A fascinating new book reveals the visual culture of 19th and early 20th century secret societies.

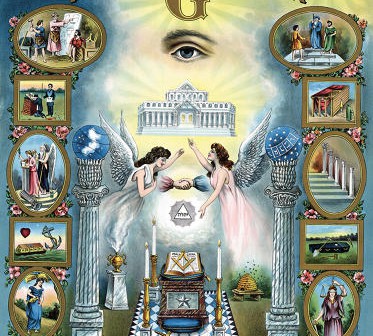

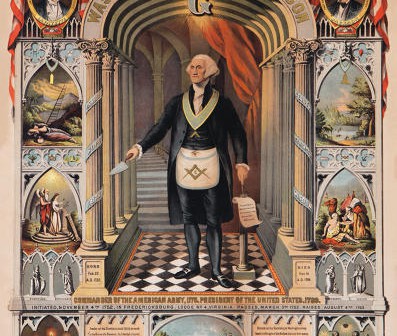

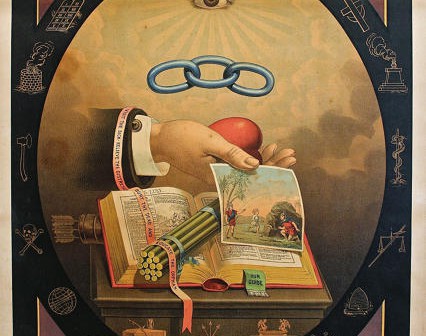

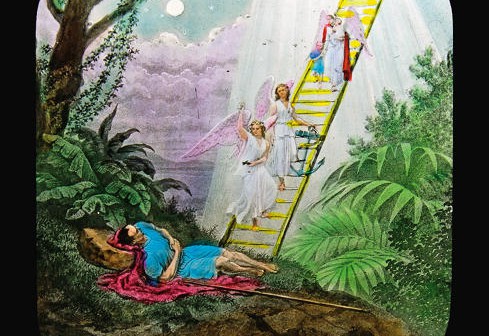

The visual culture of these groups was complex and vivid, to say the least. In As Above, So Below, art collector Bruce Lee Webb and art historian Lynne Adele lift the veil on the mysterious visual culture of dozens upon dozens of different orders that sprang up in the 1800s and early 1900s. Webb is a longtime Odd Fellow and arguably the foremost collector of artifacts and art from fraternal orders (Webb also runs the outsider art-focused Webb Gallery in Waxahachie, Texas, with his wife, Julie), and the book catalogs his trove.

David Byrne, himself a collector of these objects, wrote the foreword. “Was there another America behind the America that we knew?” Byrne wonders in his introduction, describing Webb’s collection as “a crack in the wall” where “some paraphernalia was being secreted from the secret America.”

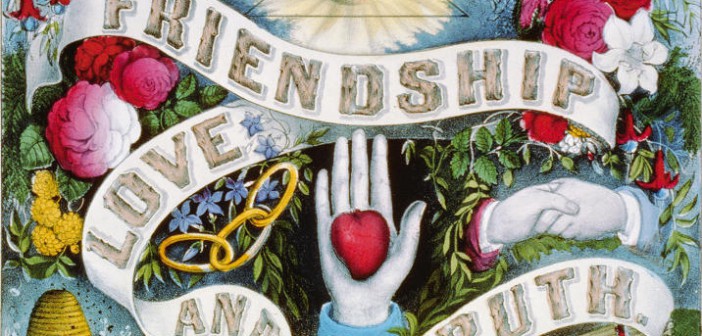

Because there’s no real historical account or documentation of these societies, it’s easy to forget the way they shaped American life. But they once boomed across the country, first in the years after the Civil War, and later as westward expansion populated the American West. By the late 1800s, there were 70,000 different lodges spread across the country, the authors write. They focused on raising money for charity, developing business networks, and strengthening fellowship among members (some also had an unsavorylegacy of discrimination, whether based on gender, religion, or race). All had an uncanny talent for creating elaborate regalia, signage, and aesthetic culture that helped attract new members—no matter how “secret” their activities really were.

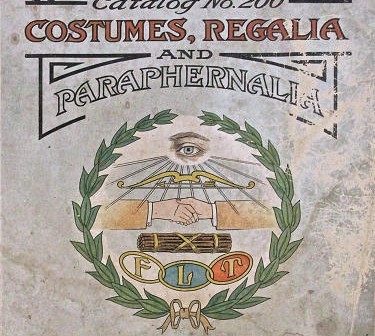

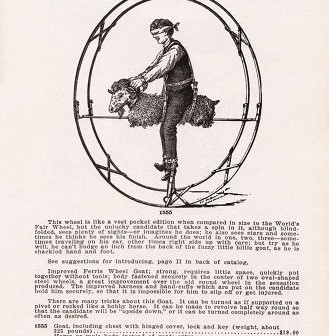

“It was branding,” says Webb when I ask if that definition fits. “A lot of the designs were copied and just changed slightly in the catalogs the companies would produce.”

The culture of fraternal orders necessitated a whole manufacturing industry. They produced elaborate catalogs and marketed their wares aggressively. In at least one case, the founders of a new fraternal order started a company to supply goods to new lodges, a clever business model. During the Civil War, when demand dipped, Webb says some factories selling lodge gear simply switched over to selling military supplies instead. When members came back from the war, the lodge catalogs reappeared. Eventually, the industry collapsed in the mid-20th century. Today, few of these companies exist—the ones that do make graduation caps and gowns, fezzes, or uniforms for school bands.

Both Webb and Adele say that there’s been a resurgence of interest in fraternal orders, though. “It’s kind of anti-technology, because you can’t use technology to make someone a Mason or an Odd Fellow,” says Webb. Byrne writes that he’s “envious” of the golden age. In his foreword, he sums up both the bizarre visual culture and sociogram of this era of American history: “Can you imagine me suggesting to my local bank manager that he and I put on some freaky outfits, and that he should hold the fake sword and I’ll hold the staff with the snake on it?”