The focus of today’s sermon will be brand babble and the widespread and usually silly attribution of human characteristics to brands by marketers.

As I’m sure you’re well-aware, we all want to have “relationships” with brands, and be part of a brand’s “tribe” or “community” and “co-create” with brands, and understand “brand meaning,” and of course, respect and trust their “brand purpose.”

What? You don’t?

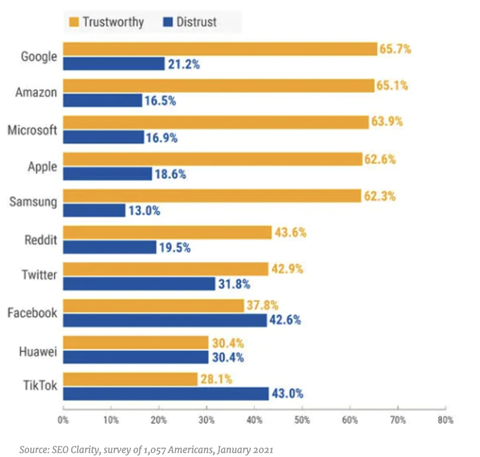

Our first stop on this tour de farce, is this piece written by Mark Ritson. Facebook is probably the least trusted brand in the universe (the “metaverse” notwithstanding.)

Ritson says, “Facebook repeatedly ranks low in consumer trust surveys, yet user growth continues, revealing the idea of trust in brands as anthropomorphic nonsense.”

A piece published this week in MediaPost had this to say…

“Consumers love to hate Facebook, but they don’t stop using it. The company just keeps growing. Daily active users, to cite one metric, were 1.91 billion on average for June 2021, an increase of 7% year-over-year. Headcount at the company was 63,404 as of June 30, 2021, an increase of 21% year-over-year.”

The idea that the brands we use are intensely important to us and we spend time and energy sussing out their meaning and trustworthiness is a deeply embedded marketing fantasy. For most people, their “relationship” with most of the brands they buy is shallow, transactional, and contingent. Brands are not nearly as important or meaningful to consumers as most marketers would like them to be.

Marketers have the naive but apparently fact-resistant belief that customers care deeply about what they use, and buy according to a logical or emotional comparison of what they want and what the brand says it is “about.” Sometimes they do. But mostly they don’t.

Any scientific, non-ideological interpretation of consumer behavior can lead to only one conclusion: All other things being equal, most people buy most brands in most categories because they are the most familiar. Not because they are the most deeply understood or the most personally meaningful. The leading brands in virtually every category tend to be the most familiar, regardless of what the brand babblers say about their meaning.

Let’s make this even simpler. People are mostly too busy, too lazy, or too indifferent to give 2/5ths of a flying shit about the “meaning” of all the stuff they buy. Mostly, they buy on auto-pilot from familiar brands they feel comfortable with.

“Naive and Unjustified”

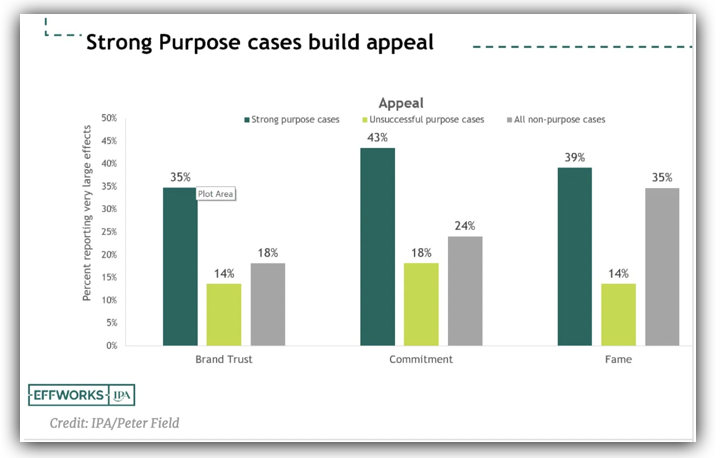

Next we move on to one of my favorite topics, brand purpose.

As regular readers know, here at The Ad Contrarian Worldwide Global Headquarters, we are fully in favor of brands doing good things, but very skeptical of “brand purpose” as a marketing tactic. We want corporations to do the right thing because it’s the right thing to do. Not because they can make marketing hay by rubbing our noses in their virtue. Consequently, we have been very vocal and critical of the hypocrisy that pervades the whole “brand purpose” advertising craze.

An article in MarketingWeek this week caught our attention. It was headlined: Criticism of Brand Purpose Is ‘Naïve and Unjustified’, Claims Peter Field.

Peter Field is a very highly-regarded British researcher (who along with the great Les Binet) has done some breakthrough work on advertising effectiveness. While we have high regard for Peter, we have not always been comfortable with his methodology.

The article in question says that Field calls for an end to “vitriolic criticism piled on brand purpose by some industry commentators and practitioners (that’s me!) having found through new research that well-executed purpose campaigns deliver superior effectiveness on a number of key business measures.”

When you see vague terms like “superior effectiveness” the first question you have to ask is, superior to what?

Here is a chart that neatly summarizes the findings of the research in question. In a minute we’ll see how the ‘superior to what? ‘ question becomes very germane.

We believe this research proves exactly the opposite of the impression left by the tone of the article. Before we make our case, let’s issue this disclaimer. We are basing our opinion on the reporting of the research by the writer of the article. Peter has access to the primary responses and we don’t. Nevertheless…

We believe the key finding of the research, as quoted from the article, is this: “Initially, the findings look bad for brand purpose advocates. The average number of ‘very large business effects’ for all non-purpose campaigns stands at 1.6, while for brand purpose campaigns this figure drops to a markedly lower 1.1.”

In other words, comparing apples to apples, brand purpose campaigns perform “markedly lower” than non-purpose campaigns. This is no surprise to us “vitriolic” critics of brand purpose advertising.

But then Peter does a little research sleight-of-hand that would be laughed out of any legitimate research facility. He cherry picks only the strong (i.e., most successful) purpose campaigns and compares them to all non-purpose campaigns. This is what happens when researchers are looking for an outcome, rather than the truth.

If you want to know the comparative effectiveness of all purpose campaigns, you compare them to all non-purpose campaigns. If you want to know the comparative effectiveness of strong purpose campaigns you compare them to strong non-purpose campaigns. But if you want to find an outcome you’re looking for, you compare strong purpose campaigns to all non-purpose campaigns.

Baseball fans, here’s an analogy. Let’s say you want to find out who hits better, left-handed hitters or right-handed hitters. So you do some research and you find that overall lefties bat .270 and righties bat .250 (btw, I’m making these numbers up.) But, dammit, you wanted righties to bat better. So you do a little trick and you cherry pick the top 50 righties and find that on average they bat .290. Now you can say “well-performing righties deliver superior effectiveness on a number of key batting measures.”

Belief that the research in question demonstrates that brand purpose advertising is anything but less effective than non-purpose advertising is “naive and unjustified.”

(BTW, I like and admire Peter, but in baseball terms, I call ’em as I see ’em.)

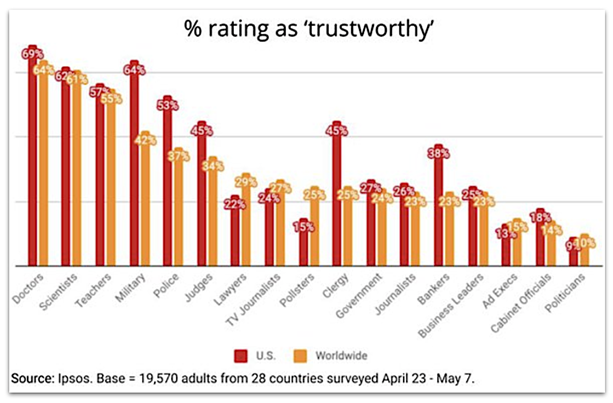

Falling Behind: Ad People No Longer Least Trusted

A study of the world’s least trusted professions came up with some unsettling news for us this week. We are no longer the least trusted profession in the world!

While previous studies have placed us in the #1 least trusted position, according to consumer research firm Ipsos this year the least trusted professions are government officials and politicians (which, as far as I can tell, are pretty much the same thing.) So we can no longer brag about being #1. We’re going to have to qualify our world-leading status in the following way — we’re the least trusted non-politicians in the world. Not perfect, but still impressive.

Fake It ‘Til You…. Well, Forever

Among the start-up tech set, one of the philosophies that has dominated for the past two decades is the extremely annoying “fake it til you make it.”

This is just a very cute way of saying, lie, cheat, and commit fraud until you either get healthy or get caught. By then, if you get caught, you’ll either be out of business or be big enough to hire a suite of lawyers who’ll con the government into a cozy settlement. But the chances of being prosecuted for your fraud? Zilch on a stick.

We’re all familiar with how deeply this philosophy cuts in techland from the one case that actually is being prosecuted — the Theranos case.

Steve Goldstein does a good job this week in explaining how “fake it til you make it” is also alive and well in online media. Steve takes us through the alarming case of adland darling Oxy Media and explains that in the super-hyped world of podcasting, as in all online media, audience metrics are both critically important and highly unreliable.

Can This Be True?

And speaking of fraud…. an article appeared in Ars Technica (an online magazine owned by Condé Nast) this week that has me scratching my head. It’s one of those conspiracy theory stories that makes a conspiracy theory hater think that maybe there was a conspiracy.

It concerns a hacker named Robert Willis (once known as Hacker X) who claims he created a huge network of interlocking websites that produced false and inflammatory misinformation during the 2016 presidential election and reached millions of people daily. His activities were so successful, he claims, that his own father still believes the bullshit he made up, even after he told him he made it up.

Ars Technica claims it vetted this guy’s story every possible way, and it checks out. The problem is, they won’t name the apparently well-known media company that hired Willis to do his dirty work. That’s a major black hole in an otherwise fascinating story. You might want to read it and draw your own conclusions. If it’s true, it’s a whopper. h/t Bob Sproul

Tweet of the Week

Last week, in a piece about the deafening silence of the ad industry during the ongoing Facebook scandal, I wrote, “(The) reason I believe our industry has been silent is that Facebook has bought and ‘owns’ the industry. No one in a position of authority has the balls to call them out.”

This week, John McCarthy, Media Editor at ad industry pub, The Drum, tweeted this out. I rest my case.

Today’s Lessons For Agencies

I’m finally getting around to reading “Thinking Fast And Slow” by Nobelist Daniel Kahneman. It’s totally brilliant and has a lot of ideas that are important to advertising practitioners.

One of the things I love about the book is that it seems to be confirming so many of my beliefs about advertising. Kahneman would call this “confirmation bias.”

Here are two tidbits from the book that can be helpful to agencies.

1. When you’re showing your reel or presenting new concepts, do you lead with your best stuff or save the best for last? I’ll give you 5 seconds to decide…5…4…3…2…1…

When I was in the agency business and we were making presentations I always insisted on leading off with the best we had. It turns out that for once in my life I was right. Kahneman clearly illustrates how “the halo effect” works and why you should always lead with the best you’ve got.

2. When you’re pitching, clients sometimes find it too difficult to make a decision based on which agency is best. So they unconsciously step down the decision and make it about something else – like which agency they like better. The moral here: Keep the unpleasant people out of the pitch meetings.

Seeking to build and grow your brand using the force of consumer insight, strategic foresight, creative disruption and technology prowess? Talk to us at +971 50 6254340 or mail: engage@groupisd.com or visit www.groupisd.com/story