Today’s films are brimming with products from big-name brands. How exactly do these partnerships work?

In the 2000 film Cast Away, Tom Hanks’ co-star isn’t Leonardo DiCaprio, Meg Ryan, or some other A-list actor.

It’s a volleyball, courtesy of Wilson Sporting Goods.

Throughout the film, the volleyball enjoys 10.5 minutes of screen time worth an estimated $1.85m+ in advertising value. And for this exposure, Wilson paid a grand total of $0.

Each year, hundreds of brands — cars, computers, clothing, kitchen appliances, and lawn chairs — grace the silver screen.

Sometimes brand appearances are overbearing (think a 30-second-long glamour shot of a Lexus driving down the coast); other times, they’re so subtle you might miss them if you blink.

But how do these brands end up in major motion pictures? What do the economics of these deals look like on the back end? And is this an effective form of marketing?

A mutually beneficial exchange

A frequent misconception is that all brands pay a fortune to appear on the silver screen. In some cases this is certainly true:

- Harley-Davidson paid $10m to get its electric motorcycle featured in Marvel’s Avengers: Age Of Ultron (2015).

- Heineken shelled out an estimated $45m for 7 seconds of screen time in the James Bond film Skyfall (2012).

- BMW plunked down ~$110m to supply cars for GoldenEye (1995), Tomorrow Never Dies (1997), and The World is Not Enough (1999) before Aston Martin outbid them with a ~$140m offer for Die Another Day (2002).

- More than 100 brands (including Gillette, Nokia, and Carl’s Junior) offered a combined $160m to be featured in Man of Steel (2013).

Heineken’s $45m James Bond deal came with the rights to cross-promote the beer in commercials starring the leading man, Daniel Craig (via Heineken)

These big-money deals include a slew of other elements, like verbal cues written into the script (“Boy, I sure could go for a nice, ice-cold Budweiser!”), a guaranteed amount of screen time, and the rights to run cross-promotional advertisements with the film’s leading actor.

But in the majority of cases, there is no cash exchanged at all between the brand and Hollywood: Producers need props, and brands are happy to loan them out at no cost in exchange for exposure.

The rationale for these arrangements is simple: Movies are pretty damn expensive.

On average, a major studio film costs around $65m to produce, not including marketing and distribution. The largest chunk of that is general production costs, which include set design, props, and wardrobe.

For action films, the prop budget alone can stretch into the millions.

The Fast & Furious franchise, for instance, wrecked a total of 1,487 cars over its first 7 movies. Even at a modest estimate of $20k/car, that amounts to $30m in prop costs.

Property masters (the folks in charge of props) are on a constant quest to cut down budgets — and product placement can be a lifesaver.

By getting free stuff — hotel rooms, cars, fancy clothes, kitchen appliances — a big production might trim its budget by $250k to $5m+, according to industry insiders The Hustle spoke with.

That might not sound like a lot in the context of a $65m film, but it’s money that can be reinvested into better music, special effects, or other details that improve the quality of the final cut.

Ray-Ban sunglasses were featured prominently in Top Gun(via Paramount Pictures)

Many well-known product placements in film were unpaid:

- Reese’s got star treatment in E.T. (1982) after M&Ms turned down Speilberg over fears the alien would scare kids.

- Ray-Ban didn’t pay film producers for its prominent placements in Risky Business (1983) and Top Gun (1986).

- Google not only got complimentary inclusion in The Internship (2013) but had an active say in how its brand was represented.

For the most part, these are mutually beneficial trades: Films save money on their budget, and companies get exposure and brand recognition.

But getting a product on Hollywood’s radar often requires expert help.

The connection brokers

Prop departments constantly get inundated with products hoping to fill a production team’s needs.

To stand out among the masses, brands will often hire a product placement agency like Hollywood Branded, which promises to leverage its industry connections to “make your brand a star.”

Hollywood Branded CEO Stacy Jones has placed Lacoste into Mother’s Day (2016), Vita Coco into Entourage (2004-2011), and Blackberry into Up in the Air (2009), among many others.

Two product placements in one shot: George Clooney uses a Blackberry in Up in the Air, while sporting a Hilton Hotels bathrobe (Paramount Pictures)

The process typically works like so:

- The brand pays a fee (anywhere from $40k to $300k annually, depending on the desired scope) with the agency.

- The agency “educates” Hollywood about the brand, what it can loan out, and what kinds of projects it wants to associate with.

- The agency hobnobs with decision-makers (prop masters, set decorators, transport coordinators, stylists), stays up to date with projects that are in production, and reads scripts.

- When a good fit is sourced, the agency informs the brand and secures a deal with the production company.

In brokering these deals, Jones has to ensure that the context in which a brand is used won’t cause potential conflicts for the company.

“There’s some risk involved,” she told us. “You don’t know if the film will be a hit. But you also often don’t have all the details; scripts, sets, camera angles, final cuts — everything is subject to change.”

Reebok learned this the hard way.

The brand provided $1.5m in merchandise to be featured in Jerry Maguire (1996) under the pretense that Cuba Gooding Jr.’s character, Rod Tidwell, an athlete who’d been smited by Reebok, eventually made amends with the brand.

But in the end, this scene was cut. The amended context — and a final script that included the line “Fuck Reebok!” — made the brand look like a terrible sponsor. They later sued TriStar Pictures and settled out of court.

Reebok was featured extensively in Jerry Maguire — and not necessarily in a good light (via TriStar Pictures)

Any time a brand’s logo appears in a film — even if it’s just in the background somewhere — producers have to get clearance from the company to include it.

Certain brands are hyper-vigilant about avoiding conflicts.

Eric Smallwood, president of the product placement agency Apex Marketing Group, tells The Hustle that the coffee liqueur brand Kahlúa asked to not be named in The Big Lebowski (1998) over fears that it would be associated with alcoholism. (It later embraced The Dude.)

When the film or TV show can’t get clearance, it often has to resort to less authentic workarounds like:

- Greeking, or obscuring logos: You’ll sometimes see an Apple laptop with a strategically placed sticker, or a car emblem that’s blocked by a tree.

- Generic props: Some prop companies specialize in making fictional products (like Heisler, the “Bud Light of fake beers”) that can be used in negative contexts without repercussion.

The fictional beer brand Heisler — which is often used when a film can’t get clearance from an established brand — makes an appearance in the 2001 cop drama Training Day (via Warner Bros. Pictures)

Other brands prefer to handle their product placements in-house, bypassing the middleman agencies.

Dell started doing this 20 years ago by cold-calling folks in Hollywood and organically building relationships in-house.

Gary Moore, who runs Dell’s global product placement team, tells The Hustle that the brand has been featured in dozens of TV shows and films over the years, including The Big Bang Theory (2007-2019).

In 2020, Dell made a cameo in 19 films, including 5 minutes of screen time in Bad Boys for Life that, alone, was worth ~$8.5m in ad exposure.

Whether a movie needs 100 military-grade PC desktops for an FBI scene or a dozen laptops for a startup office, he’s the go-to guy.

“We have a vetting process we look at to make sure that a show or film is a good fit for our brand,” he says. “We want to make Dell is represented in a positive light, and we turn an opportunity down if we think our products will be used in a nefarious context.”

Characters in the hit TV show The Big Bang Theory using Dell laptops (via Warner Brothers Television / CBS)

To ensure this, Moore often flies from Austin, Texas, to Hollywood just to read potential spec scripts.

“I say to every brand that comes my way, you should be doing product placement and it’s not as expensive as you think.”

But just how effective is product placement as a form of marketing?

Are film placements worth it?

Dominic Artzrouni is the founder of Concave Brand Tracking, a firm that offers detailed analytics on the performance of product placements in film.

Artzrouni provides brands like Dell with data on screen time, discernibility, logo visibility, context (location, associations), and — most importantly — the value they derive from their placements.

The process of determining this value is complex and varied, but Artzrouni says it can be simplified into a basic formula:

(Exposure on screen) x (Viewership) x (Cost of TV commercials)

It’s not an exact science, but it spits out a rough dollar amount that equates a brand’s film placement to the value it would’ve derived from traditional TV commercials.

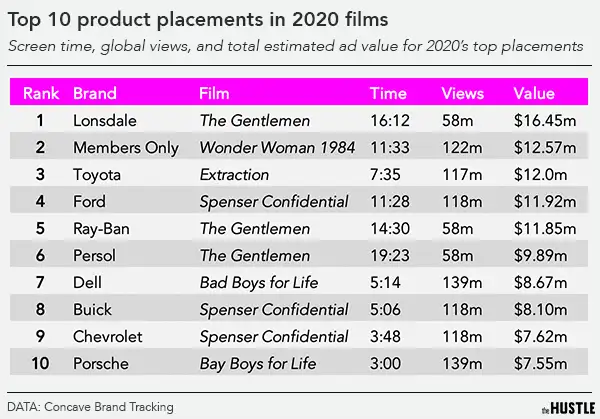

Each year, he publishes a list of the brands that derived the most value out of product placements.

In 2020, the top brand — the British clothing and shoe manufacturer Lonsdale — generated an estimated $16.5m from its 16+ minutes of screentime in The Gentlemen.

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle

Artzrouni says brands that appeared in 2020’s 50 highest-grossing films reaped $890m in combined ad value. Extrapolating across all films, he estimates that brands saw $1.2B in ad value from movie product placements in 2020.

But that only tells part of the story: Unlike traditional commercials, good films are timeless, and those values can increase exponentially.

“Product placement is the gift that keeps on giving,” he says. “The ROI can be ridiculous; a brand might get into a film for free and get $3m in value from it.”

Outside of equivalent ad value, brands can reap both short- and long-term sales benefits from placements:

- Reese’s saw a reported 65% spike in sales after E.T.

- Ray-Ban sales skyrocketed from 18k to 360k after Risky Business.

- Etch A Sketch saw sales balloon by as much as 4,500% in the wake of Toy Story (1995).

- Chevy Camaro sold 80k cars after playing a starring role in Transformers (2007), jumpstarting the ailing brand. The film was such a hit for the carmaker that it was later called a “GM ad in disguise.”

And academic research has shown that product placements can raise brand awareness by 20%, resulting in a greater recall rate, more positive attitudes, and a stronger intention of buying.

Brands are flocking to the space

Jones, of Hollywood Branded, says there has never been a better time to get into product placement in film.

“I’ve never, in 25 years, seen more opportunity in the space,” she says. “We’ve never had our phone ring more. The level and number of brands getting into the space is astonishing.”

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle (Stills via 20th Century Fox)

She attributes this to a confluence of factors:

- A changing of the ad guard: Traditional TV advertising is declining and brands are looking for creative ways to leverage digital media.

- A content boom: Streaming services have been pumping out historically high quantities of content, leading to more product placement opportunities.

- Budget awareness: Rising production costs on the backside of the pandemic have caused producers to think more deeply about ways to save money on films.

Like any form of marketing, success is often contingent on high volume and good luck.

“First you need to be lucky enough to have your product shown a lot in a film,” she says. “Then you need to get lucky with the film’s performance.”

But if Wilson Sporting Goods imparted any lesson, it’s that the potential rewards from a slam-dunk film placement are worth the risks.

More than 20 years after the release of Cast Away, the company still sells replicas of its famous blood-stained volleyball to fans all over the world.