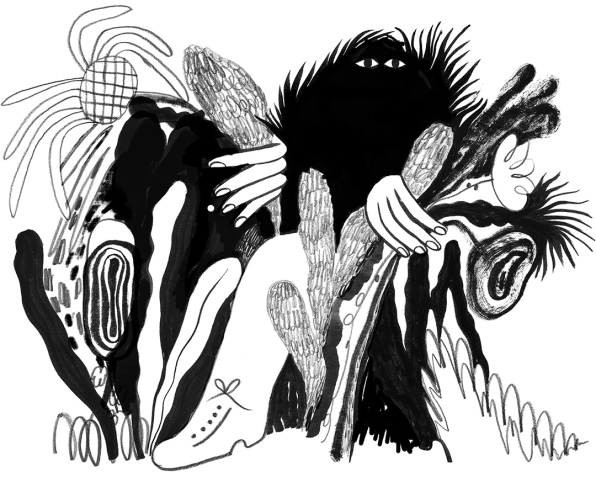

Most striking are the illustrations on the company’s new website and inside of its web platform. Mailchimp worked with both internal illustrators and artists from around the world to create drawings with a sense of perspective that’s slightly off-kilter–one that makes them appear like they were drawn by either a famed contemporary artist or a kindergartner. There’s a person with five legs representing Mailchimp’s automation features, a misshapen hand balancing a stack of objects illustrating how quickly users can create with Mailchimp, and a giant personified mushroom acting like an umbrella for a host of smaller fungi to represent business growth. On the company’s new website, a human figure with a gigantic arm, who is adding the final piece to almost-completed puzzle, symbolizes Mailchimp’s optimization tools. An illustration accompanying a message to welcome new subscribers shows a group of oddball birds sitting with a person on the pinkie finger of a giant hand. It’s the kind of weirdness you wouldn’t expect from a company with Mailchimp’s success–last year it brought in $525 million in revenue–and that’s exactly the point.

“Ultimately, the goal is to make Mailchimp a beacon for its own customers, who are growing brands trying to figure out how to speak to their people,” Shih says. “[They’re] hoping to send a message to these companies that success doesn’t mean erasing your peculiarities and idiosyncrasies. It’s about amplifying them. That’s how you stand out and connect with everyone.”Whether the branding’s strangeness works is another question. Part of the goal was to attract larger businesses, which might be put off by some of the illustrations’ childlike elements. But in staying strange–and, they say, true to themselves–Mailchimp is challenging the typical paradigm for tech branding today.

–

This article first appeared in www.fastcompany.com

Seeking to build and grow your brand using the force of consumer insight, strategic foresight, creative disruption and technology prowess? Talk to us at +9714 3867728 or mail: info@groupisd.com or visit www.groupisd.com