STOREHOUSE, A MOBILE PUBLISHING NETWORK BY AN EX-APPLE DESIGNER, HAS DECIDED THAT FOLLOWERS CREATE PANDERING, AND PANDERING RUINS EVERYTHING.

When the iPad app Storehouse launched in early 2014—designed as a way to publish brief, uniquely laid out, photo-driven stories with the world—it operated with all of the flourish you’d expect an app led by an ex-Apple designer to have. The company was founded by Mark Kawano, who had worked on iPhoto and served as Apple’s user experience evangelist before founding his company, and it showed.

I gushed over the smallest UX touches of the initial product—though criticized its lack of obvious social features (there was a generalized news feed, but no hashtags or followers). Predictably, their next versions included these social network mainstays, and Storehouse’s sharing core became more or less like that of every other social network out there.

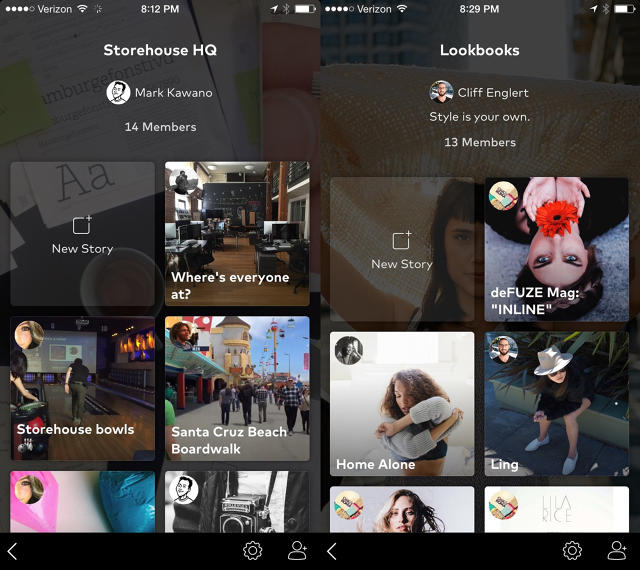

But with Storehouse 2.0—out today for iOS—Kawano is doing an about-face. The new app has no feed. It has no followers. And it has no hashtags. Everything about discoverability and sharing has been removed. Instead, each story you create is private by nature. You can text and email it to friends. Or you can place it in a shared “space,” where you can drop in stories for a small group of friends to follow.

Why the change? “Like a lot of social networks, people started sharing to get likes, to get follows, to get suggestions,” Kawano says, “rather than why we intended it, to create these stories.”

You can edit stories for yourself, particular friends, or members of your family. Then if you want to, you can still blast a story out over Facebook and Twitter, but Storehouse itself won’t promote these wide-net social plays inside its own product, enabling you to become the sort of brute-force celebrities we see on Instagram, Vine, and Twitter.

“By removing the follow model, it’s much more a product that reflects the way people normally interact with each other,” Kawano says. “[Previously on] Storehouse, someone would go out, take a whole bunch of beautiful photos on vacation, share them, get discovered, and get a whole bunch of followers. Which is great for that person! But then, they’d have this other thing they want to share, and they have a whole bunch of followers they know are interested in beautiful vacation photos. And they’re like, ‘Well, do I post this? It’s personal.’ Or, ‘This is a weird story. It’s going to show a much more creative side.'”

What Kawano is referring to is an odd, possibly underexplained social network phenomenon. A lot of us pander to the crowd—and Storehouse had no shortage of that. But the motivations weren’t quite as simple as eliminating cheesy self-promoters. A platform like Facebook contains family, friends, and acquaintances. We tend to look at these social circles mainly as levels of privacy, asking, who is close enough to see photos of our children or hear news of losses in our family? But privacy is only one aspect of how humans interact. When we walk into the office on Monday, we don’t just yell out to everyone that we made a steak the night before—we ask ourselves, who’d actually be interested in what I made for dinner? And then we corner them in a cubical while waxing about the merits of artfully prepared ribeye.

“The reality is, you look at your camera roll, and the things that are in there [prove]people are multidimensional, and you don’t have a single set of frames that match up with [everyone else’s tastes],” Kawano says. Storehouse 2.0 wants to support these aspects of your personality across your social sphere. “I’ll share the food photos with friends I know will appreciate the food stuff, and photos with my kids, I’ll share that with family and friends who care about my kids.”

When I ask Kawano if poor subscriber trajectories may have accounted for this sudden pivot, he insists that Storehouse had great engagement numbers that “most companies at our stage would love to have.” Rather, people weren’t using the product in the way it was originally intended, he says: to tell authentic stories, rather than stories destined to go viral.