Can technology make an experience more social instead of less so? Edwin Schlossberg’s devoted his career to that very problem.

Game designer Pete Vigeant is standing in front of a 12- by 30-foot long curved screen wearing a headset microphone and doing play-by-play commentary on a swarm of bees trying to pollinate flowers and deposit nectar back at the hive. The bees are being piloted by 30 humans in the room, split into two competing groups, who are standing in place and using hacked iPod touches as controllers. Winning requires not only deft motion controller handling, but strategic planning with your teammates who have to knock the other team’s bees off their game in order to pollinate the limited number of flowers.

Bee Racing is one of 12 collaborative and competitive bar games that its creator, ESC Games, has been testing in Buffalo Wild Wings locations for the past year. Some of the surround-sound, high-definition games are collaborative, others are competitive, and they can be played individually or in teams. This preview, part of the 2016 Fast Company Innovation Festival, included a Robot Basketball title, in which each team of 15 players tried to score baskets while moving along a roller-coaster track, and one where you play a fruit trying to collect tattoos and bring them back to your team’s base.

Edwin Schlossberg, founder of ESI Design and ESC Games.

Although it was easy to lose track of my avatar while 29 other players were zooming around the ESC Game Theater, playing alongside other people was palpably different from my experiences in VR. More than once I’ve been in a room full of players who jacked into their VR headsets and completely disappeared from one another.

This myopic, introverted experience that’s become so common in technology is something that the founder of ESI Design and ESC Games, Edwin Schlossberg, has been trying to overcome for more than three decades.

“VR is a cool tool but it’s not a social tool,” he said.

“We have tended to make our media separated so you have a visual that, in a sense, abstracts the experience,” Schlossberg continued. “There are 200,000 new people on Earth every day, we need to have experiences where you begin to really love being with other people, and gain the capability to work in teams.”

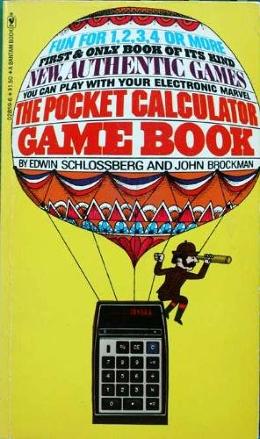

He first got turned on to the potential of video gaming by his aunt’s calculator. She was using it to balance her checkbook, and Schlossberg thought: Why spend $200 on a gadget that only does one thing? That prompted him to cowrite, in 1975, The Pocket Calculator Game Book, which was about as close to mobile gaming as you could get in that era.

The profits from that book and its sequel were used to found the experience and interaction design firm ESI Design. Two years later, the firm created The Learning Environment at the Brooklyn Children’s Museum, a participatory installation that became a trendsetter for children’s museums around the globe.

The sight masks at Macomber farm, which help visitors empathize with animals by seeing the world from their perspective.

The seeds of that project sprouted into various forms across Schlossberg’s retail, architectural, and and brand experience work through the decades. In 1983, his installation for the Massachusetts Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals at Macomber Farm included several “sight masks,” essentially oversized, proto-VR headsets that allow you to see through the eyes of different animals (and learn, for example, why horses keep their heads down in order to see).

Throughout the 1980s, ESI created location-based entertainment experiences, including in nightclub-like settings such as the IPL Pavilion.

Perhaps the most famous incarnation of the firm’s approach can be seen in Boston’s Edward M. Kennedy Institute for the U.S. Senate, where there’s a full-scale, interactive simulation of being a senator. Up to 100 people get to wheel and deal other participants into voting for their bill over the course of two-and-a-half hours. You are scored on how many people vote for your proposal. The technology—tablet computers and large screen displays—enhance the experience without replacing the necessity of person-to-person communication and working out their differences.

“That’s the heart of the society we love,” said Schlossberg, “which is that we’re in it together and see the consequences of our actions.”

The ESC games rely on the same underlying philosophy about experience design, but harken back to those multiplayer, location-based entertainment experiences of the 1980s. The technology is vastly improved, of course, which allowed Schlossberg to overcome many of the problems with his earlier versions of the same ideas.

“The secret sauce is the back-end communication and the networking,” says Vigeant, ESC’s Director of Platform and Game Development (and the game announcer for our demo). Overcoming network speed and latency was the key—when a player tilts the controller, the on-screen feedback has to be in real time, otherwise the whole game falls apart.

Two design patents and five utility patents related to the ESC Game Theater are still pending, and they cover the lighting cues, a system for accelerated Wi-Fi communication, and the game controller—those hacked iPod touch screens were also an essential piece of gear that only became affordable enough to deploy at scale in the last few years.

Another key component is the Unity game engine, which allows ESI to not only develop the gameplay, but display the games on the 3350 x 1200 pixel screen and control the lights in the room as well.

ESI’s staff includes architects, who design the physical experience. “We’ve found that the coherence and effectiveness of physical and digital experience requires a group of people who work well together,” says Schlossberg.

This particular demo wasn’t the ideal test of collaborative gaming as social lubricant, since it kicked off at 9:30 in the morning. But it was easy to see how, in a setting like the Garden State Mall in New Jersey, where the installation will debut in a couple weeks, you might want to peel off and grab a beer with a co-player after a few rounds. ESC is already planning to host contests, as well as competitions that they hope will lead to larger scale leagues and tournaments.

A couple of the titles being prepared for the launch were produced in partnership with Warner Bros. The first is Astro Beams, from the Montreal studio Sarbakan, which is known for the upright arcade version of Candy Crush you may have played at Dave & Busters. And the most anticipated isPixel Prison Blues, which is made by BumbleBear Games, creators of the indie hit Killer Queen Arcade.

But Schlossberg, 71, says these games are “like Pong in the history of this environment.” he says. These are still early days for understanding how to make a coherent physical and digital experience that enhances socialization by getting the technology out of the way. He’s bullish on the potential of augmented reality, which he says is “spectacular as a social experience.” ESI is also exploring dynamic data visualizations that can be embedded into the physical world, as well as digital-physical massively multiplayer games.

“Now, when you walk into a store, if all the images around you are still you think the store is dead,” he says. “Our eyes have changed. We need to see things moving and dynamic—and we need to see ourselves in the images.”

This article first appeared in www.fastcodesign.com

[Photos: courtesy of ESI Design]

Seeking to build and grow your brand using the force of consumer insight, strategic foresight, creative disruption and technology prowess? Talk to us at +9714 3867728 or mail: info@groupisd.com or visit www.groupisd.com