For decades, fashion brands have built their businesses on convincing customers to buy new clothes, racking up profits with each new purchase. But in new twist, fashion brands are persuading their customers to wear clothes they already own. Some are even paying them to do so.

Take fashion label Aday. To kick off the New Year, it invited 600 customers to wear outfits they’ve already purchased from the brand and will pay them between $25 and $75 in credit depending on how many times they wear it. Wool&Prince issued an even more dramatic challenge: If customers wear the same dress or button-down shirt for a 100 days straight, they’ll receive a $100 gift card. Across the pond, menswear brand L’Estrange London challenged customers to repeatedly wear the seven items in its core collection for the chance to win back the cost of all the garments.

Clothes are destroying the planet: Every year, fashion is responsible for 10% of carbon emissions, swallowing up 93 billion cubic meters of water and spewing half a million tons of plastic microfibers into the ocean. Fashion’s enormous environmental footprint comes down to the sheer volume of clothes it churns out. More than 100 billion garments are made every year—for just eight billion people. While some brands are trying to become more sustainable by using eco-friendly materials like recycled plastic and organic cotton, experts say that this is unlikely to move the needle if the industry continues overproducing. “We’re all for recycled and natural materials,” says Mac Bishop, founder of Wool&Prince. “But we feel that the most important thing that is not being addressed is reducing consumption.”That’s precisely why brands like his are focused on normalizing owning fewer garments, and wearing them on repeat. Of course, this is also a clever marketing strategy, since they want you to wear their garments rather than any old clothes in the closet. But the timing is right: After months of being stuck at home wearing the same comfy basics day after day, many of us have seen the benefits of outfit repeating.

CHANGING CONSUMER BEHAVIOR

Having an overstuffed closet is a relatively recent phenomenon. A few generations ago, clothes were precious because fabrics were expensive and garments were time-consuming to make. Then in the 1990s, brands like H&M and Zara found ways to make cheap, trendy clothes by using low-quality materials like polyester and creating global supply chains that relied on poorly paid workers in developing countries. The rest of the fashion industry followed suit, with every company from Target to Old Navy making clothes so cheap they are basically disposable. One study found that many consumers wear a garment only seven times before throwing it away. This is good for fashion businesses; since they sell their clothes at low prices with small margins, they need to sell a large volume to make money.

Brenna Davis, Aday’s head of marketing, says that launching the outfit repeater challenge was a way to help consumers rethink their relationship to clothing after years of being conditioned by the fast fashion mindset. But the key to making it work was to illustrate that owning less can actually be fun and liberating. “We wanted to show that if you have clothes that you really love and that can be worn in different ways, you don’t really need to own as much,” she says.

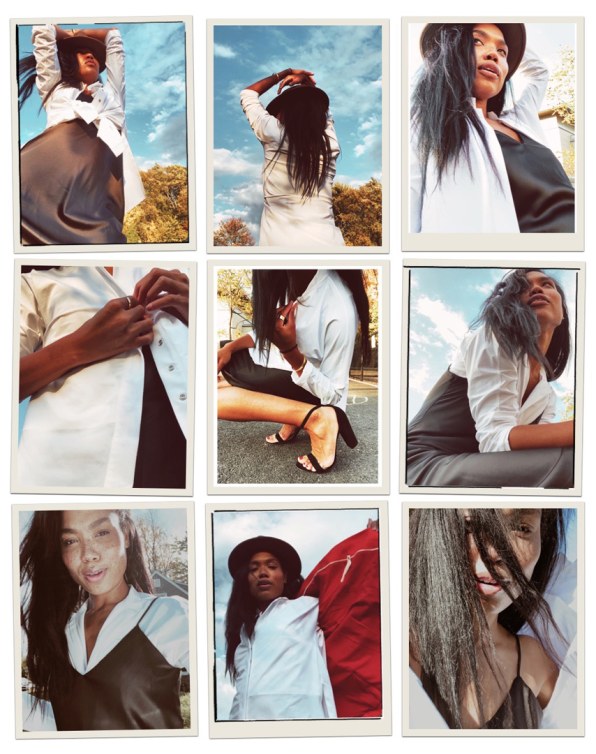

In October, Aday did a 100-person version of the challenge, as a kind of pilot program. They surveyed customers before and after, and found that many enjoyed spending less time getting ready in the morning: It took far less time to accessorize a look with a scarf, jewelry, or cardigan than building an entire outfit from scratch. Others loved that getting more use out of a single garment was a way to reduce that garment’s impact on the planet.

Wool&Prince’s Bishop says that another way to change consumer behavior is to design clothes from the outset to be worn repeatedly. While many fashion brands design to the latest trends, focusing on new color palettes and silhouettes, Wool&Prince takes the opposite approach. The brand’s designers identify the most neutral colors, then create simple classic silhouettes. Dozens of women have successfully completed the 100-day challenge wearing the Wool&’s Rowena Swing Dress, a long-sleeve, knee-length, A-line dress that comes in black, navy, burgundy, and gray. It can be dressed up or down, worn in different climates, and easily accessorized.

SELLING LESS CAN BE PROFITABLE

To many fashion companies, the idea of selling fewer, more durable clothes seems like bad business. But Nina Faulhaber, Aday’s co-founder and co-CEO, believes that it is possible to be profitable even though you’re selling a limited number of goods. She points to brands like Patagonia, which offers free repair services so customers can wear existing clothes for longer. Or luxury brands that sell well-made goods at a markup.

Faulhaber doesn’t think that sustainable clothes have to be sold at luxury prices, but brands like hers need decent margins to be sustainable. At both Aday and Wool&Prince, the average price of a garment is a little under $150, which is far more expensive than fast fashion, but significantly cheaper than luxury brands. “We need margin to be able to source long-lasting fabrics, and to pay our workers adequately,” she says. “But I believe it’s important to show the customer that they can get more value from our clothes than from fast fashion.”

Brands encouraging customers to wear their clothes repeatedly are also making a financial argument to them. Fast fashion brands have taught consumers to pay attention to the ticket price of an item, but if they only wear the item a few times because it is poorly made or will go out of style, the cost per wear is expensive. For example, if you buy a polyester sundress for $28 and wear it seven times, it costs $4 a wear. Meanwhile, the average cost of an Aday garment is $145, and customers report that they wear it once a week. Since the clothes are designed to last at least five years, that’s $0.52 a wear. Aday’s challenge was carefully designed to illustrate the value of wearing clothes on repeat, since participants earn $0.52 each time they wear the item. “We’re trying to show that this approach can be a win-win,” says Faulhaber. “The customer gets good value, and the brand still makes money.”

The waitlist to join Aday’s challenge has more than 4,000 people on it, and the brand hopes to offer more challenges after this one is over. But can brands like Aday and Wool&Prince impact the fashion industry more broadly? It’s an uphill challenge, but there are signs of progress. For instance, H&M’s venture capital wing invested in Aday’s $2 million seed round. Helena Helmersson, H&M’s CEO, visited Aday headquarters to learn more about its business model. Says Faulhaber: “I think there’s an awareness that fast fashion may not be around forever, and brands need to start thinking about other ways to structure a fashion company.”

This article first appeared in www.fastcompany.com