Our industry used to be full of people who had an instinct, who just knew, writes Russell Ramsey.

Over the past six years, boy band One Direction have sold more than 50 million albums and millions more singles.

Last year, they sold more than two-and-a-half-million concert tickets globally – more than any other artist. But does anyone remember that they only came third on The X Factor? Let’s think about that for a minute.

A research group with ten million participants deemed One Direction to be only the third-best option they were presented with. In the marketing world, One Direction would have been consigned to the dustbin with a result like that. The people have spoken and this is their conclusion. The sample size would be beyond reproach.

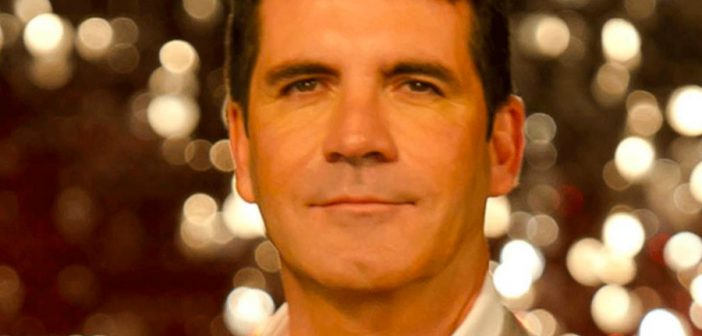

Arguing with the result would be futile. “Bombed in research” would have been the resulting headline. But guess what? When they didn’t win, they were immediately signed up by Simon Cowell. Because Cowell knew they were going to be big.

He knew the public would eventually fall in love with them. That’s his skill. The uncanny knack of knowing the public’s mind better than they do themselves. He also has a belief in his own judgment. His subjective view overruled the evidence.

In the marketing world, however, we’ve stopped trusting the people with the knack. The people who just know, the people with an instinct. The people with the skill for knowing what will capture imagination. Advertising was once full of them. Creatives, planners, directors, composers. All with a special skill, a knack. An indescribable ability to make a decision based on their experience, knowledge and instinct. They came up with the unexpected and the inspirational because they weren’t following the rules.

He knew the public would eventually fall in love with them. That’s his skill. The uncanny knack of knowing the public’s mind better than they do themselves.

If you’ve seen the movie Steve Jobs, you’ll know that he ignored the research and data that showed people wanted an open system, a system they could plug their other devices into. Jobs wanted a closed system but he knew – he had the feeling – that actually they would learn to love a system that was pure and Apple-centric.

He backed his own judgment. He knew the consumer better than they knew themselves. But, these days, we’ve abdicated responsibility for making decisions. We think we don’t need to any more. Somehow, the decision will be made for us further down the process by the data or the research.

I once sat in a meeting with a senior marketing director, all of his marketing team and some of the finest brains advertising has to offer, only for the marketing director to announce that no-one in the room was capable of deciding – only the consumer could decide.

The danger with this approach is that if we’re not making the decisions, then we start not bothering to have opinions. We drift into producing endless options that get served up to consumers and analysts without needing to have a point of view.

More recently, we’ve moved on from just letting the consumer decide and we’re now also letting the data decide. The question is: does data have the knack? Does data have that unidentifiable skill that comes from the heart as much as the brain?

In February, data analysts wrongly predicted that The Revenant would win the Oscar for Best Picture. They concluded that it had an 84% likelihood of victory.

“We take the human element out and just look at the data” was the proud declaration from Nirav Patel of Cognizant, an IT consultant company. He actually believed that taking emotion out of decision-making was a desirable thing.

So even in an artistic environment, eliminating subjectivity was his holy grail. On the other hand, one of the major betting companies correctly predicted that Spotlight would win, even though Patel’s data analysis had only given it a 7% chance of winning. Its secret? “We watched the films.”

The company’s subjective judgment was that Spotlight was the best, most engaging film and it was prepared to back its judgment on it. If we believe in creativity, we should also believe in the people who have it and not default to computers telling us how to edit pre-roll films, for example.

Give me someone with the knack over someone or something with a pile of research and data any day. Give me more Simon Cowells.

This article first appeared in www.campaignlive.co.uk