Affectiva’s emotion-sensing technology now helps game developers personalize games to the player’s mood.

Game developers have always been interested in how players might react to the characters and plots they created—but what if they could tell exactly how the player was feeling and tailor the game to their mood?

“Back in the olden days we had to do a lot of guesswork as game designers,” says Erin Reynolds, the creative director of the gaming company Flying Mollusk. “Is the player enjoying this? Is the player bored? You had to create a game that was one size fits all.”

Erin Reynolds

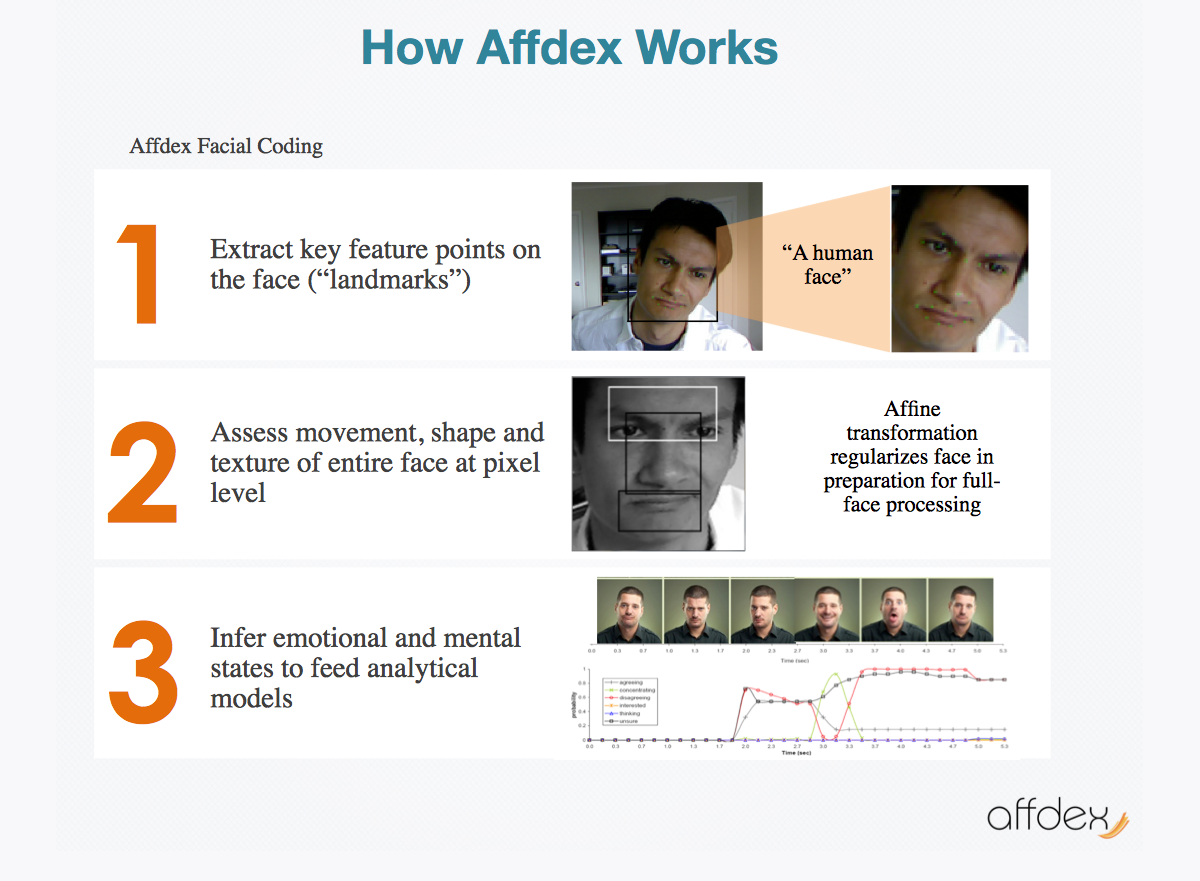

But all that is changing fast. Affectiva, an MIT Media Lab spin-off that creates technology that recognizes people’s emotions by analyzing subtle facial movements, has created a plugin that game developers can integrate into their games to make them more emotion-aware. This marks Affectiva’s first foray into the gaming space; the technology is also used in other industries better understand how people react to advertising and political polling, among other things. The plugin will be available on Unity, a game development platform used by over 4.5 million developers. In practice, it means that video games can now read a player’s face through a standard webcam.

“Most games have emotions as a core part of the experience,” says Rana el Kaliouby, Affectiva’s cofounder and chief science officer. “We’ve made it possible to easily build an emotional response into the game dynamic.”

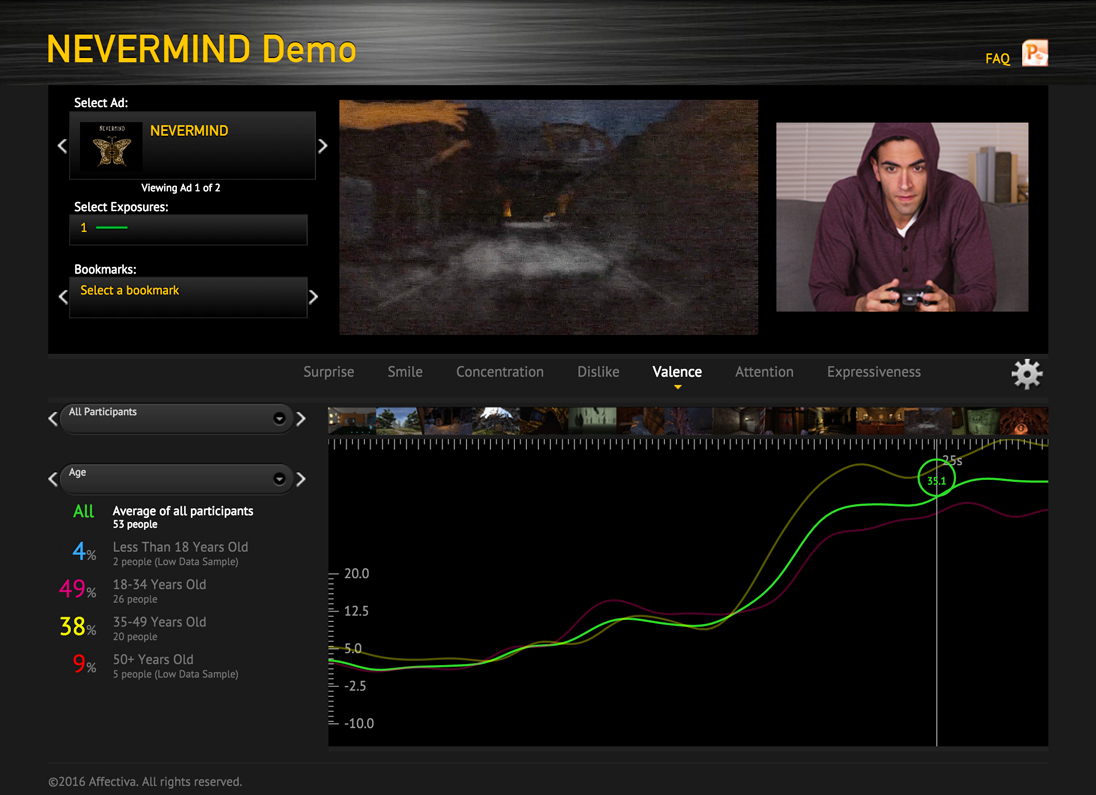

Reynolds saw the benefits of the technology immediately and has already integrated it into Nevermind, her psychological thriller game. “Games are capable of evoking very specific and complicated emotions,” Reynolds says. “To have the ability to respond to those emotions really opens up a lot of options to game creators. We can have a two-way conversation with the player.”

In the dark, scary world of Nevermind, the player is in a ward in a mental hospital where the goal is unlocking terrifying repressed memories in each patient’s past to help them work through their trauma. People who enjoy playing the game get a kick out of feeling fear and like the challenge of managing their anxiety. Using technology from Affectiva, the game can now sense how the player is feeling, and adjust the difficulty based on fear level. “The idea behind the game is to make people more mindful of those subtle signals of stress and anxiety within themselves,” Reynolds explains. “If the player wants to progress through the game, they must be conscious of the tightness in their stomach or the fact that they are starting to feel tense.”

Still from Nevermind

Of course, how a game interacts with the player’s emotions depends a lot on its context or theme. On the opposite end of the spectrum from Nevermind, children’s games can teach kids to regulate their emotions better, by helping them work through frustration, anger, or anxiety. And more generally, games can use a player’s emotions to move the plot along. If a player is trying to break into a castle, for instance, they could charm the guard with the smile, or intimidate him with an aggressive face.

Gabi Zijderveld, Affectiva’s head of product strategy, explains that apart from altering game play, Affectiva’s technology can also provide plenty of real-time data about how interested the players are at each point in the game. “Games today don’t measure the emotional impact they have on players,” she says. “By creating games that are more engaging, developers can increase their bottom line, because it keeps people coming back to the game.”