Imagine this: You’re marching toward a protest when a police van rolls up. There are whispers that the mayor has chosen to crack down on public dissension, and you’re worried that your peaceful demonstration could be misconstrued as something else. If it is, your face will be captured by a random camera, recognized, and filed as a problematic citizen—perhaps it will even get you arrested.

“The ring almost acts as the keys to engage (or not) with society, to whatever degree you’re comfortable,” says Jenny Clark, associate creative director at Argodesign, who created the hardware mockup. Note that the device is a concept that’s not actually being built, and the software infrastructure to support it would be immense—requiring buy-in from the government and private companies alike.That said, the Me.Ring feels feasible because it’s a fairly typical smart device. It’s a gadget with simple controls (literally, one switch) that uses an app for far more nuanced controls (much like a Phillips Hue light bulb or a Fitbit). In this case, the Me.Ring app would allow you to have settings for sharing things such as your contact data with professional networks, and your medical data with health practitioners. The switch would activate a collection of those preferences, customized to you.

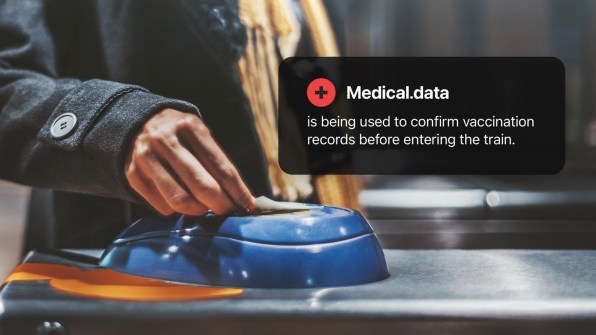

It’s actually pretty easy to imagine how the Me.Ring might work on the technical end. Bluetooth and other low-power wireless protocols could communicate, not just with your phone, but with beacons in your environment such as smart turnstiles, sidewalks, cameras, and digital signs. Cities are installing many such sensors already. However, the device isn’t just tracking your steps or alerting you that you have a new email; it’s serving as your liaison and data broker to an invisible world of data trackers.

To do so, the ring could send signals, like mini digital contracts, to these points of access. It would clarify whether your data was collectible, which parts of your data were collectible, and for what purpose. Then, for private-sector entities interested in using or collecting your data, Jared Ficklin, chief technologist and partner at Argodesign, suggests companies could send you offers. If a beacon noticed you were eating at McDonald’s, perhaps a restaurant analyst company could ask to record the next 10 places you went out to eat for a small payment or coupon.

Because sometimes, there actually are benefits to having your data shared! It’s helpful for cities to understand how many people walk on a certain block every day, so they know where to invest in infrastructure. It’s helpful for a store to know your shopping history so it can make future suggestions. And Ficklin—a highly optimistic capitalist—suggests that there are all sorts of untapped possibilities once our data is something that we can barter, rather than something we sign away in perpetuity each time we go online or step into public.

That’s why the Me.Ring actually seems more out of reach in terms of the necessary laws than the necessary technologies. The government would need to introduce a whole scaffolding of policies on the collection and ownership of personal data, and thus far, the U.S. has failed to regulate private companies with any serious baseline of consumer protections.

“We’re taking baby steps toward this [data marketplace]. . . . With Europe’s [GDPR], they said you as the user get to choose what data is recorded,” says Ficklin, noting how just about every website now pops up a box asking which tracking cookies it can save. “99% of people say ‘whatever.’ 1% open it and check one option at a time.”

Indeed, if Argodesign’s example of hiring a service to track your face and find where you left your coat sounds extreme, just realize that the LAPD requested footage from camera-loaded Ring doorbells to identify Black Lives Matter protesters in 2020. These powerful data-combing capabilities already exist; consumers are simply completely not in control of them. And if Me.Ring makes anything clear, it’s that the world of data collection and marketing is broken. If our very privacy can exist again, this world needs to be fixed.

“We’re industrial and product designers—we like to jump to the end,” says Ficklin of how the Me.Ring concept fits into the current culture of surveillance. “Maybe we want it to come as much as we see it coming.”